Module 1: Overview & Introduction

How can an entire racial group be unjustly incarcerated in a democracy?

Between 1942 and 1946, the US government imprisoned 125,000 Japanese Americans in camps throughout the United States. None of them had committed any crime. About two-thirds were American citizens. The government justified this unprecedented denial of constitutional rights on “military necessity” because the United States was at war with Japan. But in the 1980s, researchers found evidence that during World War II, government officials forced Japanese Americans to leave the West Coast because of racist ideas about them, not military need.

For decades prior to World War II, Japanese immigrants (known as Issei) and their American-born children (known as Nisei) were the targets of intense discrimination. That history set the stage for the government to incarcerate Japanese Americans after Japan attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaiʻi.

Why and how did the United States government decide to mass incarcerate Japanese Americans during World War II?

How did the movement for Japanese American reparations develop and why was it successful?

What did Japanese Americans experience when they were removed from their homes and imprisoned?

Immigrants from Japan and Their Reception in the United States

Many Japanese immigrants arrived in the United States after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was fueled by anti-Chinese racism, particularly in California, and legally barred most immigrants from China. Agricultural, mining, and lumber business owners in the western United States recruited Japanese men to fill the labor vacuum that Chinese immigrants previously occupied. But Japanese immigrants were soon unwelcome.

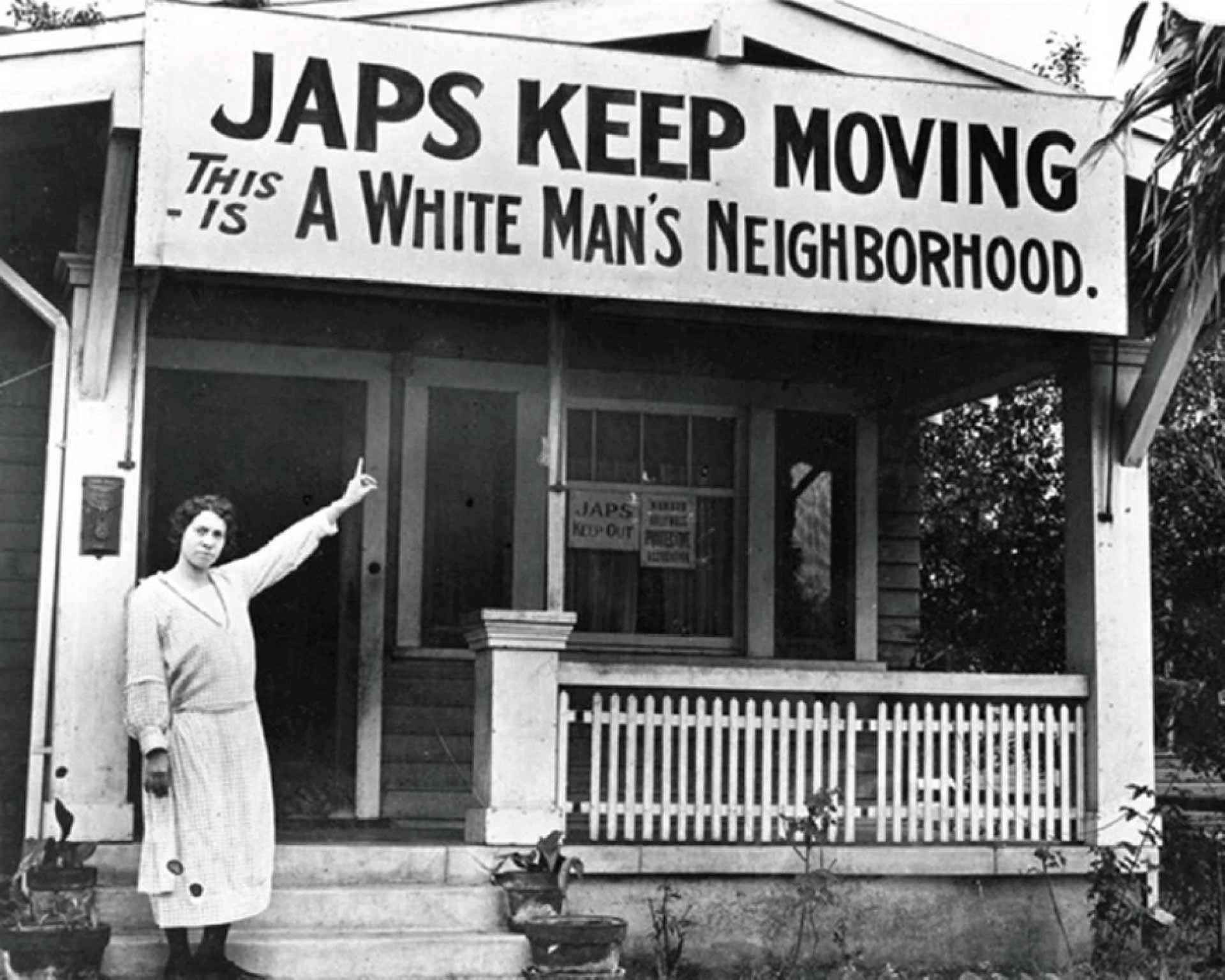

Racism sparked fears that Japanese would settle in the United States. Starting in 1913, Oregon, California, Washington, and twelve other states passed “Alien Land Laws” denying Japanese immigrants the right to own or lease land. A 1922 United States Supreme Court ruling, Ozawa v. United States, upheld a law barring Japanese and other Asians from becoming naturalized citizens.

A growing movement of anti-Japanese exclusionists persuaded Congress to pass the Immigration Act of 1924, which barred all Japanese immigrants and legally ended immigration from Asian countries. The Philippines, which was then a US colony, was an exception.

Communities Thrive Despite Discrimination

Despite rampant anti-Japanese sentiments, vibrant Japanese American communities thrived along the West Coast. During the 1920s and 1930s, Japanese American-owned businesses clustered in “Japantowns” in Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, Sacramento, Seattle, and elsewhere. Issei were successful farmers, flower growers, and fishermen. Issei and Nisei formed cultural, social, professional, and political organizations. Pre-World War II Japanese American communities flourished as they established organizations, classes for youth, festivals, and celebrations.

New generations of Japanese Americans grew. American-born children were citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment, which gave citizenship to those born in the United States. They had the right to life, liberty, and property with equal protection of the laws. This amendment is especially significant in showing how Japanese Americans’ constitutional rights were violated.

Image 45.01.02 — Masuo Yasui led a successful effort to create a Japanese Community Hall in Hood River, Oregon, where local Issei held cultural events, holiday gatherings, and Japanese language classes for children.

Courtesy of Densho, Yasui Family Collection. Metadata ↗

The Road to Mass Incarceration

Long before the Japanese military attacked the US base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, unsubstantiated rumors circulated about Japanese Americans engaging in sabotage. US officials compiled lists of Issei they considered suspect because of their leadership in community and cultural organizations. Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin Roosevelt invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, authorizing FBI agents to arrest and imprison Issei leaders indefinitely without charges, and to freeze all Issei bank accounts. The government also instituted an 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew on German and Italian immigrants and all people of Japanese ancestry, even American citizens.

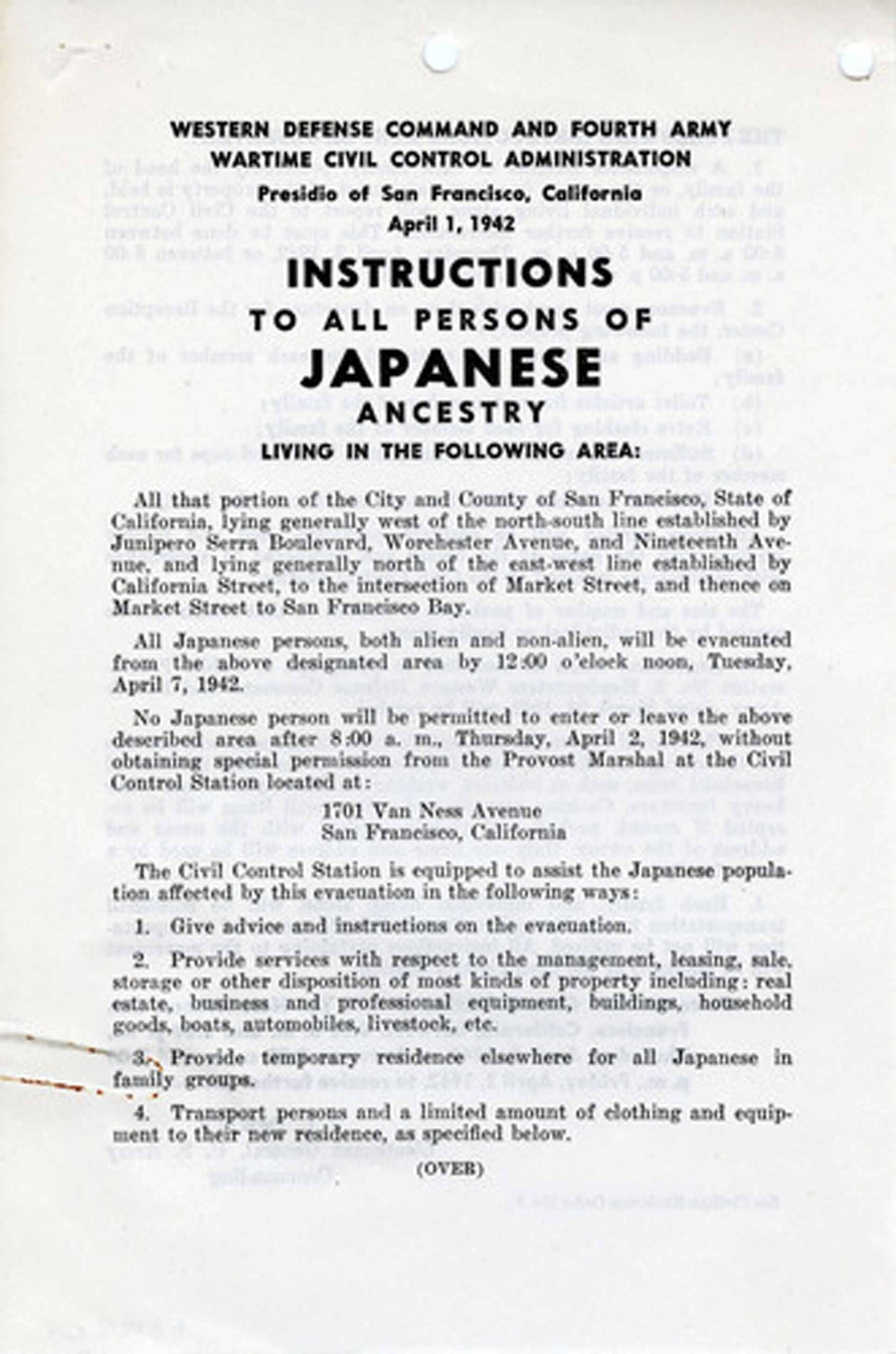

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which empowered the Secretary of War and designated Military Commanders to prevent anyone from entering or remaining in locations designated as “military areas.” Soon, the military commander of the West Coast ordered the western portions of Washington and Oregon, the southern part of Arizona, and all of California off-limits to Japanese Americans.

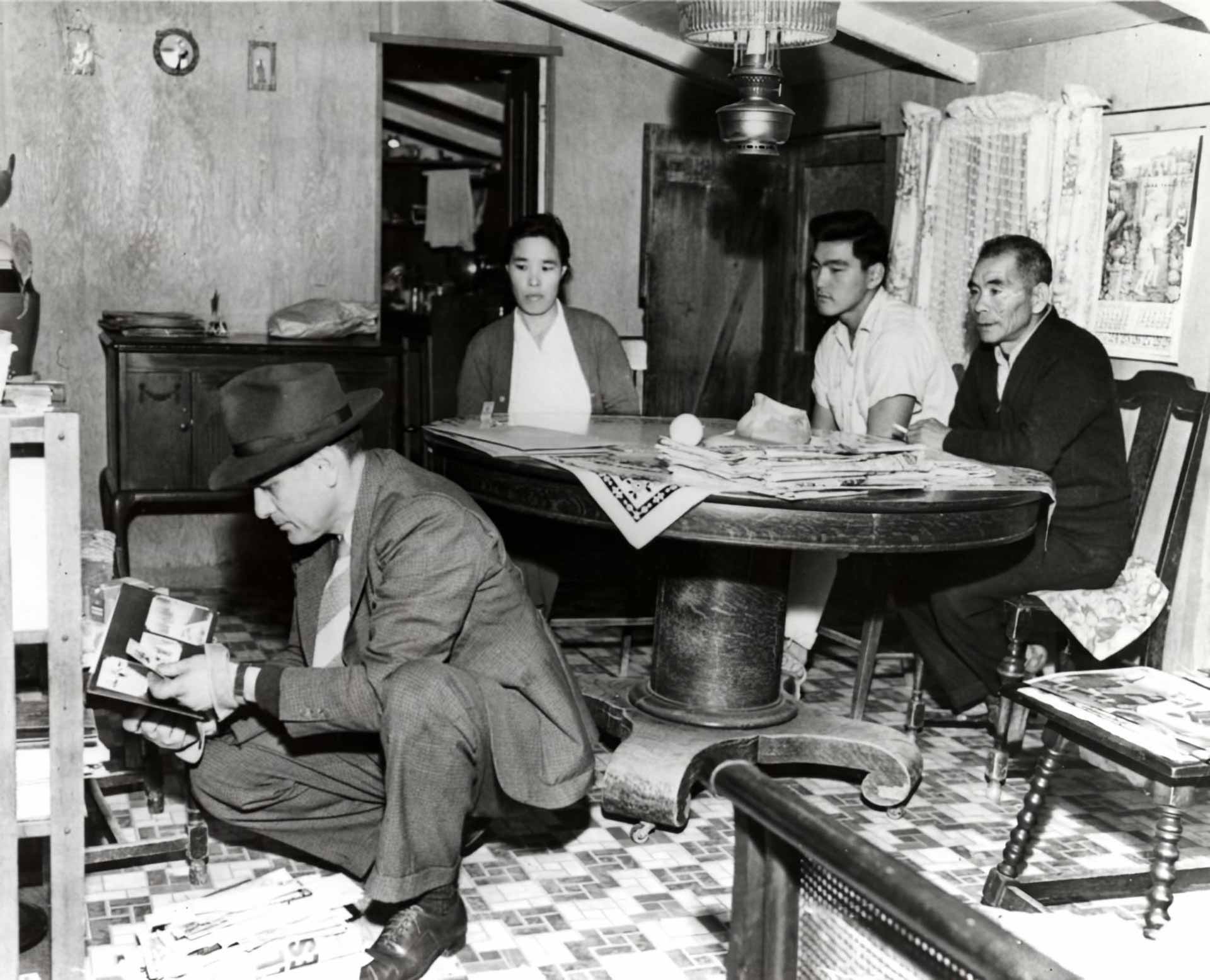

In the days after the bombing, government agents searched Japanese American homes for contraband. Agents took cameras, weapons, and any evidence of a connection with Japan. As news spread within Japanese American communities about these searches, many people destroyed books and letters written in Japanese, photos of relatives, and priceless art and artifacts from Japan.

FBI agents searched the Yasui family home and arrested Masuo Yasui days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. White farmers and businesspeople in Hood River speculated that government officials took him away because he was a spy. Japanese Americans feared the government would shoot or deport Issei leaders, like Yasui, who had been arrested yet had done nothing wrong.

Officials instituted these policies despite the findings of government-commissioned reports, which concluded that Japanese Americans were overwhelmingly loyal to the United States and that mass exclusion was unnecessary.

Image 45.01.03 — FBI agents searched the homes of many Japanese American families, like this one, and the Yasui family in Hood River, Oregon.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Metadata ↗

Forced to Leave Home

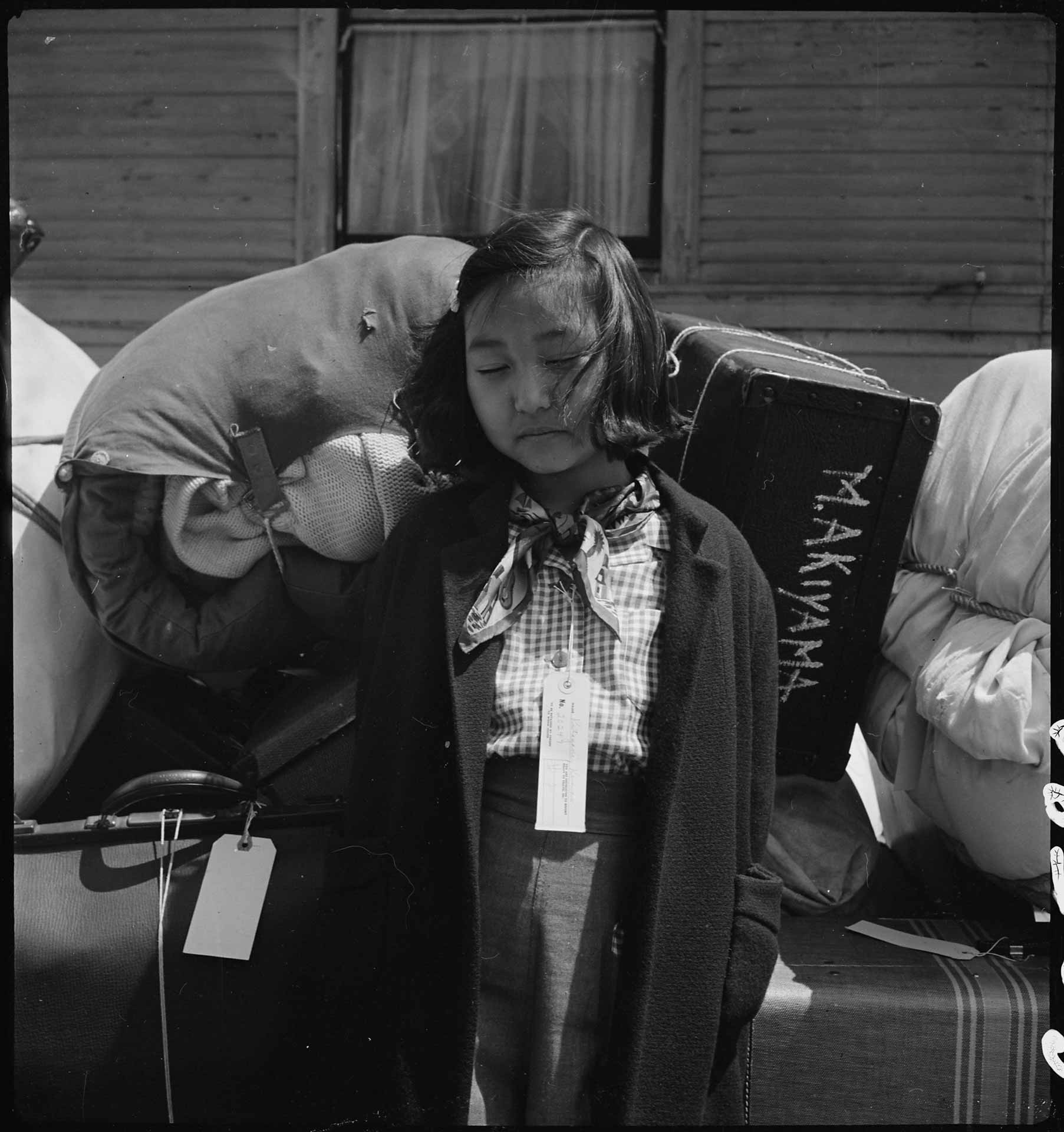

In the spring of 1942, the government forced all Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to leave their homes. Frantic families had weeks, sometimes only days, to decide how to close businesses and farms, what to sell, and what to take with them. They could only take what they could carry.

More to explore

Video

06:59

Leaving Home

Japanese Americans recount the fear prevalent after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and what it was like to be forced from their homes.

Temporary Homes

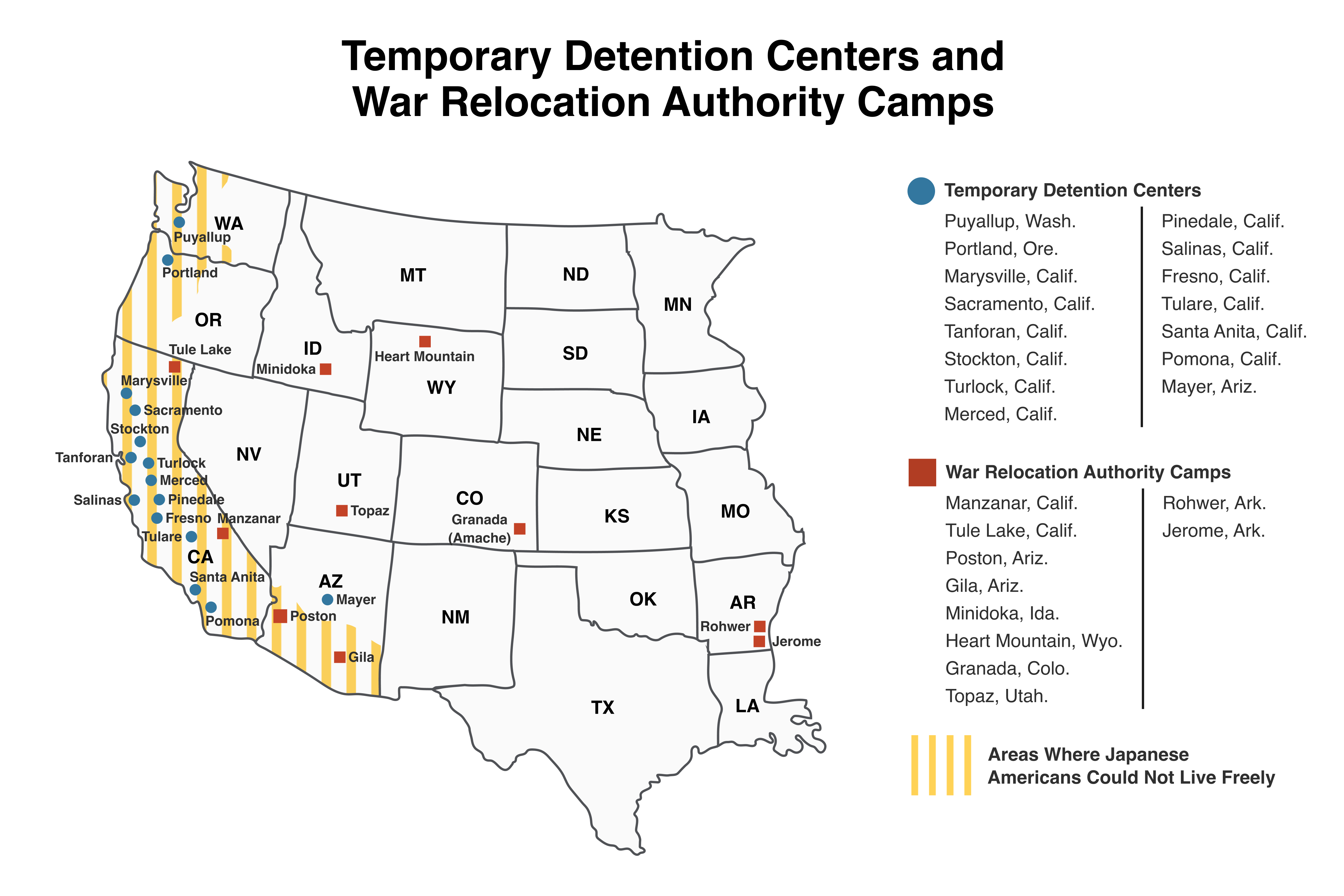

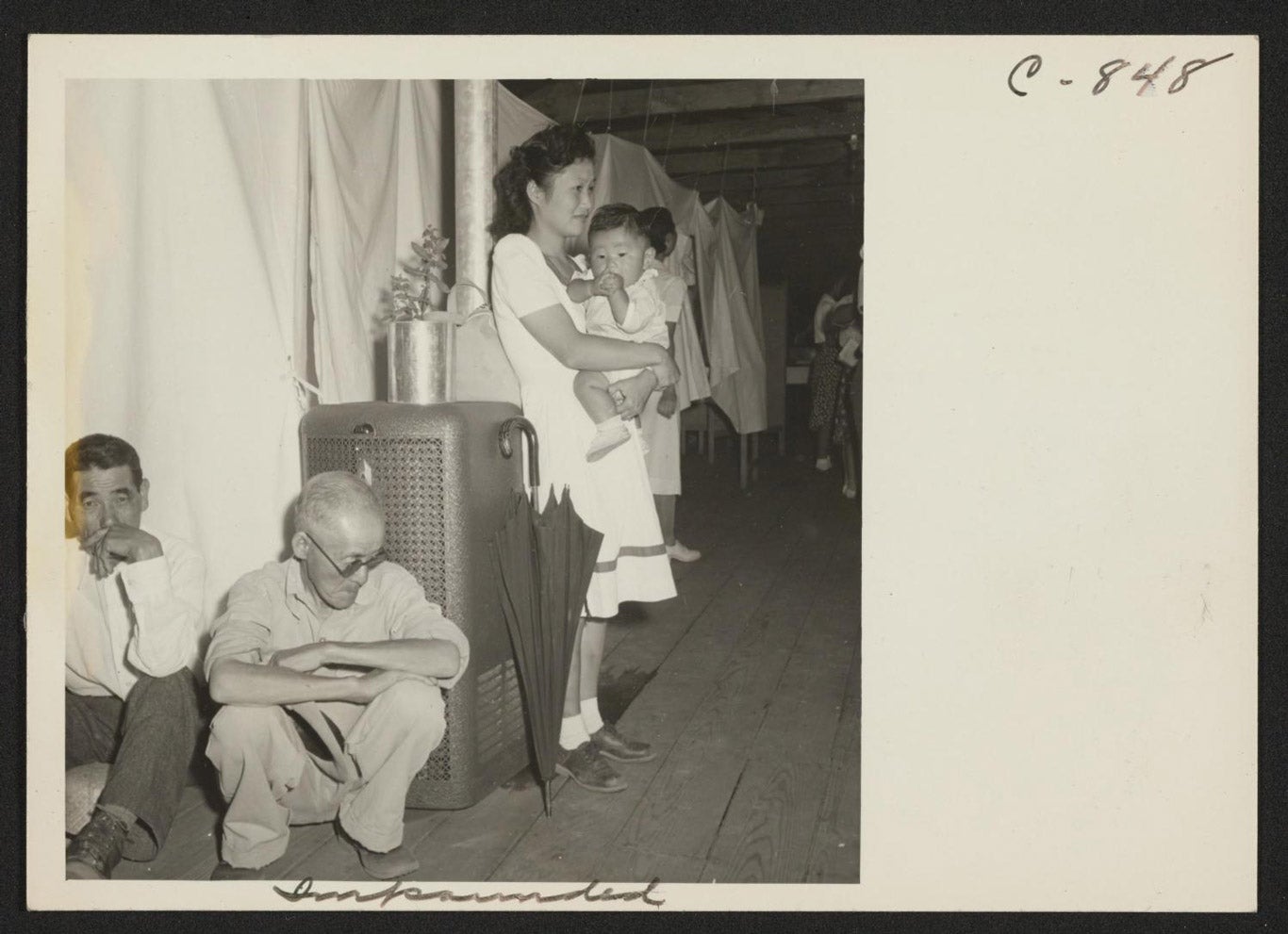

The government sent Japanese Americans to fifteen temporary camps, euphemistically called “assembly centers”, hurriedly built on fairgrounds, livestock pavilions, and horse racing tracks. Japanese Americans lived in horse stalls and barracks. The only furnishings were iron cots and a single light bulb. They ate in mess halls and used communal latrines.

Masuo Yasui’s family were one of thousands that the government forcibly removed. The military forced Shidzuyo Yasui and her teenage children from their home in Hood River, Oregon, and sent them to an “assembly center” called Pinedale in Fresno, California.

Moved Once Again

In the summer of 1942, the government transferred Japanese Americans from the assembly centers to ten more permanent camps, administered by a federal agency called the War Relocation Authority (WRA), and located mostly in deserts and swamps throughout the United States.

The WRA camps replicated the structure of the “assembly centers,” with barracks divided typically into four to six rooms. Barracks were grouped into “blocks,” each with a mess hall and communal latrine. Barbed wire fencing ringed the camps, punctuated by guard towers staffed by armed soldiers.

The government sent the Yasui family to a camp called Tule Lake in California. Yuka Yasui started attending the camp’s high school as soon as it opened in the fall of 1942. But there were no desks, chairs, books or supplies yet. Japanese American teachers and instructors from outside the camps taught at the schools.

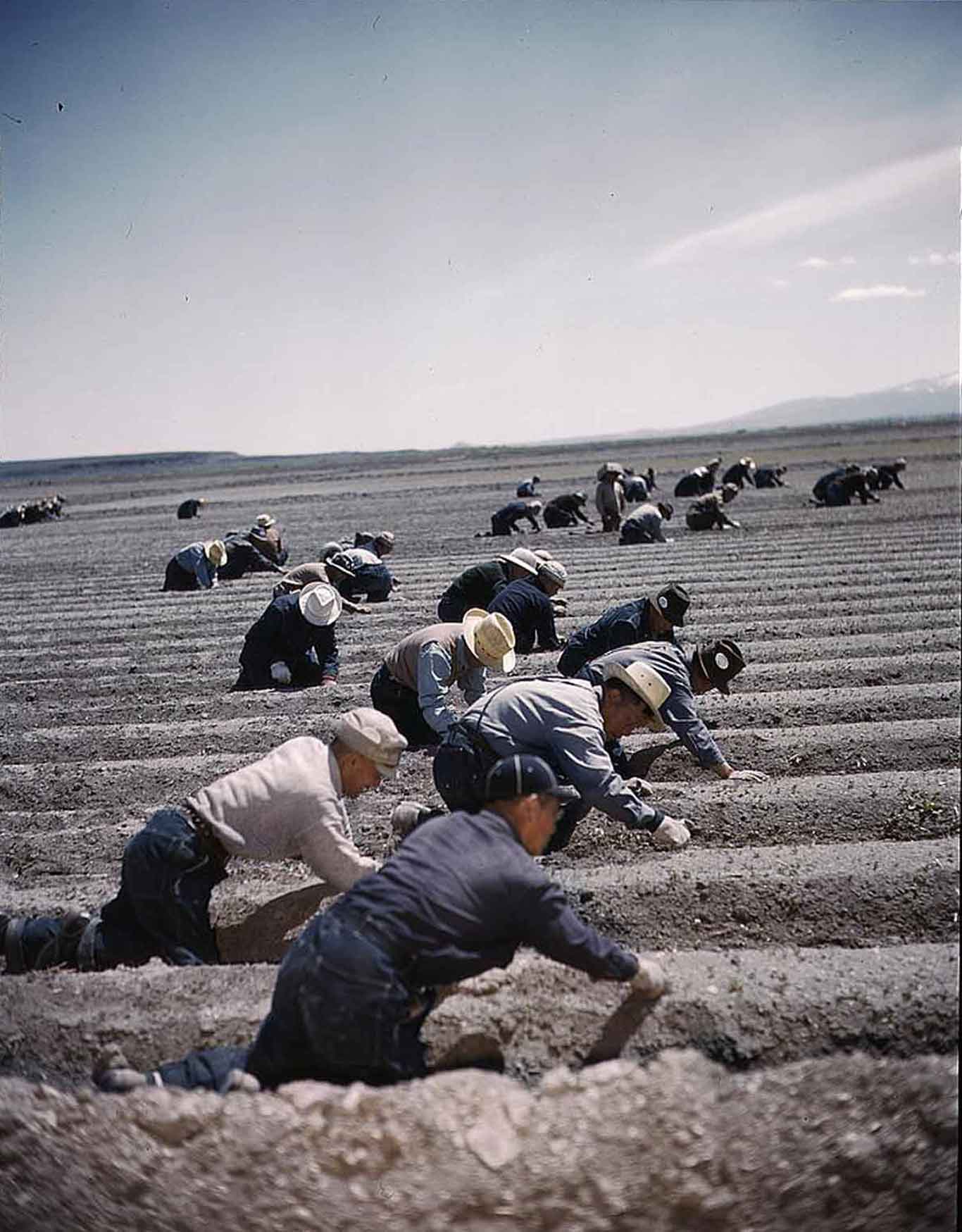

The WRA set up the camps to be as self-sufficient as possible. Inmates worked in mess halls, hospitals, schools, administrative offices, and other locales within the camps. Japanese American workers received twelve to nineteen dollars a month. White workers in the camps earned more than ten to twenty times as much. To cope with boredom, inmates organized arts and cultural clubs and athletic leagues.

More to explore

Video

05:05

Camp Life From Those Who Lived It

In this short video, Japanese Americans’ accounts of life in the camps contrast with the government’s depiction of them.

Who’s “Loyal”?

In early 1943, the US Department of War decided to form an all-Nisei combat team recruited from Hawaiʻi and the WRA camps. At the same time, the WRA wanted to disperse Japanese Americans in colleges and jobs throughout the country so that they would assimilate. The two government entities collaborated to create a questionnaire to determine the loyalty of potential soldiers and inmates who would be allowed to leave the camps.

WRA officials required all inmates older than seventeen to complete a questionnaire called an “Application for Leave Clearance.” Two questions generated confusion and resentment among many inmates: One asked about their willingness to serve in the armed forces. The second asked respondents to forswear allegiance to Japan and to swear unqualified allegiance to the United States. Many men were wary of answering “yes” to the first question, unsure whether a positive response would mean automatic induction into the US army. Answering “yes” to the second question could imply that people had previously been loyal to Japan. In addition, Issei, who were not allowed to become US citizens at the time, feared that answering “yes” might mean renouncing their Japanese citizenship, leaving them stateless.

Image 45.01.09 — In early 1943, military recruiters visited the ten WRA camps. About 1,500 Nisei men volunteered. They joined nearly ten thousand Japanese American volunteers from Hawaiʻi to form the 442nd Regimental Combat Team which fought in Europe. Many of its members served and died while their families were imprisoned in the US.

Courtesy of Densho, Seattle Nisei Veterans Committee Collection. Metadata ↗

The vast majority of inmates answered “yes” to both questions. Beginning in May 1942, the government granted seasonal leaves to Japanese Americans who answered the loyalty questions positively. Labor shortages compelled farmers to ask the government to give Japanese Americans temporary leaves for agricultural work in Utah, Montana, Idaho, and other states. Ray “Chop” Yasui, the eldest Nisei of the Yasui family, secured a year-long “seasonal pass” in the spring of 1943. The pass allowed him, his wife, and their child to leave Tule Lake for a farm near Great Falls, Montana.

Aided by the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, some Nisei left camps to attend colleges outside the exclusion zone. Homer Yasui was one of them. He left Tule Lake for the University of Denver. Later, his younger sister Yuka left Tule Lake bound for Denver to attend high school. By the end of the war, 4,300 Nisei had left the WRA camps for colleges.

A significant fraction of Japanese Americans answered “no” or refused to answer the loyalty questions. Some were frustrated that the government questioned their loyalty while imprisoned. Others answered negatively because they were disillusioned about losing their constitutional rights. Some wanted to explain that they would answer “yes” to both questions if freed. But the government only allowed “yes” or “no” responses, and considered all “no” answers as proof of disloyalty.

In June 1943, WRA officials designated the Tule Lake camp as a “segregation center” for inmates who had answered the problematic loyalty questions negatively.

Challenging Forced Removal and Incarceration

In 1942, four Japanese Americans (including Minoru “Min” Yasui, who was part of the Yasui family) filed lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of wartime policies targeting Japanese Americans. Their cases reached the US Supreme Court, which ruled that the curfew and forced removal orders for Japanese Americans were constitutional, but that indefinitely incarcerating loyal Japanese Americans was not.

More to explore

Video

06:18

Responses to Incarceration

Japanese American men recount their reactions to incarceration, the draft, and their experiences fighting in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Closing the Camps: Where’s Home Now?

On December 17, 1944, the US Department of War announced that Japanese Americans could return to the West Coast effective January 2, 1945. The WRA then announced that all the camps under its jurisdiction would close by the end of 1945, more than three years after the first Japanese Americans were imprisoned.

More than two-thirds of the eighty thousand Japanese Americans still living in the WRA camps returned to the West Coast. But most had no homes or jobs awaiting them.

Returning Japanese Americans, especially in rural areas, encountered vigilante violence and threats meant to terrorize them to leave. In Hood River, Oregon, where the Yasui family had previously lived, the local chapter of the American Legion organization removed the names of all Japanese American soldiers from the county’s war memorial. The action drew condemnation across the US. Even the national commander of the American Legion was critical. After several months, the American Legion chapter added back the Japanese Americans’ names.

Japanese Americans returning to urban areas faced housing challenges. Many of them initially lived in hostels, often set up in Japanese American Christian churches and Buddhist temples. Eventually, the federal government established emergency housing in army facilities and trailer parks.

Image 45.01.11 — This family returned to their home in Seattle, Washington, from a camp at Minidoka, Idaho, to find their garage vandalized.

Courtesy of Densho, Haruko Nagaishi Collection. Metadata ↗

Because of continued racial discrimination and anti-Japanese prejudice, returning Japanese Americans also had difficulty finding employment. Having lost their prewar businesses, and without capital to restart, many took low-wage jobs as janitors, domestic servants, and caretakers.

The Fight for Redress and Reparations

Decades later in 1970, Edison Uno, a Nisei activist with the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), advocated that Japanese Americans demand reparations from the US government for their unjust imprisonment. But most Issei and Nisei did not want to discuss the war years even within their families.

Nevertheless, support for redress grew steadily throughout the 1970s and 1980s from within the Japanese American community and from allies, including African American members of Congress. The movement for redress and reparations advanced when Congress authorized a commission to study the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans and to recommend remedies.

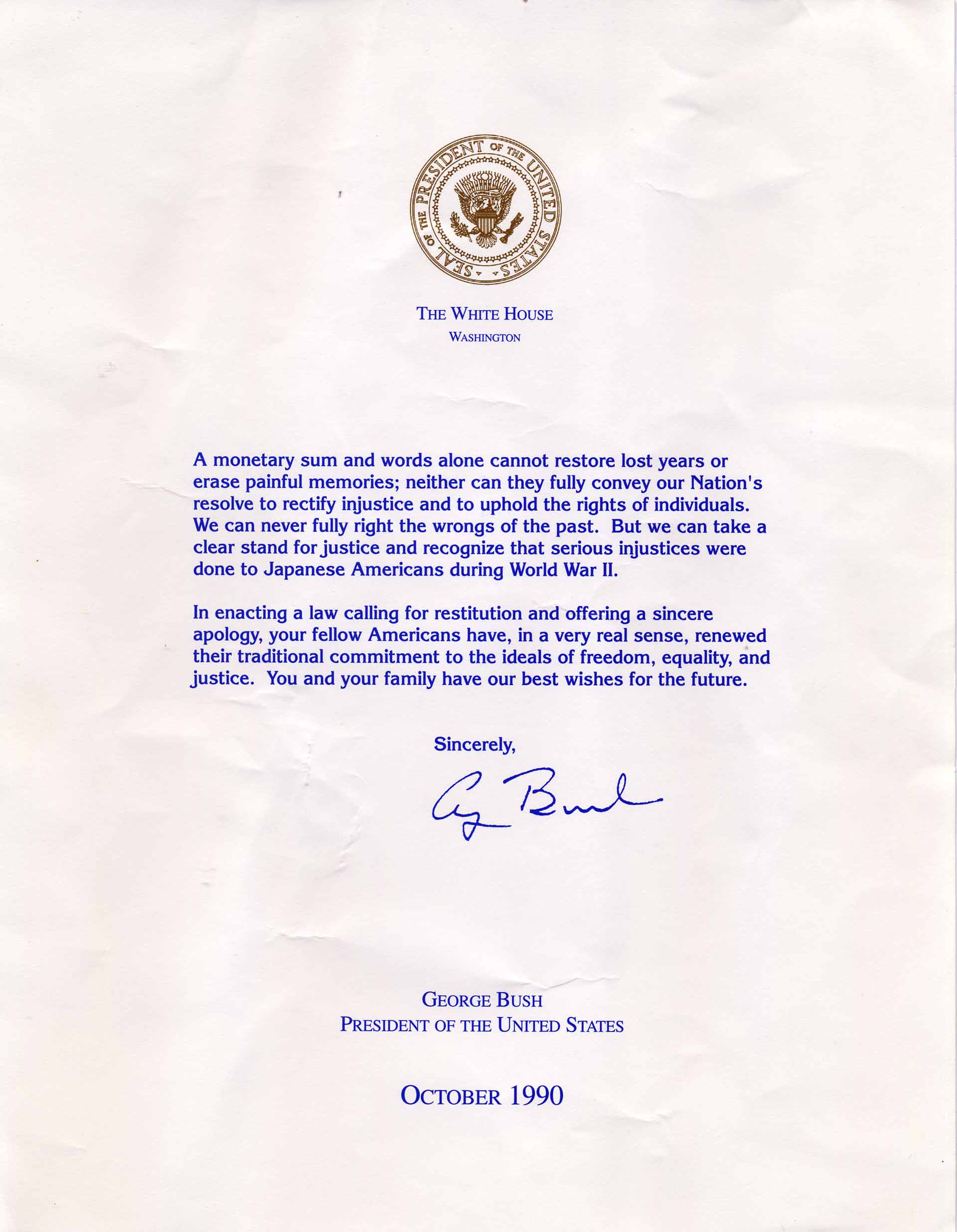

After hearing testimonies from hundreds of individuals, the federal commission issued a report titled Personal Justice Denied, which concluded that the wartime incarceration resulted not from “military necessity,” as the government argued at the time, but from racism, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership. The commission recommended monetary reparations and a formal government apology to all Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated.

For nearly a decade, hundreds of Japanese Americans and their allies of all races educated Congress about the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans and advocated for redress legislation.

Finally, on August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan approved the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 authorizing a formal government apology to Japanese Americans who had been wrongfully incarcerated during World War II, along with payments of twenty thousand dollars to each survivor.

More to explore

Video

05:39

Repairing a Wrong

Japanese Americans recount the challenges they faced after World War II, and the decades-long fight for reparations.

Reopening Cases

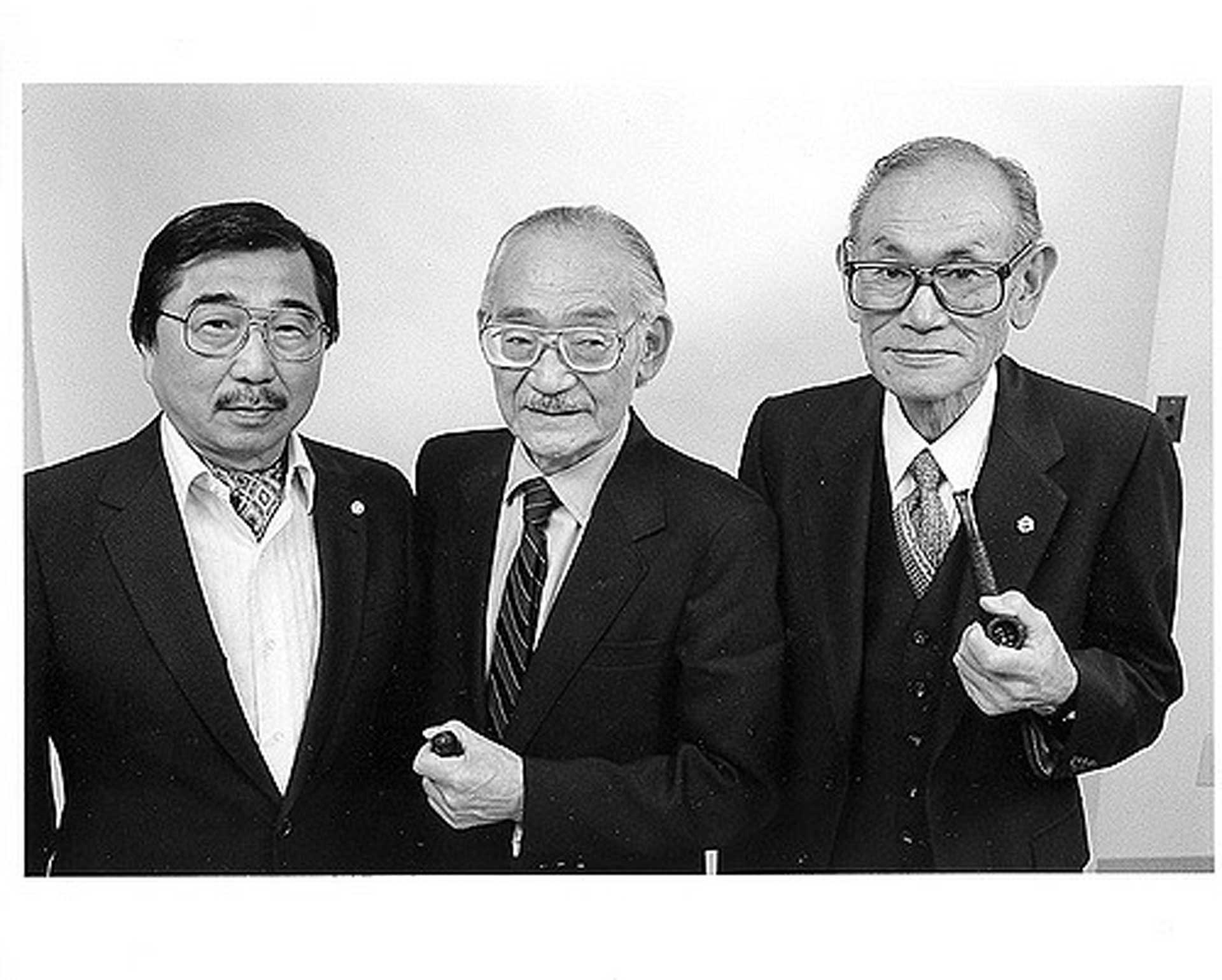

At the same time that the redress movement gained momentum, Min Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Fred Korematsu, three men who had lost their cases before the Supreme Court, challenged their criminal convictions for violating the government’s orders. They based their lawsuits on recently-discovered documents proving that, during World War II, government attorneys had intentionally suppressed evidence of Japanese American loyalty to the United States and had misled the Supreme Court into believing there was a military need to force them from their West Coast homes.

In the 1980s federal judges overturned the criminal convictions of all three men.

Image 45.01.15 — Forty years after the US Supreme Court ruled against Gordon Hirabayashi, Min Yasui, and Fred Korematsu, pictured here, federal judges in the 1980s overturned their criminal convictions. All three men subsequently received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor for civilians in the US.

Photo credit: copyrighted Bob Hsiang Photography. Metadata ↗

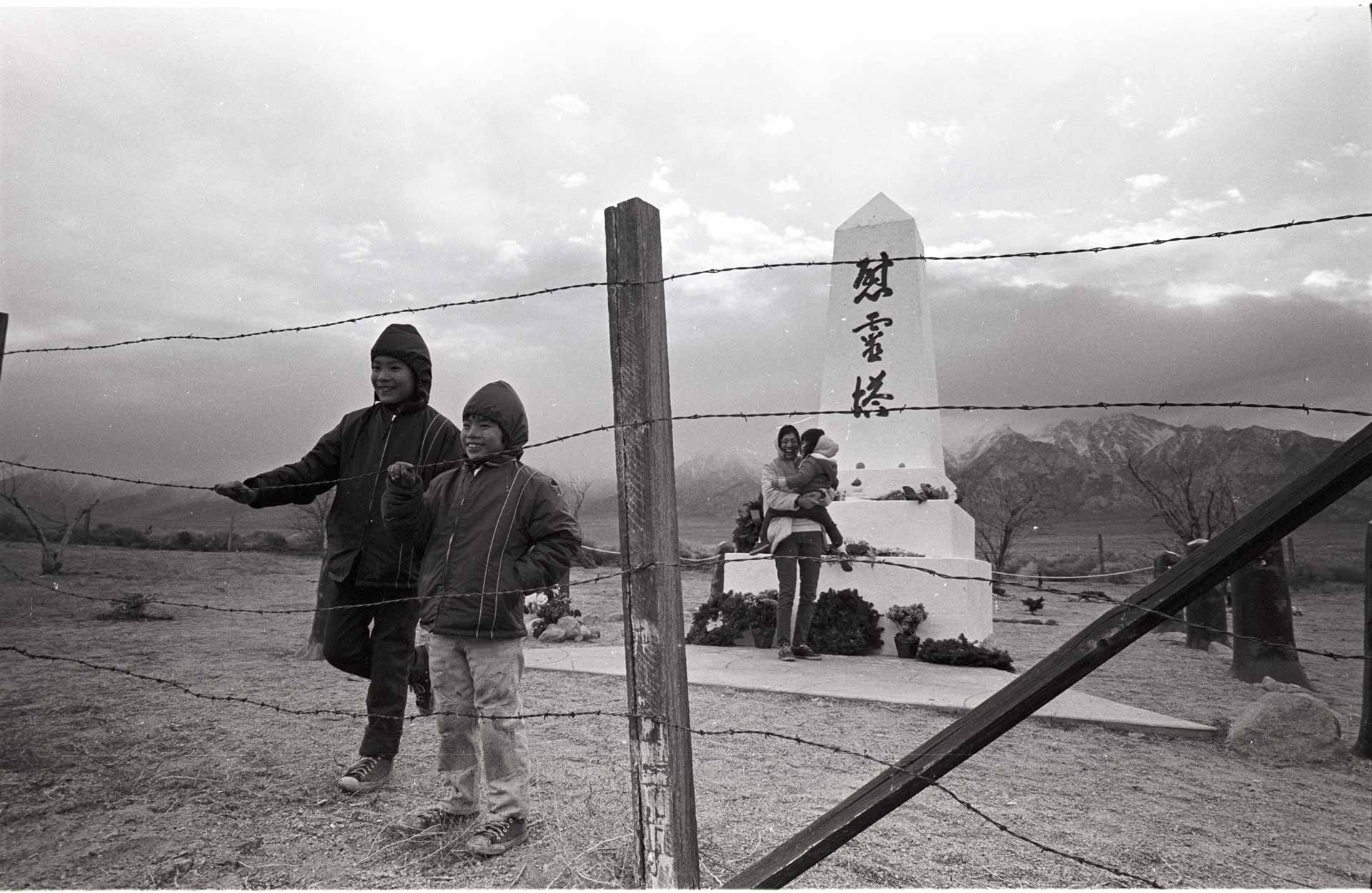

Remembering Incarceration Spurs Solidarity

Japanese Americans continue to fight for civil liberties, especially for other targeted groups during times of crisis.

Remembering the discrimination that they and their families experienced, many Japanese Americans have connected their community’s history with the prejudice and hatred directed at other groups, including Muslims, immigrants, and asylum seekers. Many Japanese Americans continue to speak out for the rights of people that the US government targets because of their religious beliefs, ethnic backgrounds, or immigration status. In doing so, they are carrying on the legacy of Japanese American activism during World War II and in the fight for redress.

More to explore

Glossary terms in this module

Alien Land Laws of 1913 Where it’s used

California passed the first law that prohibited “aliens ineligible to citizenship” from owning or leasing land, a law that targeted Americans of Japanese descent. From this point on until 1923, many states (Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming) across the US passed similar laws and restrictions.

assembly centers Where it’s used

Japanese Americans were temporarily detained or imprisoned in these facilities until more permanent incarceration camps were created by the War Relocation Authority. Many use the term “temporary detention centers” instead of “assembly centers” because it describes the US government’s true purpose, as well as the inhumane living conditions in these facilities. Japanese Americans were not simply gathered or “assembled” into these spaces.

Civil Liberties Act of 1988 Where it’s used

This federal law was formed as a result of the many activist efforts of Japanese American groups. All surviving American citizens and legal resident immigrants of Japanese ancestry who were incarcerated during WWII were given $20,000 and a formal presidential apology.

constitutional rights Where it’s used

Rights granted to Americans according to the US Constitution, such as the right to life, liberty, and property with equal protection of the laws. These rights cannot be taken away without due process.

Executive Order 9066 Where it’s used

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued this order giving US military leaders the power to designate regions of the country as military areas and to exclude anyone from those areas. Although Americans of Japanese descent were not specifically mentioned, this led to them to be mass incarcerated.

Fourteenth Amendment Where it’s used

This amendment to the US Constitution indicates that all people born on U.S. soil are American citizens and have the right to life, liberty, and property with equal protection of the laws. This amendment is especially significant in showing how Japanese Americans’ constitutional rights were violated.

Immigration Act of 1924 Where it’s used

A federal law that denied immigration to the US from Japan and other Asian countries (except the Philippines, which was then a US colony).

Japantown Where it’s used

Neighborhoods in cities in the Western United States, like San Francisco or Seattle, which served as the center of Japanese American life and culture before World War II.

Ozawa v. United States (1922) Where it’s used

A Supreme Court decision that determined Japanese people and other Asians were not allowed to become US citizens.

Personal Justice Denied Where it’s used

The title of the 467-page report issued by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The report concluded that the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans was not a military necessity, but instead resulted from racism, wartime hysteria, and failed political leadership.

redress movement Where it’s used

The term “redress” means to right a wrong or injustice, often through compensation. During the redress movement, many activist groups fought to gain reparations for Japanese Americans who were wrongfully incarcerated during World War II. These activists sought for the restoration of Japanese Americans’ civil rights, compensation for lost property, and a formal national apology.

reparations Where it’s used

The actions that a government or individuals take to offer an apology or give satisfaction for a wrong or injury.

War Relocation Authority (WRA) Where it’s used

The federal agency that managed the imprisonment of Japanese Americans. The word “relocation” inaccurately describes the action as simply moving or relocating to a new home. In reality, Japanese Americans did not have a choice and were forcibly removed from their homes.