Module 1: “That Chinese Girl”

Can one family’s assertion of their civil rights become a “victory” for an entire community?

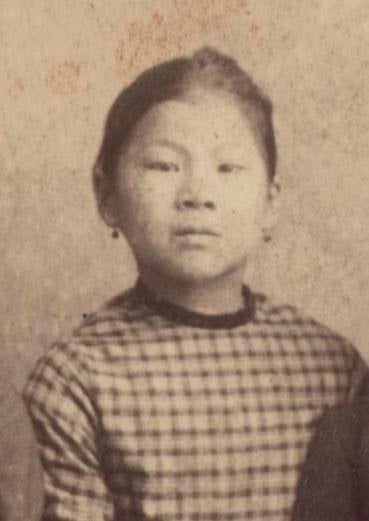

On a warm autumn day in September 1884, Mary Tape dressed her daughter Mamie in a checkered dress, tied a ribbon in her braid, and took her to the Spring Valley Primary School on Union Street, in the Cow Hollow neighborhood of San Francisco, California. When they arrived, the principal, Jennie Hurley, refused to admit Mamie to the school.

Although it was not obvious from their names, the Tapes were Chinese, and the San Francisco Board of Education did not allow Chinese children into its schools. Although Mary Tape knew this, she thought being Chinese would not matter because the family spoke English and lived in a white neighborhood.

This module is about the Tape family, San Francisco’s public education system in the nineteenth century, and the family’s landmark California Supreme Court case. Other modules will also spotlight different members of the Tape family and the many ways they claimed their identities in the United States.

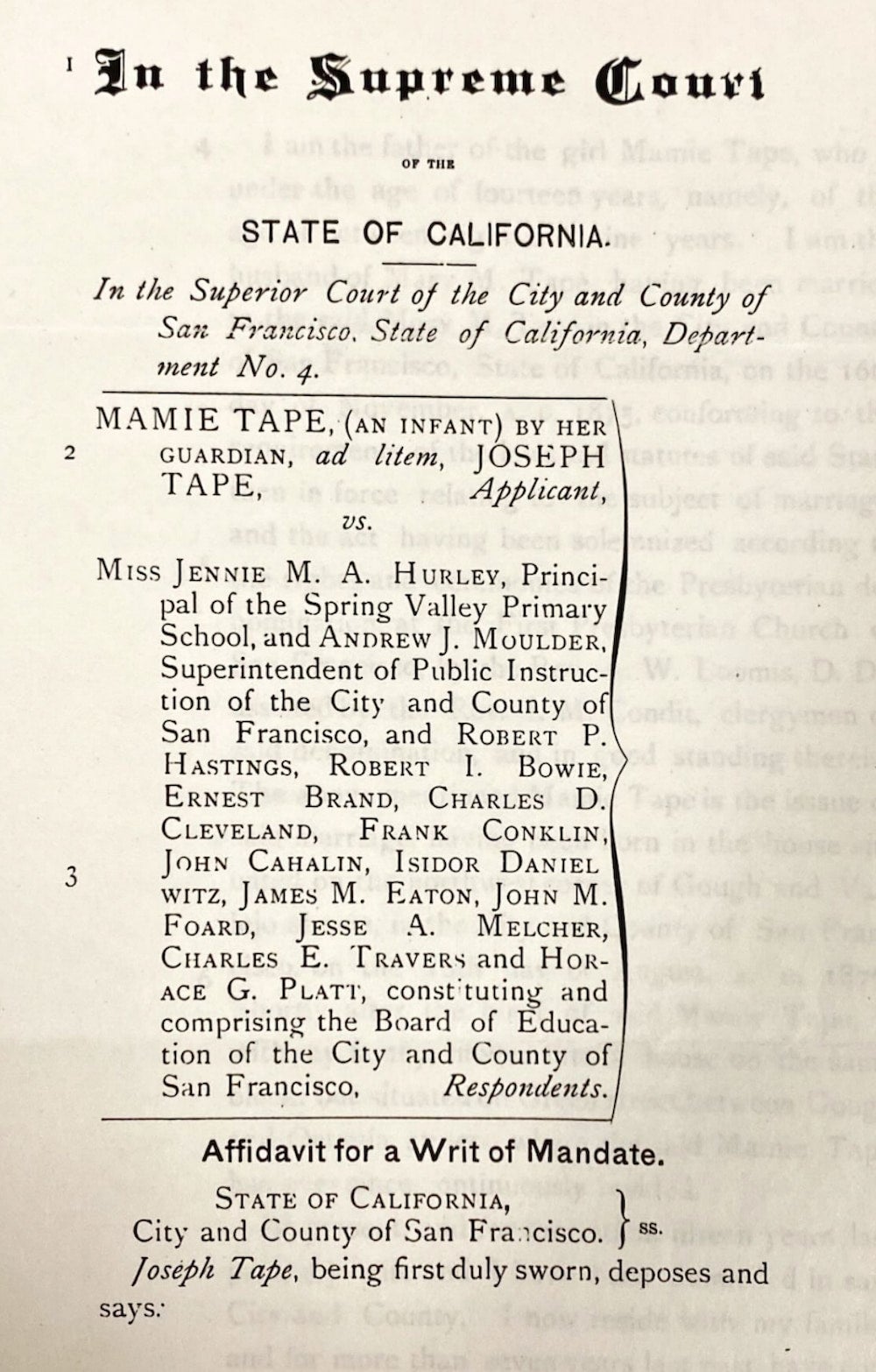

Text 37.01.02 — California Supreme Court affidavit for Tape v. Hurley.

Courtesy of Mae Ngai. Metadata ↗

How was the Tape family viewed in comparison to the rest of the Chinese immigrant community, and how did this lend them to be ideal figures in fighting for school inclusion for Chinese Americans?

What arguments did the Tape family use to fight for Mamie Tape’s right to go to school?

What were the limitations of the “victory” in Tape v. Hurley?

Education and San Francisco’s Chinese Community

In the nineteenth century, California’s laws on public education initially excluded marginalized racial groups from public schools, including Black, Native American, and Asian students—whom people at the time commonly referred to as “Negroes, Indians, and Mongolians.” 1 (Note that these are outdated and offensive terms for racial categories that are no longer used today.) Later, the state allowed for segregated schools—separate schools for white students and non-white students.

Chinese families in San Francisco, however, found that even a separate school was hard to come by. From 1859 to 1871, they had only sporadic access to public education, despite ongoing appeals to the school board by both Chinese community leaders and white Protestant missionaries. They argued that the Chinese paid taxes and that their exclusion from tax-supported schools was a form of taxation without representation.

The first San Francisco school for Chinese students started in 1853. It was not a public school, instead funded by Chinese merchant leaders and Christian missionaries. It offered English-language instruction for some twenty Chinese boys and men in a small room on Sacramento Street. Missionaries believed that teaching English would help promote Christian conversion. A reporter who visited the school wrote that the students showed “eagerness to become acquainted with our language, manners, and customs.” 2

In 1857 the San Francisco Board of Education agreed to provide the Chinese with English-language instruction, funding a teacher for a single class held in the “gloomy basement” of the Presbyterian mission in Chinatown, and taught students primarily through Bible reading. The teacher reported that “the little Celestials were very apt at learning.” 3

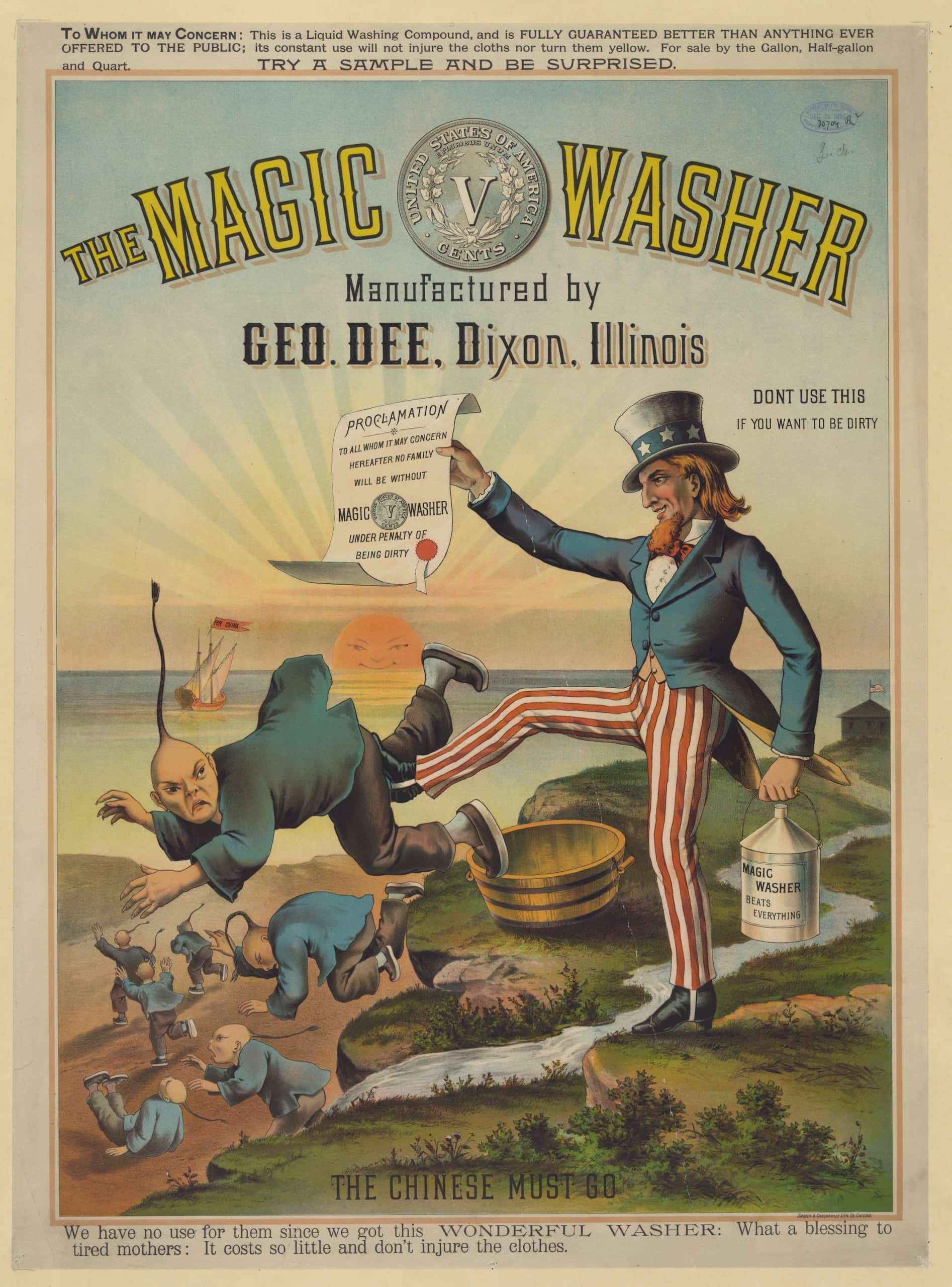

San Francisco’s Anti-Chinese Movement

Public education was thus one of the first casualties of the anti-Chinese movement in San Francisco. In 1871 the Board of Education terminated support for the Chinatown school, noting that the state’s 1870 law required separate schools for “children of African descent, and Indian children.” 5 While the law made no mention of the Chinese, the board interpreted it to mean they had no responsibility to educate Chinese children. Throughout the 1870s, the board ignored or dismissed individual and group petitions by Chinese communities seeking their children’s admission to public schools. By then there were three thousand Chinese children in California, two-thirds of them in San Francisco. Education was no longer just the concern of only young adults in the mercantile business.

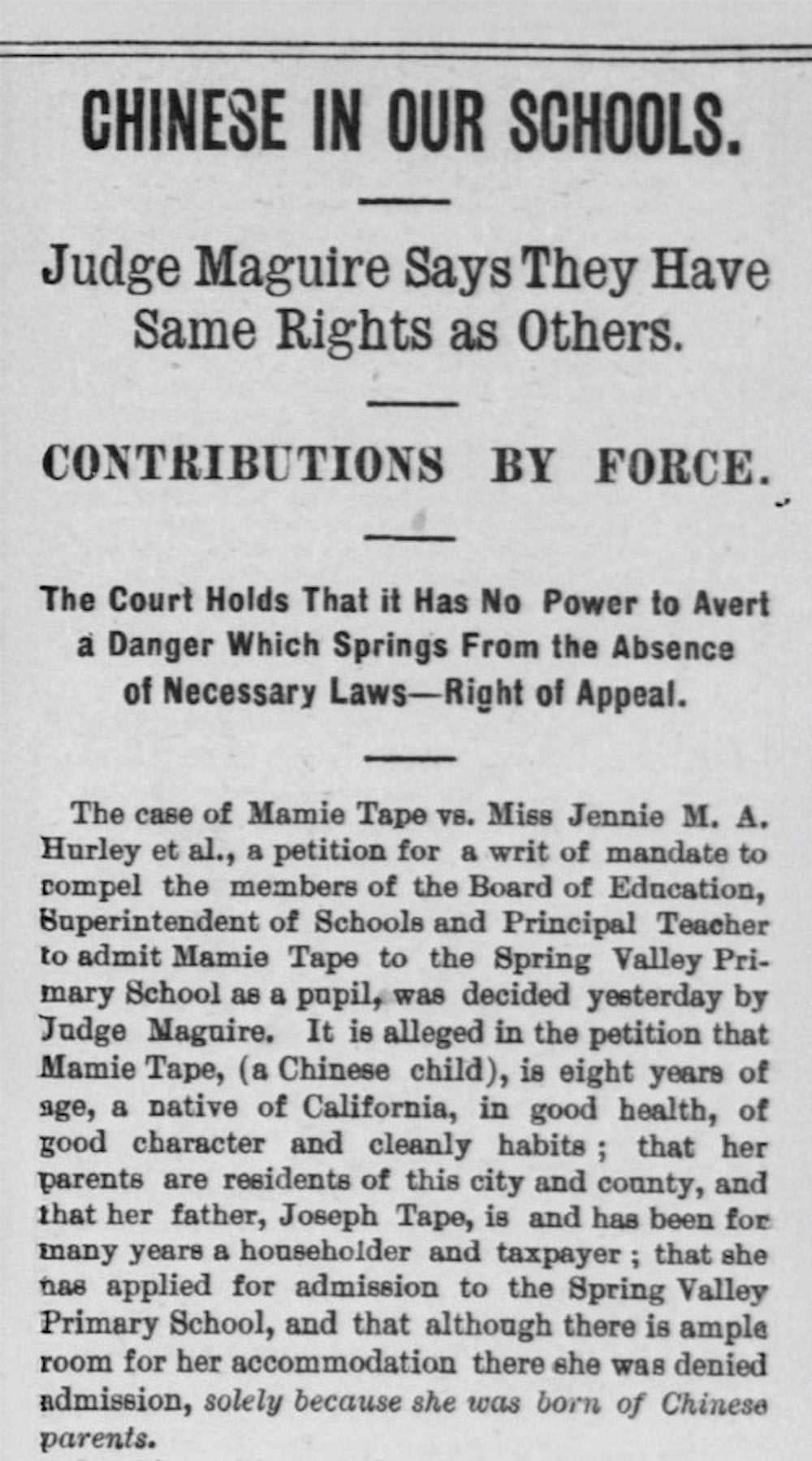

In 1880, California passed a new school law that entitled all children in the state to public education. But San Francisco continued to ignore Chinese requests for schooling—until Mamie Tape went to court.

Mamie’s father, Joseph Tape, was a drayman who serviced Chinatown’s merchants by hauling their goods in a horse-drawn wagon. He had come to America at the age of fourteen and worked first as a servant for a white family before starting his own business. When Joseph brought his complaint to the school board, it sparked some debate, but the board voted 8–3 to “absolutely prohibit … each and every principal of each and every public school” from admitting any Asian child. 6

Taking the Case to Court

Joseph Tape retained a lawyer, William Gibson, to sue the San Francisco Board of Education and Principal Hurley on Mamie’s behalf. Gibson was the son of a Methodist missionary and Chinese community advocate, Otis Gibson. William was born in China and later graduated from Harvard Law School.

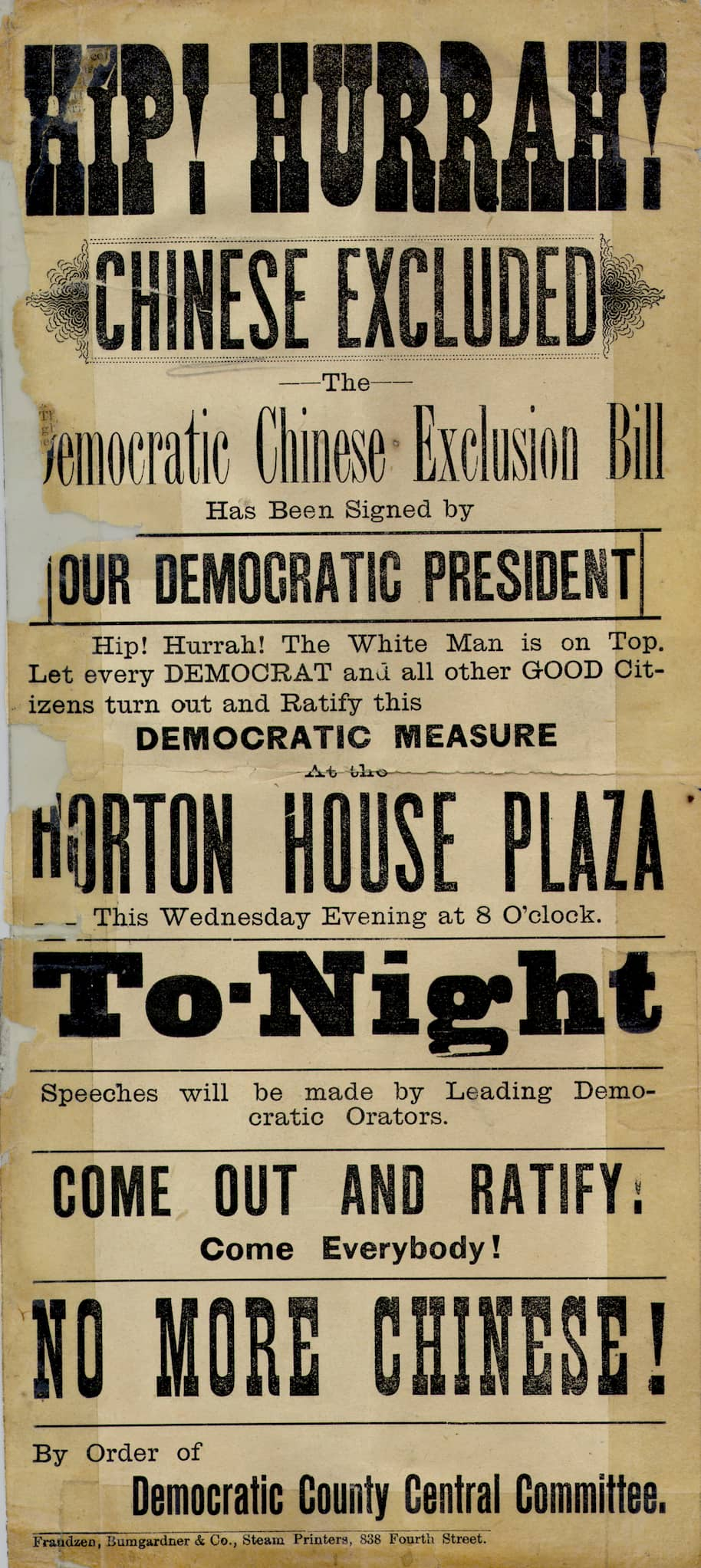

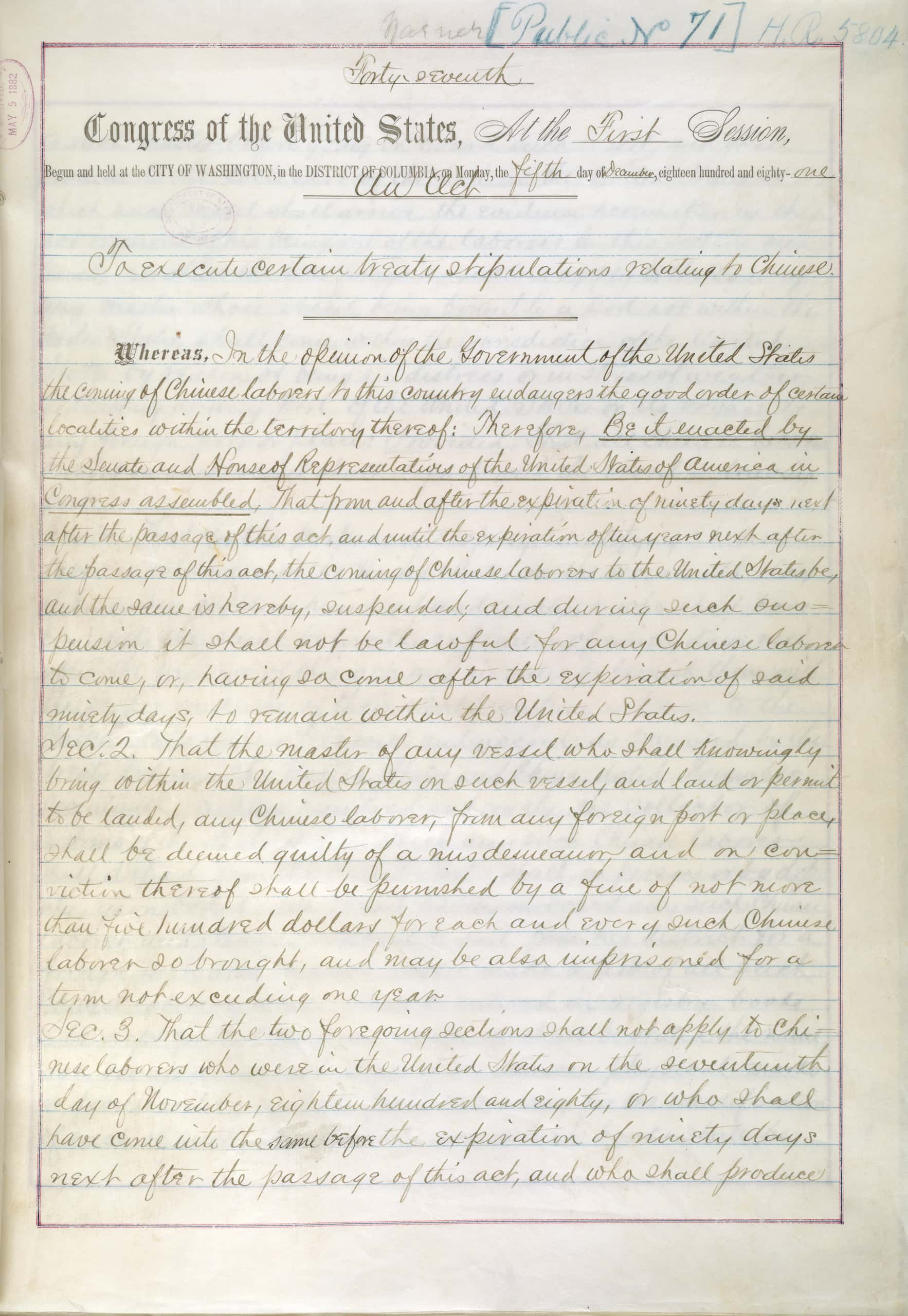

The Tape v. Hurley case had a high profile in the local press. By late 1884, the San Francisco Evening Bulletin reported updates to the story with the simple headline, “That Chinese Girl.” The Tapes’ lawsuit was extraordinary at the time because it was made on the heels of the Chinese Exclusion Act, passed in 1882—the result of decades of racist, anti-Chinese agitation. The Exclusion Act barred all Chinese laborers from entering the United States and all Chinese from acquiring naturalized citizenship. Between 1882 and 1902, Congress passed additional laws that further restricted Chinese immigration.

Text 37.01.04 — Poster “Hip! Hurrah! Chinese Excluded” by the Democratic County Central Committee celebrates the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Courtey of the Royal BC Museum. Metadata ↗

Text 37.01.05 — The Exclusion Act (May 6, 1882) banned entry of Chinese migrant laborers into the United States. It was the first piece of significant legislation restricting migration into the United States and set precedent for the country’s ongoing discriminatory immigration policies.

Courtesy of the National Archives Catalog. Metadata ↗

Although courts blocked Chinese immigration until the Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, the Tape case was not about immigrants, but instead about an American-born Chinese who was a US citizen. Despite ongoing hostility toward Chinese immigrants, there were some white people, like school board member Charles Cleveland, who believed that under the Constitution all children born in the United States were citizens. According to Cleveland, “If Chinese may sometime be allowed to vote, they certainly ought to be educated.” 7

Segregation, not Inclusion

Anticipating this eventuality, the school board had rushed an act through the state legislature authorizing separate schools for “children of Chinese and Mongolian descent.” 9 It prepared to open a Chinese Primary School on the edge of Chinatown, on Jackson Street, near Powell Street, above a grocery store.

The Tapes however did not want to send their children to a school in Chinatown. They did not live in or near Chinatown, and wanted their children to be raised as Americans, not as Chinese. On April 7, 1885, before the Chinese Primary School opened, Mamie returned to Spring Valley Primary School along with her parents and two lawyers. But Principal Hurley was prepared—instead of excluding Mamie directly, she threw obstacles in Mamie’s way, claiming that the child did not have the proper vaccination papers and that the class was overenrolled.

Mamie’s mother, Mary Tape, wrote a letter to the San Francisco Board of Education, which was printed in the Daily Alta California. She assailed the adults who persecuted an eight-year-old child just because of her Chinese descent:

“Dear sirs, … Will you please to tell me! Is it a disgrace to born a Chinese? Didn’t God make us all!!! … Do you call that a Christian act to compel my little children to go so far to a school that is made in purpose for them. My children don’t dress like the other Chinese. … Her playmates is all Caucasians ever since she could toddle around. If she is good enough to play with them! Then is she not good enough to be in the same room and study with them? … It seems no matter how a Chinese may live and dress so long as you know they Chinese. Then they are hated as one. There is not any right or justice for them.” 10

She ended the letter vowing, “Mamie Tape will never attend any of the Chinese schools of your making! Never!!!”

Image 37.01.09 — Photo of Chinese primary school students in San Francisco, circa 1890. Mamie is in the center of the second row, and Frank is to her right. Photograph by Isaiah Taber.

Princeton University Press, 2010. Metadata ↗

Mamie and her brother Frank were, however, the first students to arrive at the Chinese Primary School when it opened on April 13, 1885, five days after Mary wrote the letter. A reporter remarked upon the Tape children’s “neat appearance” in American-style clothing. 11 Four other boy students, in queues and Chinese-style clothes, had previously attended mission schools and could all read and write English. Although Mamie and Frank were also fluent in English, they had never been to an actual school. While the other children followed the teacher’s instructions, the Tape siblings did not, and instead ran around the classroom in a “frolic.” Still, the reporter said that Mamie was the “most intelligent member of the class.”

Within a few years the Chinese Primary School had one hundred students. Mamie was the only girl. In 1890 she and Frank dressed up in Chinese costumes to sit for a school portrait—fancy silks that showed their parents’ wealth that contrasted with the plain cotton tunics worn by the children of laborers. But all that was just for show. Mamie and Frank were “American” in terms of their clothing, English fluency, residency in a white neighborhood, and white friends. But they were also Chinese, in physical appearance and according to the social practices and policies that segregated them. These factors impeded their full entry into the mainstream of American society. Mary Tape had sworn that her children would “Never!!!” attend the segregated Chinese school, but the family conceded. There was no other option if the Tapes wanted their children to receive an American education.

Tape v. Hurley established that Chinese American citizens could not be excluded from public schools. But rather than achieving full inclusion in the school system, the ruling led to legal segregation. This made Chinese Americans second-class citizens, similar to the experiences of African Americans under Jim Crow laws that created separate schools, train cars, building entrances, and public toilets across the South. Though anti-Chinese laws in California and the West were not as extreme as those in the South, Chinese Americans still faced many racial barriers.

Glossary terms in this module

Chinese Exclusion Act Where it’s used

Considered the first significant piece of legislation to restrict immigration into the United States, this federal law prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers for ten years.

civil rights Where it’s used

Legally protected rights that guarantee equal social opportunities and protection under the law for all citizens.

due process Where it’s used

The principle that all people should be treated equally and fairly by the justice system; in the United States, this right is protected by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

exclusion Where it’s used

The policy and/or practice of banning or prohibiting a person or group of people from accessing a place, group, or resource.

naturalized Where it’s used

A person born outside of the country who gets citizenship as an adult.

queue Where it’s used

A hairstyle originally worn by the Jurchen and Manchu people of Manchuria, the Qing dynasty required male subjects to wear queues; the style’s association with China meant wearers were often discriminated against and targeted by perpetrators of anti-Chinese violence in the United States and Australia.

respectability Where it’s used

The quality of being socially accepted as proper or correct, and therefore worthy of being respected. The norms or behaviors considered respectable in a society are usually determined by its dominant culture.

segregation Where it’s used

The system and/or act of separating a group of people from others based on race, ethnicity, or other identity categories.

Tape v. Hurley Where it’s used

A California Supreme Court case that ruled California could not exclude Chinese children but allowed for the creation of segregated schools.

Endnotes

1 “School for the Chinese,” Daily Alta California (San Francisco, CA), January 9, 1853.

2 Victor Low, Unimpressible Race (East/West Publishers, 1982), 23; Charles Wollenberg, All Deliberate Speed (University of California Press, 1972), 32.

3 Daily Morning Call, editorial, March 7, 1878.

4 Daily Morning Call, editorial, March 7, 1878.

5 Daily Morning Call, editorial, March 7, 1878.

6 “The School Board,” San Francisco Evening Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), October 22, 1884; “School Contracts,” Daily Alta California (San Francisco, CA), July 6, 1884.

7 “The School Board,” San Francisco Evening Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), October 22, 1884.

8 Affidavit for Writ of Mandate, Mamie Tape/Joseph Tape v. Jennie Hurley et al (Superior Court of San Francisco 1884).

9 “Chinese Mother’s Letter,” Daily Alta California (San Francisco, CA), April 16, 1885.

10 “Chinese Mother’s Letter,” Daily Alta California (San Francisco, CA), April 16, 1885.

11 San Francisco Evening Bulletin, editorial, April 14, 1885.