Module 2: Larry Itliong

Did Filipino farmworkers achieve justice?

Modesto Dulay Itliong was born on October 25, 1913, in a small village in the Philippines named San Nicolas, in the province of Pangasinan. While Modesto’s nickname was “Larry,” for most of his life he lived true to his name, Modesto—which means modest and humble in Spanish. He loved books and was a voracious reader, but he received a limited formal education because there was not a high school in his village.

As a teenager, Itliong immigrated to America from the Philippines to pursue his dreams of becoming a lawyer, only to find himself becoming a farmworker and fierce activist by the time he was eighteen. He never became an attorney, but grew into a powerhouse labor leader who began the Delano Grape Strike of California. Partnering with César Chávez, he merged the Filipino union, Agriculture Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), with the Mexican association, National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), in 1966—the origins of the iconic United Farm Workers (UFW) union.

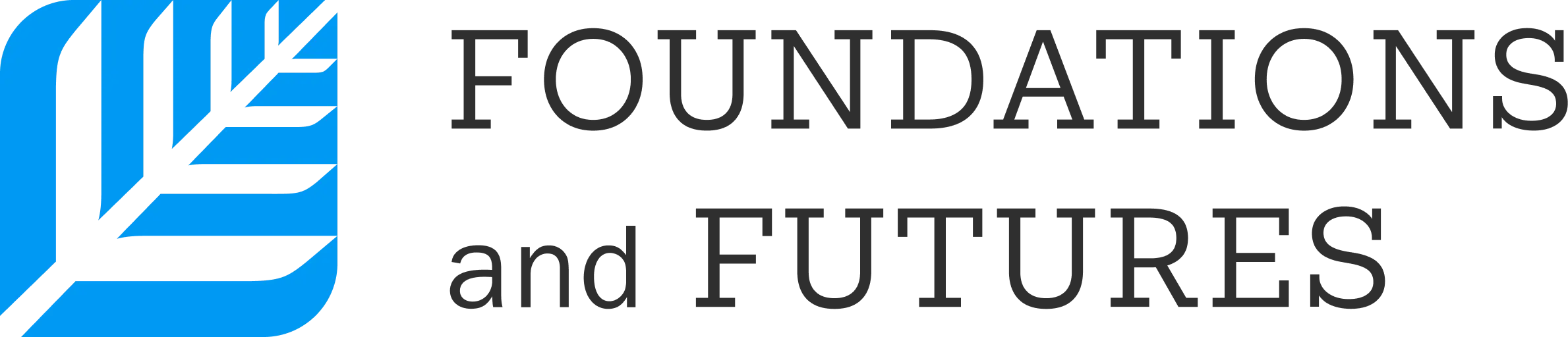

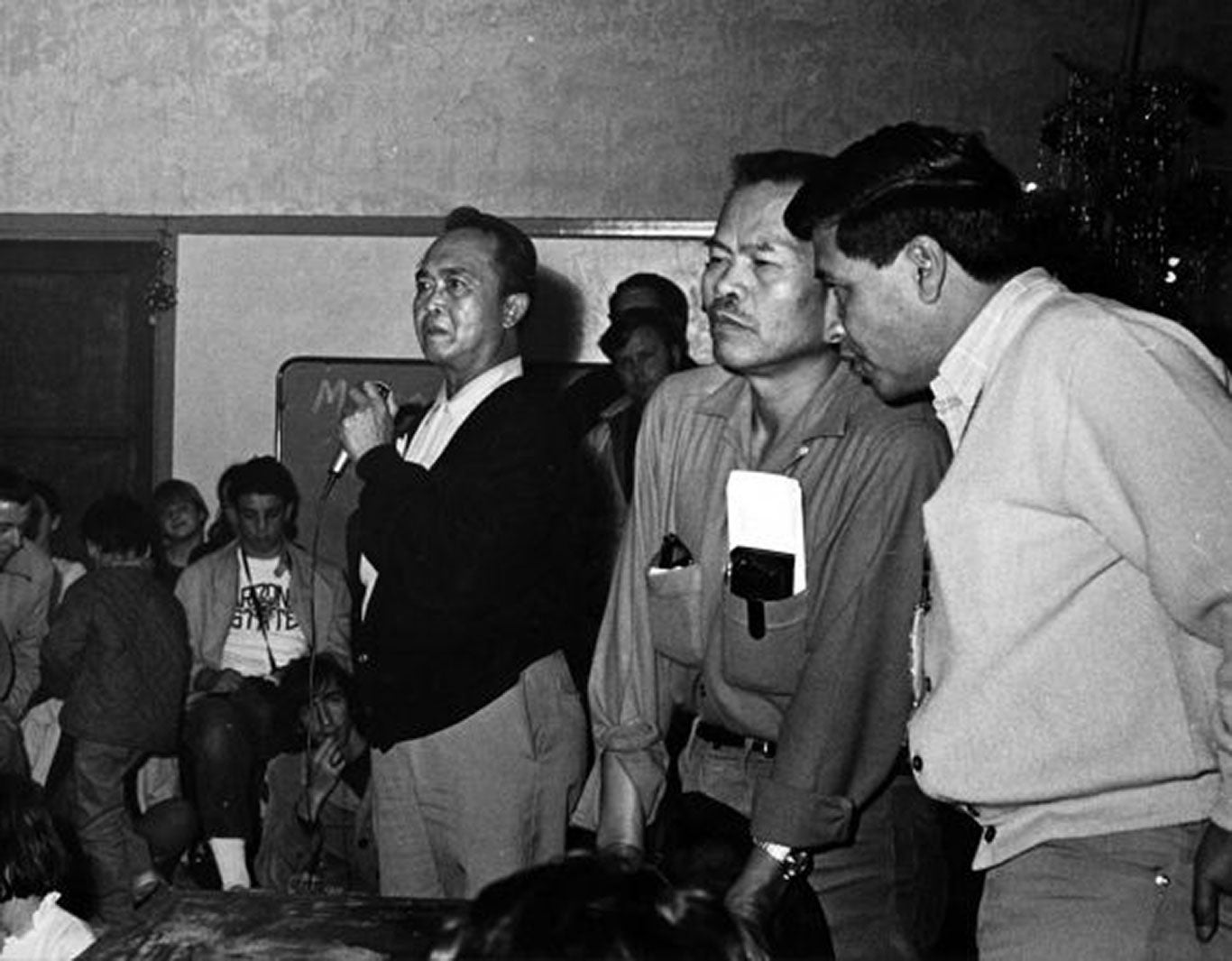

Image 46.02.01 — Larry Itliong, UFW Assistant Director speaking at an unknown event circa 1960s.

Courtesy of UFW Archives, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Metadata ↗

Who was Larry Itliong?

What was his contribution to the Farmworker Movement?

How did Filipinos practice solidarity through the United Farm Workers and the Delano Grape Strike?

Journey to the United States

As a boy in the Philippines, Itliong initially heard about the United States from teachers who would talk about the beauty and modernity of the country. A former neighbor who lived in the United States sent letters telling him to come to America and get an education there. And so when he was just fifteen years old, Itliong gambled on a card game and made enough money to buy a one-way ticket to the US. With just an elementary school education, and his charm and tenacity, he took the twenty-two-day boat ride to America on the steamship The Empress of Asia, in search of a better life. Age sixteen when he landed in Seattle, Washington, his dream was to go to college and become a lawyer.

Racism and Violence in the United States

Itliong’s plans to go to law school changed when he arrived in 1929. Racist laws barred him from receiving the education he wanted, and lawmakers banned Filipinos from practicing law in California. Like other Filipinos in the United States, he also experienced hardships such as poverty, segregation, and daily racist acts of violence. In addition, white communities would only hire Filipinos as farmworkers, cannery workers, busboys, cooks, and house boys. There was no way around these hurdles. Itliong made the difficult decision to let go of his dreams of getting a formal education. His only way of survival in the United States was to fight for the human rights of his fellow Filipinos.

Within six months of his arrival, he traveled the West Coast to work as a migrant farm and cannery worker. There, he learned of the five hundred white men beating, murdering, and chasing Filipinos out of Watsonville, California, known as the Watsonville Riots. The following week, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the Filipino Federation of America building in Stockton, another city in California where many Filipino immigrants resettled and worked. These two violent events in 1930 shaped the way Itliong and other Filipino farmworkers navigated life in the United States. They knew they had to create solidarity with one another to survive, despite coming from different provinces and speaking different languages. The only way to endure the racism and violence against their communities was to come together and demand their worth and right to a better life.

In addition to the anti-Filipino sentiments in the US, Itliong faced physical hardships, losing three fingers in an accident, earning him the nickname “Seven Fingers.” Itliong’s father wrote him to come home and offered to pay for his son’s education in the Philippines. But Itliong declined, and was determined to continue his path in the United States instead.

Organizing Farmworkers

Most migrant farmworkers during this time period were underpaid, treated badly, and had little control over their harsh and demeaning working conditions, as they did not have a union to represent them. Because of this, Itliong organized Filipino workers to demand the right to form a union, in order to negotiate better pay and labor conditions. By the time Itliong was nineteen years old in 1933, he organized cannery workers in Alaska and created the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union in Seattle. His role in the union started off as a delegate before taking on responsibilities as dispatcher, steward, and then later vice president. He also organized a union for sardine cannery workers in San Pedro and Wilmington, cities in Southern California. Itliong grew into a well-liked and highly strategic labor leader.

When he was a young adult, some of Itliong’s peers were storied organizers, writers and poets. He knew prolific author Carlos Bulosan from organizing in the fields, and Bulosan’s best friend, Chris Mensalvas, was a respected labor leader who built solidarity with the African American community starting in the 1940s. While Bulosan and Mensalvas were peers, Ernesto Mangaoang was a dear friend and mentor to Itliong. Ernesto Mangaoang was a gifted labor organizer and, like Itliong, had dreams of becoming an attorney but never finished his law school studies.

In 1948, the three labor organizers Mangaoang, Mensalvas, Itliong—and another strike leader, Cipriano “Rudy” Delvo—strategized the Stockton Asparagus Strike, one of the most significant agricultural strikes in California history. The strike drew four thousand Filipino farmworkers to walk off the asparagus fields. In the end, the Filipinos won and negotiated a pay raise.

Image 46.02.02 — In this image, Filipino farmworkers march through downtown Stockton, California during the 1948 Stockton Asparagus Strike. This strike was an important milestone in Filipino farmworker history because it provided firsthand experience that activated many Filipino workers to become more involved in labor organizing.

Courtesy of the Stockton Chapter, Filipino American National Historic Society. Metadata ↗

Despite this win, their paths as labor organizers were not easy. Mangaoang, Mensalvas, and several other Filipino union leaders, were arrested and threatened with deportation. During the Red Scare, a period in 1947–1954 when the US government promoted a widespread fear of Communism and leftist ideologies, Filipino union leaders were vilified and depicted as Communists. This government campaign became known as McCarthyism. At the same time, laws that limited the right to own property to only white people and criminalized interracial marriage made it impossible for Itliong and the Filipino community to thrive and live freely. It was also against the law for farmworkers to create their own union. With calculated strategy and union-backed attorneys, Ernesto Mangaoang’s court case made it all the way to the Supreme Court. He won his case and was able to stay in the US. Itliong continued to organize the community, becoming a legendary labor leader through countless cannery and agricultural strikes.

Delano Grape Strike

Following the success of the Stockton Asparagus Strike, Itliong led a predominantly Filipino union of farmworkers called the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), to mount one of the most important labor campaigns in American history in 1965. The AWOC was affiliated with and received funding from the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), which was formed from a 1955 merger and became the largest federation of unions in the US. Note that before the merger, the AFL had not previously accepted workers from nonwhite ethnic groups into its ranks.

The AWOC campaign sought to increase wages for grape workers in California. They began striking in Coachella and other parts of California, where Itliong and other Filipino farmworkers won their wage increases in May 1965. Itliong then headed north and began organizing workers for the larger Delano Grape Strike.

The Filipinos of Delano were greatly divided on whether or not to join the strike. There were more families in Delano by the mid-1960s. To go on strike meant that workers might not be able to provide for their family and children. On September 7, 1965, the farmworkers gathered at the Filipino Community Hall in Delano, and when manong and camp foreman Bob Armington made the motion to go on strike, other Filipino farmworkers followed suit and voted to authorize it. Filipinos demanded $1.40 per hour, 25 cents a box, and the right to form a union. The next day, over two thousand farmworkers cut the grapes off the vines in Delano, and then walked off the fields to pressure growers to negotiate a new contract.

One week later, Itliong invited César Chávez and his organization, National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), to join the strike. Itliong knew if he could unite Mexicans and Filipinos, the two largest groups of farmworkers, they would win. Itliong worked previously with NFWA leader Dolores Huerta in AWOC, and they had a long-running working relationship as union organizers. NFWA agreed to join the Filipinos of AWOC and went on strike. Filipino Community Hall became the headquarters of the strike, where Filipinos and Mexicans shared food, music, and solidarity for the first time. After one year, AWOC merged with the NFWA in 1966, creating the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, with Chavez as the director and Itliong as assistant director. Their leadership led to the iconic United Farm Workers (UFW) union, which was later officially accepted into the AFL-CIO in 1972.

Image 46.02.03 — Left to right: Pete Velasco, Larry Itliong, and César Chávez at Filipino Hall, Delano, California, Christmas, circa 1968.

Courtesy of UFW Archives, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Metadata ↗

During the farmworkers’ five long years of striking from 1965 to 1970, many people outside of agriculture took interest in the Delano Grape Strike, including Robert F. Kennedy. The former US attorney general and New York state senator at the time, Kennedy became an ally of the UFW. Itliong often wrote to Kennedy to keep him abreast of the happenings of the union. In fact, Itliong frequently wrote letters to those who were politically well-connected, such as former US senator and vice president Walter Mondale. Because of his work as a seasoned organizer who had previously won large union campaigns, Itliong was well-respected by politicians, community leaders, and union membership.

Image 46.02.04 — Left to right: Andy Imutan (one of the original strikers), Dolores Huerta (co-founder of the UFW), Larry Itliong, and Robert Kennedy at a rally in Delano, California, March 10, 1968.

Courtesy of UFW Archives, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Metadata ↗

Itliong was also tasked to fundraise for the UFW, asking those in positions of power for funding for the Delano Grape Strike and became the international coordinator of the three-year consumer boycott of table grapes. By 1970, the UFW won the Delano Grape Strike, which had grown to become an international campaign placing a spotlight on farmworkers and their right to join unions, and the community power wielded by workers. With César Chávez, Itliong signed new union contracts with Delano grape growers on July 29, 1970.

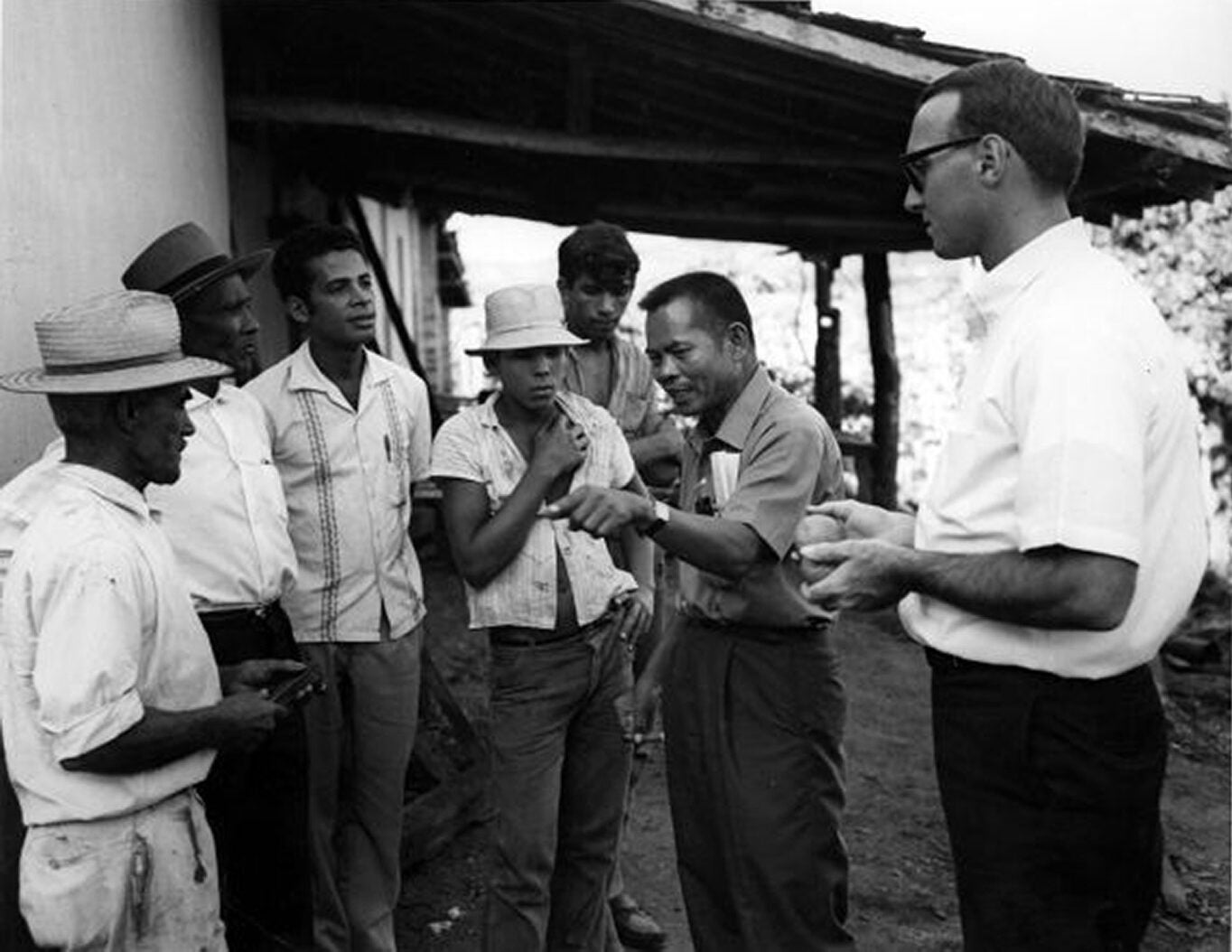

Image 46.02.05 — Larry Itliong speaks to Brazilian farmworkers in Brazil, circa 1960s. Itliong traveled to Brazil and Chile to organize workers to be in solidarity with other labor movements across the globe.

Courtesy of UFW Archives, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Metadata ↗

The Fight Continues

After their great victory, Itliong continued his labor activism because the work was far from done. However, divisions arose between members of the new union. To Filipino farmworkers, the UFW’s new hiring policies felt unfair, and they felt betrayed and ignored when César Chávez made decisions without their input. There was also tension between Itliong and Chavez, who did not always agree on the union’s principles and strategies. Itliong believed in a national union for farmworkers, but he struggled with the decision to stay in the UFW. He wrote a list of pros and cons. After fighting for so long, he wanted clarity on where his strategic and political skills could make the most difference and decided to resign from the UFW on March 31, 1971.

Itliong later created a new campaign teaching Filipino American college students their Philippine and American history, speaking at universities, colleges and conferences throughout the West Coast. While he was never able to get a formal education, Itliong dedicated the rest of his life to the next generation as an educator and speaker. He also oversaw the initial planning and design work on Agbayani Village, which provided housing for retired Filipino/a farmworkers. The village was opened at the former UFW headquarters, Forty Acres, in Delano, California.

On February 8, 1977, Itliong died from ALS at the age of 63. At the time of his death, Itliong and the Filipino farmworkers had been largely written out of California farm labor history. It was not until then-California Assemblymember Rob Bonta, created two important state bills in 2013–2015, Assembly Bill 123 and Assembly Bill 7, calling for this important history to be formally recognized. All California public schools were required to teach students about the contributions of Filipinos in the farm labor movement.

In 2018, the organization, Labor’s International Hall of Fame, inducted Itliong into their list of labor leaders, honoring his legacy and memory. In 2021, California Governor Gavin Newsom inducted him into the California Hall of Fame and proclaimed October 25, Itliong’s birthday, as Itliong Day, not just for public school students, but for the entire state of California. At present time, California schools and parks are now being named after Itliong, and the Filipino American contribution to American and labor history are now more increasingly recognized throughout the US.

More to explore

Video

22:20

Journey for Justice

Read Aloud of targeted pages of Journey for Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong, By Dr. Dawn Mabalon with Gayle Romasanta and Illustrated by Andre Sibayan. Purchase the book “Journey for Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong” at www.bridgedelta.com or amazon.com. Download the free curriculum resource guide at www.bridgedelta.com or pepsf.org.

Glossary terms in this module

Agbayani Village Where it’s used

Agbayani Village was a housing facility built in 1974 for the elderly farm workers who could no longer work or wished to retire. Students and activists from across California came to help raise money and build the facility for Filipino and Chicano elders. Agbayani Village is named after Paulo Agbayani, one of the Filipino farm worker elders who participated early in the Delano Grape Strike but died of a heart attack while picketing on the front lines.

McCarthyism Where it’s used

Also known as the Red Scare, McCarthyism is a paranoia about Communism that was part of American society in the 1950s, named after Senator Joe McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin.

poverty Where it’s used

A condition characterized by a lack of access to basic needs such as food, housing, and healthcare that is often caused by systemic inequalities, such as discrimination and lack of access to educational and economic opportunities.

strike Where it’s used

A deliberate plan to stop working as a collective form of protest against an unjust employer or employment practices and/or conditions.

unions Where it’s used

An organization formed by workers, typically from the same industry or company, for the purpose of maintaining and improving the conditions of their workplace.