Module 3: The World’s Fair

Can one family’s assertion of their civil rights become a “victory” for an entire community?

In 1904, Joseph Tape devised a plan for his eldest children, Mamie and Frank, to attend the St. Louis World’s Fair (officially called the Louisiana Purchase Exposition). It was the United States’ fifth and largest world’s fair, running from April to December 1904. The fair was part of a tradition since the late eighteenth century, with countries hosting grand, months-long expositions that promoted international cultures and trade. The world’s fairs introduced the public to the peoples, histories, and industries of different countries. Western powers like the United States used the expositions to promote values of progress, expansion, and imperialism. They were also fun occasions, with games, rides, performances, and new innovations like the Ferris wheel and the ice cream cone.

Seeing an economic opportunity for his family at the St. Louis World’s Fair, Joseph arranged for Frank, Mamie, and her family, to work at one of the fair’s concessions: the Chinese Village. Frank and Joseph’s son-in-law, Herman Lowe, also started careers as immigration interpreters through the fair. This set them on the path that Joseph had pioneered as a broker in the immigration trade—arguably the best financial success path for their generation.

This module is about the Tape family’s experience at the World’s Fair of 1904, and how China and Chinese immigrants were represented on an international stage. The Tapes became culture brokers at a large-scale cultural extravaganza, in which China’s position in the world was recognized for the first time, but as a minor player; and where anti-Chinese immigration politics played out in dramatic ways.

What opportunities did the World’s Fair of 1904 provide for the Tape family to forge a new identity as Chinese American brokers in the interpreter class?

How did the Chinese Village reflect Western perceptions of China and Chinese exclusion laws?

How did gender of Chinese immigrants and workers affect how they were perceived in trafficking and smuggling schemes?

China at the World’s Fair

Although Chinese representatives participated in previous world’s fairs, China did not have an official pavilion at any international expo until the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. The Qing dynasty, which governed China at the time, built a miniature replica of the Dowager Empress’s Summer Palace and sent Prince Pu Lun, a nephew of the emperor, as its representative at this “Chinese Pavilion.”

The main Chinese attraction, however, was an exhibition of twenty thousand tons of goods sent by the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service, run by British and Americans. These goods were displayed at the Palace of Liberal Arts, a museum-like setting that featured civilizational achievements. But the exhibit was frankly commercial, aimed at developing trade relationships between the US and China. It included a few cultural and artisan exhibits like cloisonné and silk cloth manufacturing, which had commercial value. No Chinese art—such as China’s ancient bronzes, jade carvings, fine porcelains, paintings, or calligraphy pieces—had been represented in the Palace of Fine Arts, a separate exhibit that displayed art from various countries.

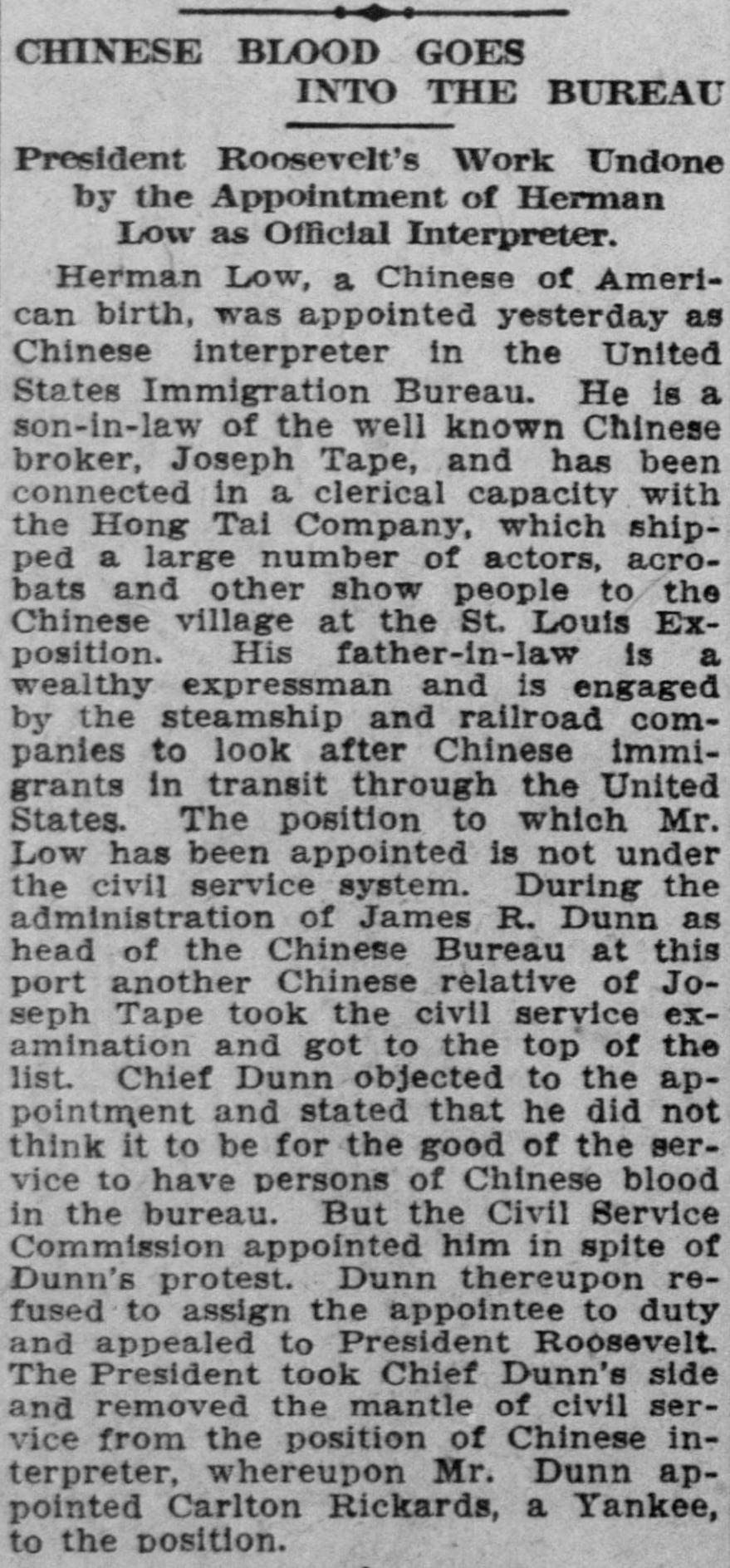

Image 37.03.01 — The Chinese Village on the midway at the St. Louis World’s Fair (1904). This exhibit promised visitors the chance to experience a romanticized version of the “Far East,” catering to white fantasies of China as an exotic kingdom lost in time. The Chinese Village employed Frank Tape and Mamie Tape’s husband, Herman Lowe.

Princeton University Press, 2010. Metadata ↗

The Chinese Village

The Tapes had no association with the official Chinese Pavilion. Instead, they worked for the “Chinese Village” on the fair’s midway, which was a separate section that featured novel and exciting commercial entertainment, including what Westerners considered exotic displays and stereotypical performances (belly dancing, snake charming, spear throwing) of “primitive” peoples. These were meant not only for entertainment but also to provide a contrast to the perception of Western nations as models for civilization. The general lesson was that European and American colonization was uplifting and progressive.

The Chinese Village had a good location on the midway near other pavilions, between the Siberian Railroad and Constantinople, and across from Cairo. It boasted a large structure with pagoda-inspired eaves and was ostentatiously painted in red and gold. There was a museum (“All the Odd Things of a Nation 4,000 Years Old”); a theater with jugglers, magicians, and acrobats; a restaurant and tea garden (“served by 50 Beautiful Chinese Girls”) 1; a joss house, or Chinese temple; a performance of a Chinese wedding; and a gift shop. As was the case of Chinese Villages at prior world’s fairs, it was sponsored by Chinese American entrepreneurs.

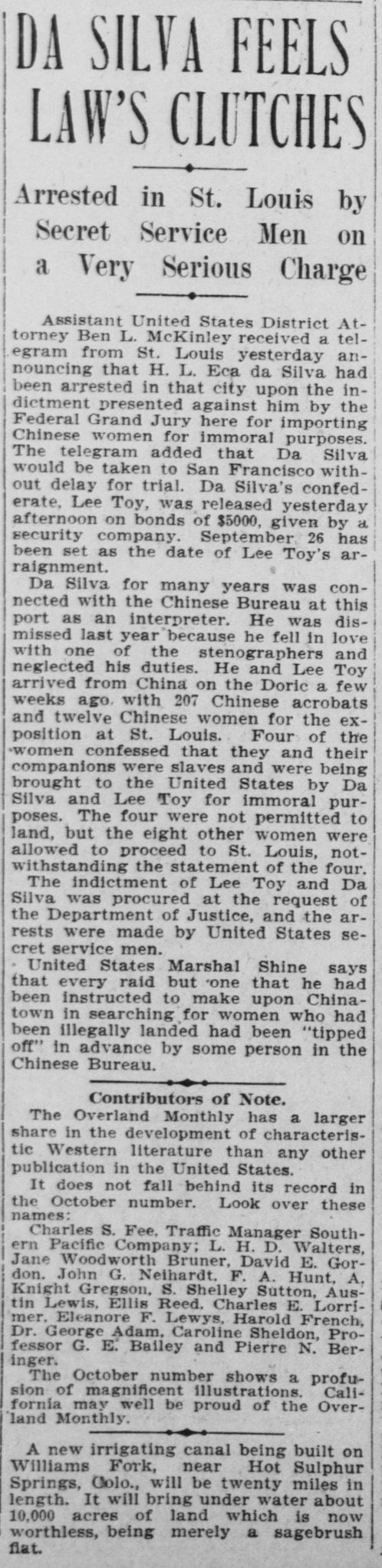

The Tape family worked in various roles at the Chinese Village. Frank and Herman were employees of the Hong Tai Company of San Francisco, which ran the concessions at the Village and hired 125 Chinese acrobats and other performers for the theater. The trip was a kind of junket, with all expenses paid. Frank managed the restaurant and Herman oversaw the concessions. Mamie watched her two young children, Harold and Emily, who also participated as fair entertainers. They were part of a group of about ten children—all with parents working for the Hong Tai Company—who wore Chinese costumes and ran around the midway with flyers promoting the Chinese Village. Fairgoers assumed they were from China, but in fact they were American-born US citizens. Emily, the youngest child in the group, was featured in fair guidebooks as a kind of scientific specimen: “Emily Lo, one of the many bright children in the ‘Chinese Village.’ This little girl is a full-blooded Mongolian 3 years old and measures only 2 ½ feet in height. The pride of the ‘Chinese Village’.” 2

Image 37.03.02 — Children of Chinese American merchants were employed in the Chinese Village and costumed to appear as though they were from China. Mamie’s children, Harold (front row, right) and Emily (front row, third from right), were part of this group.

Princeton University Press, 2010. Metadata ↗

Glossary terms in this module

deportation Where it’s used

The violent and forced removal of a person or group of people from a country.