Module 2: “In-Between” People

Can one family’s assertion of their civil rights become a “victory” for an entire community?

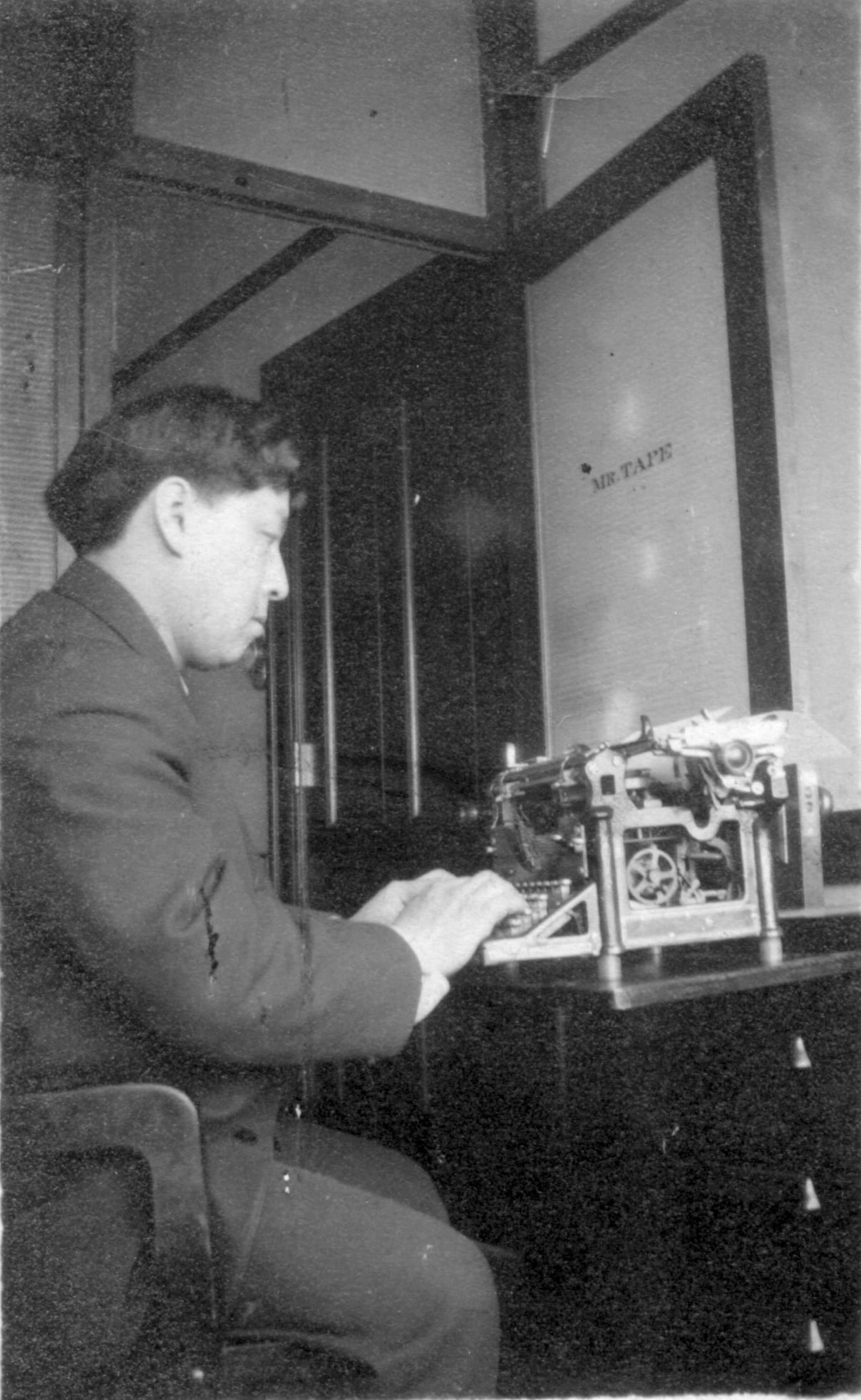

The Tape v. Hurley case introduced Joseph Tape and his family as Americanized Chinese who—unlike most Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth century—spoke English, became Christians, and adopted Western-style clothing and other American customs. Joseph, who started a business hauling goods for Chinese merchants from the docks to Chinatown, later became the official transportation agent for the Pacific Mail Steamship Company and the Southern Pacific Railroad. His son and sons-in-law also worked for the same steamship company, or as interpreters for the United States Immigration Bureau or the police courts.

The Tapes were immigrant brokers—middlemen who coordinated between government agencies or companies (e.g., steamships, railroads, and banks) and the Chinese people they worked with. Because brokers facilitated communication between two parties who otherwise cannot communicate with each other, both sides depended on them and the brokers possessed a lot of power. At the same time, it was common that neither side entirely trusted a broker. Some brokers helped immigrants gain citizenship, while others extorted immigrants and threatened to ruin their cases if they were not paid off. We will learn that the Tape family included both honest and corrupt brokers.

This module is about two generations of the Tape family who made their living as brokers. While their occupation gave them access to privileges of the white American middle class, that access was always limited. They would always be considered “in between” Chinese and white American society.

What was the Tape family’s background?

How did the Tape family build profitable connections not only with the Chinese immigrant community, but also with the White community?

Despite their position as “brokers,” what barriers did the Tape family still face due to their racial identity?

Chinese American: A New Identity

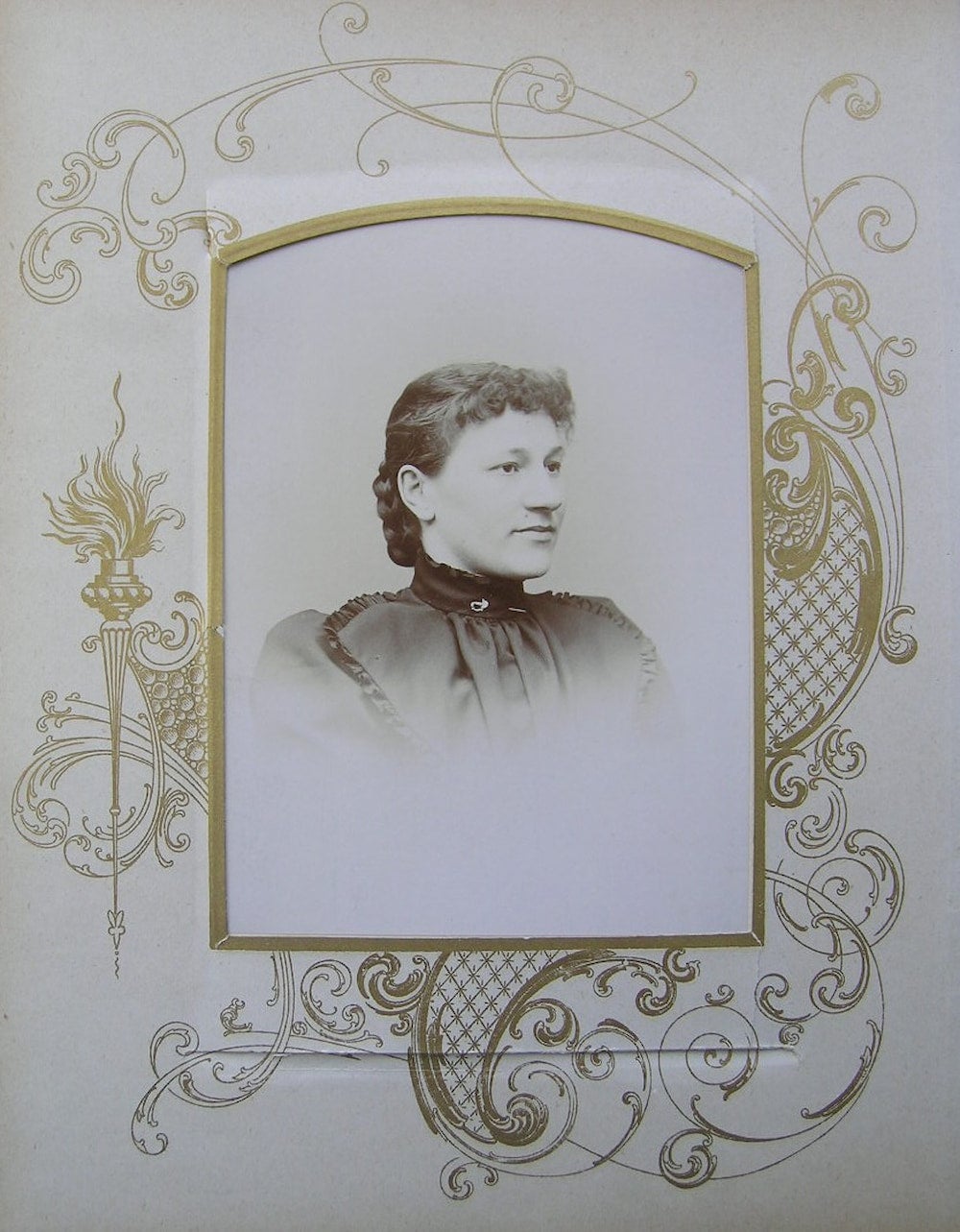

Mary was eighteen years old and Jeu Dip was twenty-three when they met in the spring of 1875. Because the Chinese Mary spoke was not a Cantonese dialect prevalent among the other immigrants in San Francisco, Jeu Dip courted her in English. They both spoke English well, having learned it at a young age and through virtual immersion. They were fast becoming “Chinese Americans.”

This new kind of identity did not really have a name at the time. No one used the term “Chinese Americans” to suggest assimilation or acculturation the way we understand Chinese American identity today. But unlike the vast majority of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco, Jeu Dip and Mary McGladery had come to the US without Chinese parents and lived among white communities. At the same time, they were the only Chinese in their worlds, thus marked by a double difference—different from the white people around them and different from other Chinese immigrants.

Six months after they met, on November 16, 1875, Jeu Dip and Mary were married at the Presbyterian church, although neither had been baptized. Jeu Dip took the name “Joseph Tape”—a Joseph to accompany his bride’s Christian given name, Mary. Tape was a German surname, perhaps chosen because “Joe Tape” sounded similar to Jeu Dip.

More to explore

Image

Reverend Augustus Loomis

Reverend Augustus W. Loomis was a Presbyterian missionary who sought to convert Chinese migrants in San Francisco to Christianity throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Prior to his work in California, Loomis worked at an Indian boarding school for Creek children. Indian boarding schools were abusive institutions that abducted Indigenous children from their homes and imprisoned them in residential complexes where students were forcibly “civilized” into white Christianity. Hundreds of Native children died in boarding schools, where they were subjected to attempted cultural genocide, unliveable conditions, and immense violence at the hands of their “caretakers.”

Image 37.02.04 — Photo of the Dupont and Sacramento streets (heart of the Chinese quarter) in San Francisco, circa 1895. Joseph Tape’s express office is in the second building on the left, with the horse and wagon in front.

Princeton University Press, 2010. Metadata ↗

Glossary terms in this module

Americanized Where it’s used

The process of assimilating to American culture, often experienced by immigrants as they are pressured to give up their heritage and cultural practices in favor of practicing American values and customs.

immigrant broker Where it’s used

A person who coordinates between government agencies or companies and the immigrant community they work with. Immigrant brokers often hold significant power because they possess the language and connections to communicate between the two parties.

assimilation Where it’s used

The process in which a group of people adapts to a dominant culture’s norms, language, values, and behaviors, either by choice or by force, in order to gain social acceptance and access to privileges.

acculturation Where it’s used

When individuals that are placed into a different culture adopt aspects of the prevalent culture while still holding onto their original values and traditions.

Endnotes

1 “Chinese Slave Girl Plot Foiled,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), November 27, 1912.