Module 4: The Strange Career of a Chinese Interpreter

Can one family’s assertion of their civil rights become a “victory” for an entire community?

Frank Tape’s career as an immigration interpreter was unusual from the start. He had won the approval of Inspector James Dunn at the World’s Fair of 1904, not because he excelled at interpreting, but because of his work as an undercover informant. In 1908, the Washington, DC, headquarters of the US Immigration Bureau assigned Tape to be the interpreter for Richard Taylor, a special agent investigating the smuggling of Chinese migrants across the Mexican border. At his next assignment in Seattle, Washington, Frank Tape used his stint on the border to promote his reputation. But Tape also sought status and personal wealth through corrupt practices, ultimately leading to criminal charges and his dismissal from the bureau.

This module uses Frank Tape’s background as an immigration interpreter to explore the darker side of the immigrant broker’s experience, including how brokers gained social and financial success at the expense of oppressing and extorting others. It also shows how immigrants themselves often sought the help of Chinese immigration interpreters, sometimes naively, and sometimes through bribery.

How did Frank Tape further his parents’ goal of aspiring toward inclusion in white society?

How did Frank Tape’s attempts to fully assimilate lead both to his ascension as well as his downfall?

How did Chinese people respond to unjust exclusion laws?

Seattle Investigator

In September 1908, Frank Tape reported to the Seattle District Office, his next assignment with the Immigration Bureau. The city was a major port in transpacific migration. Thousands of people from China, Japan, and India arrived there every year. The Seattle district also processed documents for immigrants arriving by land and monitored the US-Canada border for Chinese smuggling.

Frank Tape arrived in Seattle boasting that he had just come from a special undercover assignment on the Mexican border and that he had direct ties to Washington, DC. Although his job as a Chinese interpreter was a conventional one, he maneuvered himself into the role of investigator by offering to take on Chinese smuggling cases that the inspectors could not solve. In one case, he uncovered an operation run by one of Seattle’s wealthiest Chinese residents, Ah King, who used his merchant business as a front for forty-four “partners” who took turns bringing in their “sons.” Ah King also reportedly opened the Chinese Village attraction at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle to bring in unauthorized immigrants, similar to the scheme at the World’s Fair of 1904 in St. Louis.

Frank Tape established himself in Seattle’s Chinatown as a government man, a position of social importance in the community. People knew him as a successful interpreter and did not know that he worked undercover; that would have destroyed his reputation. Tape also used his status and connections to invest in contracting Chinese workers for seasonal work in the Alaskan fish canneries, another type of brokering.

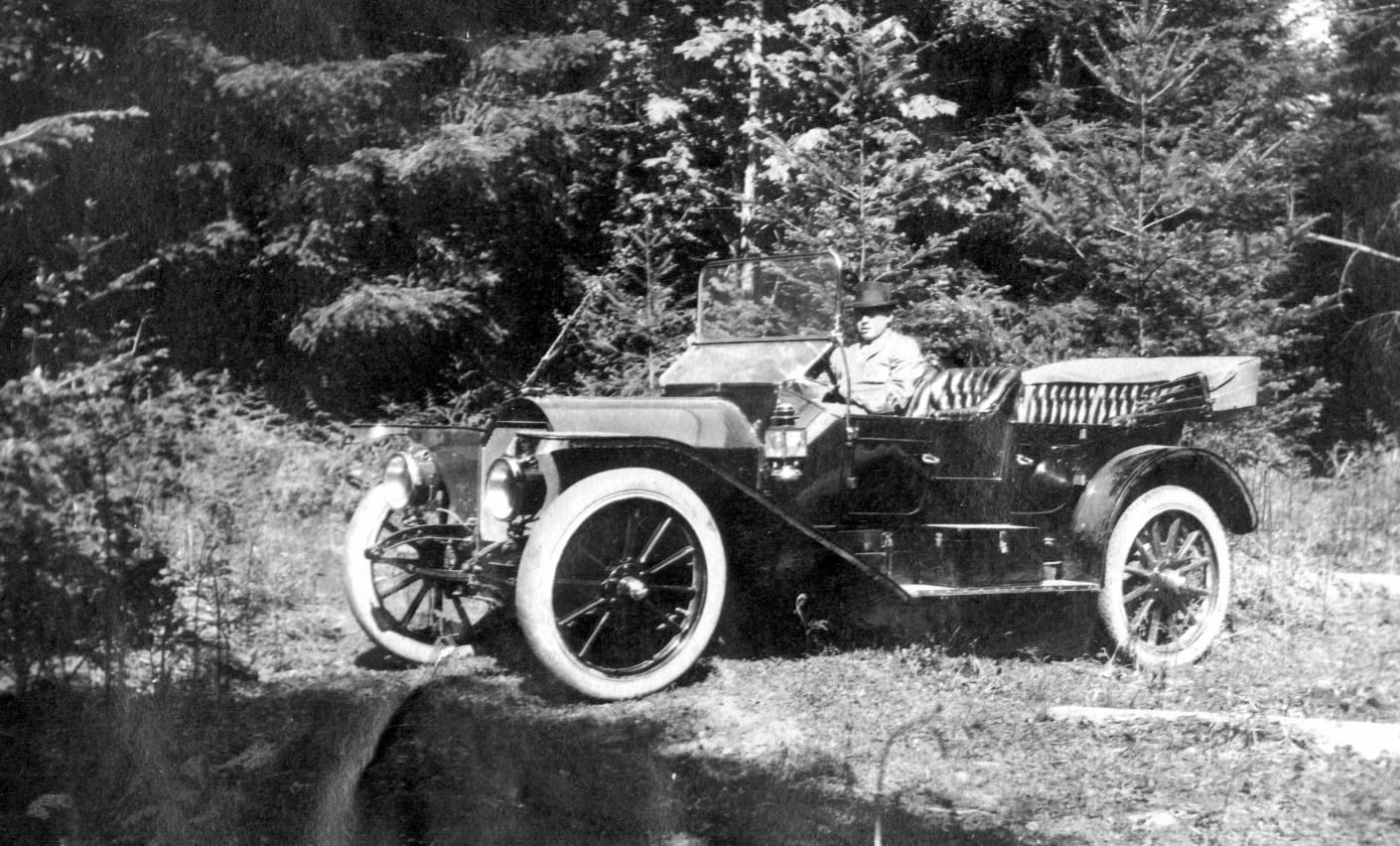

Among white people, Tape presented himself as white. He lived in a white section of town, drove a fancy car, and wore expensive suits. In the 1910 Census, he even reported his race as white. In 1911, he began living with a white woman, Lena Sutherland, a divorcée originally from Pennsylvania. In Seattle’s polite society, some people disapproved of interracial relationships; but others conceded that he had come closer than any Chinese in achieving acceptance by white society.

Frank Tape’s unusual lifestyle prompted both resentment and suspicion among his colleagues. Within a year of his arrival in Seattle, Tape’s coworkers began to raise questions about him especially after he took up residence with Lena Sutherland. Tape’s lifestyle became even more extravagant, from employing a chauffeur and maid to going on hunting and fishing trips. Sutherland spent heavily on clothes and jewelry. And so many wondered, how did a government salary support such expensive habits?

When Henry White took office as Seattle’s new commissioner of immigration in 1913, he launched a secret investigation into Frank Tape’s finances. Bank statements revealed that the couple, who married in 1912, was spending upwards of $8,000 a year (worth $200,000 today).

Tape was also questioned by the Walsh Commission, a federal body appointed by Congress to investigate labor conditions and what they called “Asiatic smuggling”—under the presumption that Chinese labor in the US undermined white labor. The commission was particularly interested in Frank Tape’s racial identity. According to official records, the commission asked, “What is Tape’s race?” and “Full, half, or quarter?” 1, reflecting the stereotypes held by many whites that a person who is Chinese could not possibly be “American.” They also questioned the financial and moral standing of his white wife. Richard Taylor, his former colleague at the Secret Service, defended Tape as a friend and a trustworthy investigator. But this was not enough to deter the case that was building against Tape.

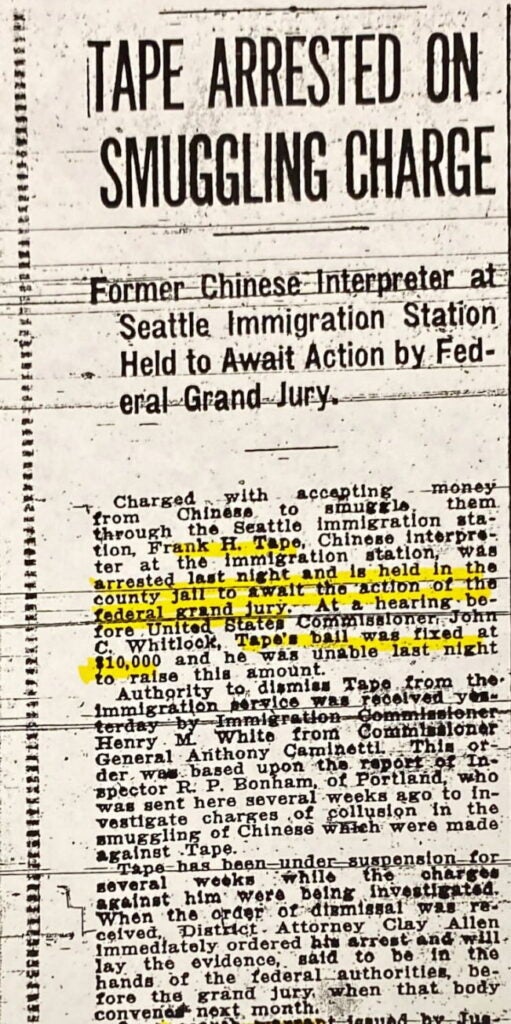

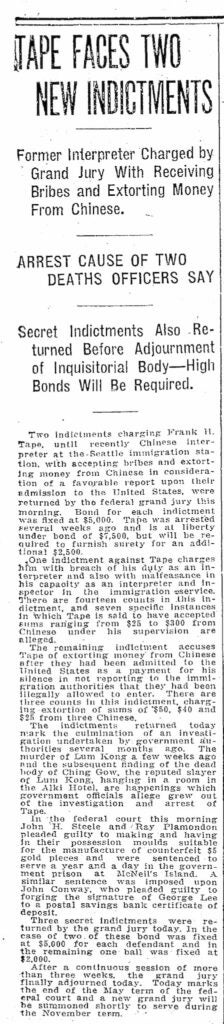

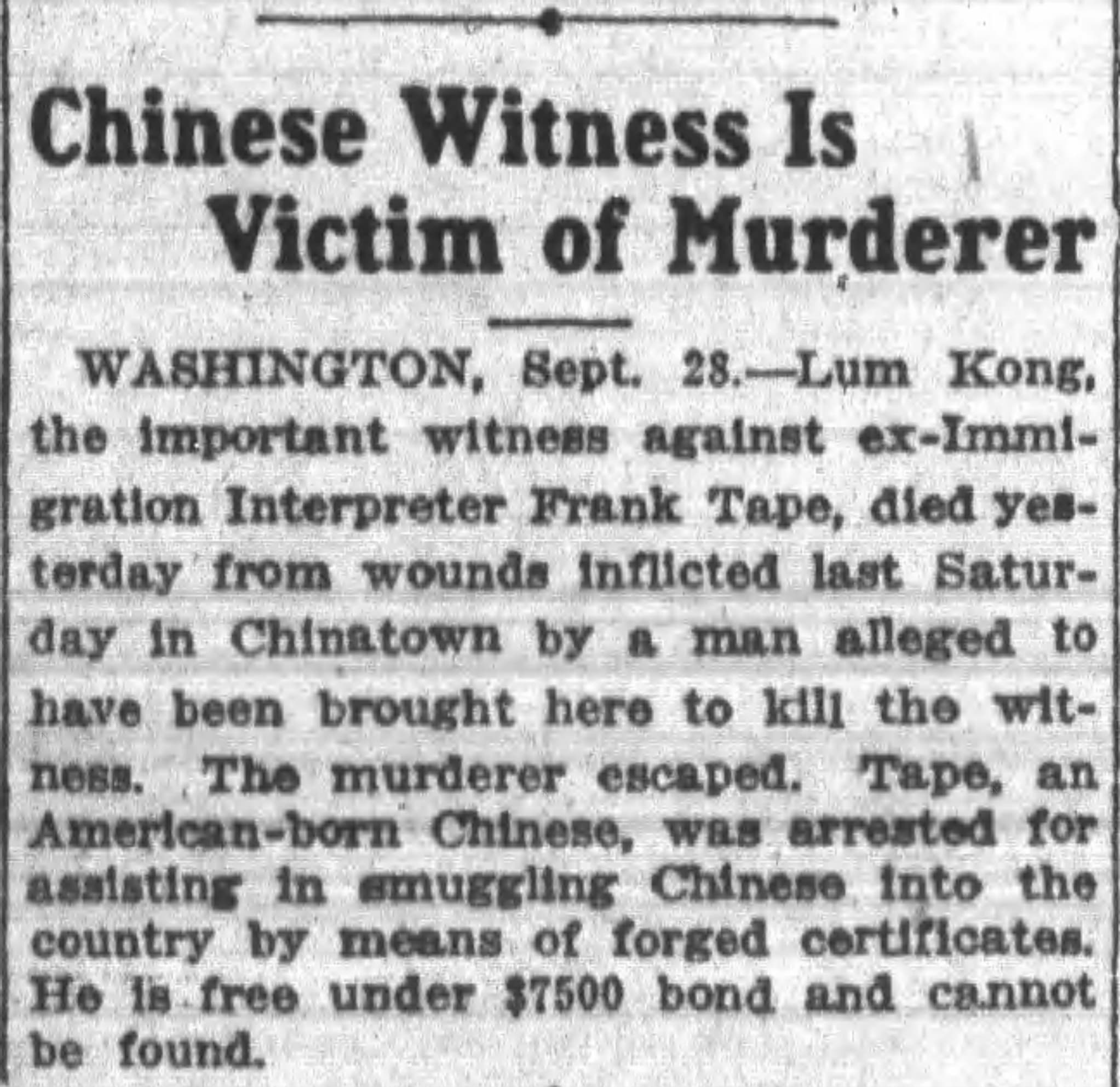

Immigration Commissioner White’s inquiry concluded with an eighty-one page report that included Tape’s bank statements and testimonies from several dozen witnesses, Chinese and white. It concluded that Frank Tape operated an extensive extortion racket and was possibly expanding his network to Mexico. He was dismissed from his position with the bureau and then arrested by the US attorney on criminal charges related to extortion in Chinese immigration cases.

Corruption at Angel Island

It is important to remember that the systems of processing Chinese immigration cases, both legally and through covert means, extended beyond the work of interpreters. A few years after Frank Tape’s trial, a major scandal took place at Angel Island, located in California’s San Francisco Bay, the largest port of entry for Chinese immigrants.

The Angel Island Immigration Station had been built in 1910 in an effort to isolate arriving Chinese migrants from their relatives or their representatives from family associations, who would usually provide the new immigrants with information to help pass the interview process. But Angel Island could not be completely contained—the station’s staff, officers, and food supplies had to be ferried to the island every day.

Image 37.04.04 — Immigration station on Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay, circa 1915.

Courtesy of Library of Congress. Metadata ↗

In 1917, a major investigation of Angel Island Immigration Station found an extensive system of manipulation and theft of documents, extortion of money from immigrants, and fraud in applicants’ examinations. This underground system was estimated to bring in $100,000 per year (worth $1.6 million today), and involved the station’s clerks, stenographers, typists, watchmen, inspectors, and interpreters—as well as outside law firms, brokers, photographers, and counterfeiters—and only a few were Chinese. As an immigrant broker in San Francisco, Joseph Tape was not suspected of any wrongdoing. But Edward Park, the brother-in-law of Joseph’s daughter Emily, who worked as an interpreter, was among those fired. Fifteen people were indicted on charges of conspiring to mutilate government records to land immigrants illegally.

People in San Francisco’s Chinatown were overjoyed to learn of the dismissals and indictments. As one person wrote to the bureau, “You have done a great justice to our Chinese peoples. That is, you have made a clean sweep oust all the crooks, and grafters, which is in Angel Island.” 2 For the immigrants arriving, the oppression of the exclusion laws was compounded by the burden of having to pay bribes to get through the system—even if they were legally eligible for admission.

Many in the Chinese community believed that the exclusion laws themselves were unjust and immoral—how does this impact our understanding of what was “honest” or “corrupt” at the time? Most Chinese did not consider it morally wrong to enter the country, even if they knew it was against the law. Immigrants often expected the Chinese interpreters to help them, either because they believed their families in the US had paid them off or because they simply assumed they could trust another Chinese person. As seen in these corruption cases, however, immigrants could make no assumptions about a Chinese interpreter’s loyalties.

The scandals at Angel Island reveal a dense web of practices and transactions that complicated the administration of the Chinese exclusion laws. Contrary to the heightened, racialized publicity surrounding Chinese immigration cases in news media, corrupt business practices were not a problem solely among Chinese workers. In the Angel Island case, white brokers and lawyers made the most money, while Chinese brokers were the small fry, earning a modest cut lower down the chain. Still, these bribes and extorted funds gave Chinese brokers access to a more comfortable life that remained out of reach for the vast majority of Chinese Americans in the twentieth century. In this way, the murky moral world created by the Chinese exclusion laws led to the experiences of brokers like Frank Tape as “in-between” figures of class and racial identity.

Glossary terms in this module

Angel Island Where it’s used

Located in the San Francisco Bay, this island served as the primary immigration port for the West Coast of the United States from 1910 to 1940.

extort/extortion Where it’s used

A criminal offense; when someone uses violence, threats, intimidation, or pressure to force another person to give them money or benefits.

immigrant broker Where it’s used

A person who coordinates between government agencies or companies and the immigrant community they work with. Immigrant brokers often hold significant power because they possess the language and connections to communicate between the two parties.