Module 3: Filipinas in the Filipino Farmworker Movement

Did Filipino farmworkers achieve justice?

Filipinas were a strong and essential part of the farmworker movement. Long before the movement gained national momentum, these women were a constant source of aid in the farmworker communities that formed from the 1920s–1970s. Despite their smaller numbers, with one Filipina for every twenty Filipinos from 1903 to the 1930s, Filipinas worked as labor organizers and cultural bearers of farmworker communities across rural California.

How did Filipinas participate in the Filipino farmworker movement? What roles did Filipinas have in the farmworker movement?

How was their experience similar and different from men?

What types of justice did they seek? What impact did Filipinas have in the farmworker movement?

The Manang Generation

The handful of Filipinas that first immigrated to the United States from the 1910s to the 1950s were known as the manang generation. The term “manang” means older sister in the Ilocano-Philippine dialect and is a term of endearment for Filipina elders. The majority of these women were wives that accompanied their families to help work in the fields and orchards of California as a means of income to support their families in the Philippines. Once in the United States, Filipinas established their own community networks and organizations, such as the Filipino Women’s Club, to help attend to the needs of their small farming communities. Their fundraising, event organizing, and community projects helped to create stable farming communities for the Filipino farmworkers to rely on.

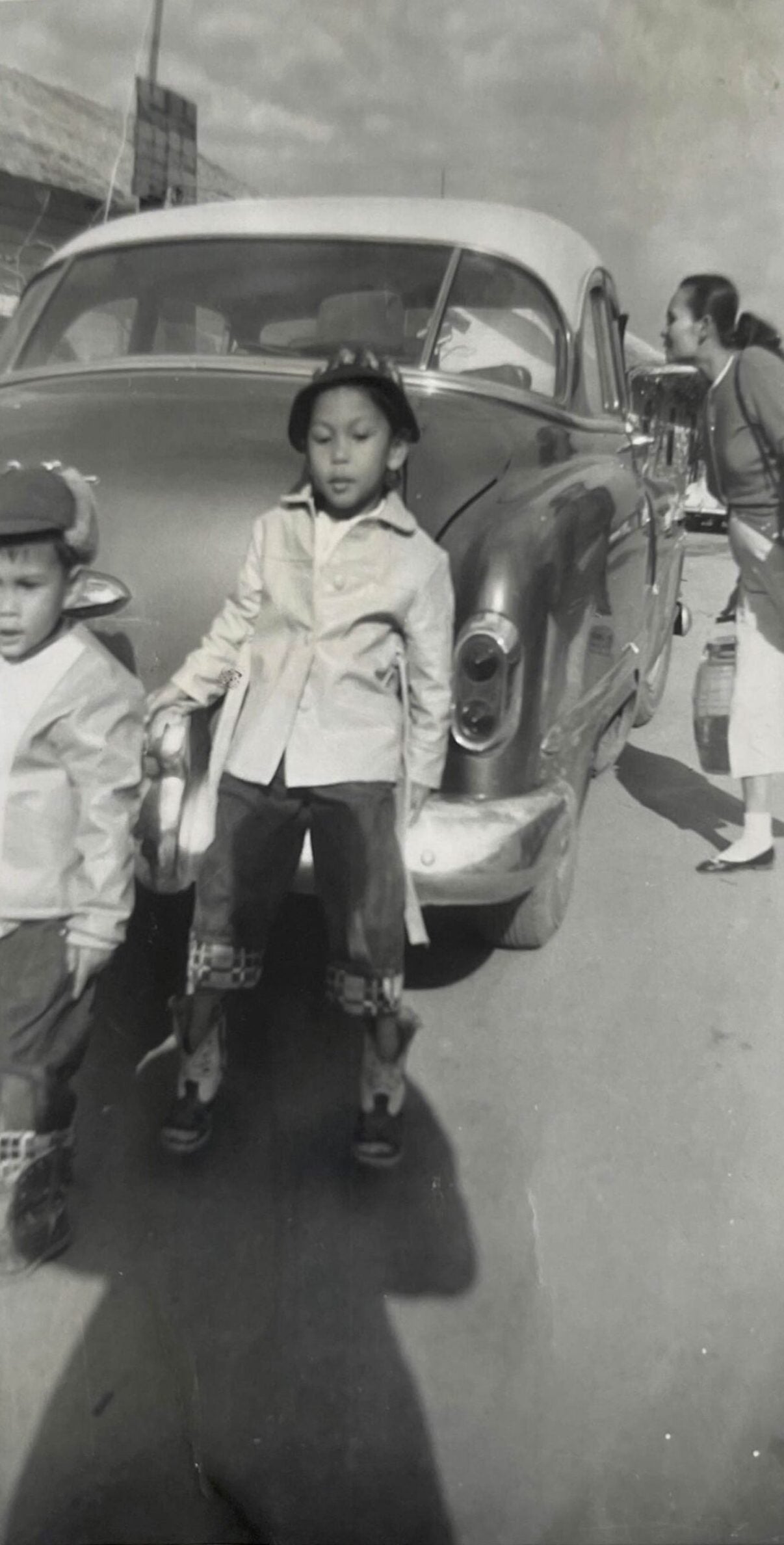

Like many manangs, Cornelia Delute is remembered for her roles in the Delano community. She cooked and prepared food and snacks for the field workers. The time-intensive Filipino desserts she prepared for the manongs included bibingka, biko, cassava cake, and suman. Without any childcare benefits, Delute, like other Filipina farmworkers at the time, took her children with her into the fields as she sold her homemade goods to the manongs (a term of endearment for Filipino elders), who saw such snacks as nostalgic reminders of their homeland. As a working mother who worked side by side with the manong farmworkers, Cornelia Delute saw the value in a strong union. She and her husband, Heriberto Delute, both became strong supporters of the United Farm Workers (UFW), and she continued to work in the grape fields and carrot-packing sheds until her late seventies.

Image 46.03.01 — Cornelia Delute speaking with local farmworkers as her children in the photograph pose in front of the camera. Cornelia carries the container with her homemade binangkal (sesame bread) and suman (rice cake). Delano, circa 1950s.

Courtesy of the Delute Family. Metadata ↗

Cornelia Delute, like many of the manangs, utilized her domestic skills to support her family and community. Other Filipinas worked at the labor camps, also known as “campos,” where the manongs lived. Filipinas at the campos had many jobs and worked as cooks, nurses, cleaners, laundresses, seamstresses, and even helped to manage the annual budget of the camps if their husbands were the foremen or camp owners. Most importantly, Filipina workers were essential hosts that oversaw camp operations, served hearty Filipino meals, and helped keep up the morale of farmworkers after twelve-hour workdays.

Educated Women

The majority of the Filipinas who came to the United States from the 1920s to the 1950s were college educated. Many of the manongs who arrived and worked in the fields during the early twentieth century were middle- to lower-class and did not have a full education, making tasks that required heavy reading and writing difficult. As a result, the Filipinas who worked at the labor camps, in the fields, and in the packing sheds regularly helped the manongs with their paperwork for citizenship, taxes, and other legal documents.

Despite their educated backgrounds, some Filipina farmworkers still faced obstacles when working toward advancing their careers. Natividad “Naty” Ballesteros Edillor received her degree in education in the Philippines, but upon arriving in California, found that she had to acquire another teaching credential in order to teach at elementary schools in the United States.

Image 46.03.02 — Natividad Ballesteros Edillor (kneeling, second from left), with her female coworkers at Lucas Camp with camp foreman Bob Armington (standing, fourth from left), ca. 1960.

Courtesy of the Edillor Family and Delano. Metadata ↗

Her son Alex Edillor remembers, “She tried to pursue her teaching credential but gave up due to the hardship of attending college at night (commuting by bus thirty miles each way) while working during the day and keeping a household of four. She worked alongside her husband and the manongs harvesting produce (grapes/carrots) in and around Delano until her retirement. [Mom] used her education as a ‘go-between’ for the manongs who wished to send letters, money, and gifts to their families in the Philippines. She participated in the grape strike, supported her Fil-Am community and family as one of its anchors, and lived to be 92 years old!” 1

Essential Labor of Filipinas

The women of these communities took on a range of responsibilities to support their fellow farmworkers. Susan Aremas, a daughter of Filipino farmworker Ricardo Aremas described the manangs as, “supportive wives [who] would help the manongs do their taxes, acted as matchmakers for the single manongs, and were the best nurses! They would take care of them when they were too ill from their work on the farms because they were overworked and exposed to DDT (a harmful synthetic insecticide to humans). The manongs couldn’t afford to go to the hospital, and the women acted as their nurse, sister, and mother to them.” 2

Susan Aremas’s mother, Sherry Estojero Aremas, was a community organizer who participated in the Filipino Women Club’s activities to help elderly Filipino farmworkers. Many manangs and their children helped the elderly manong farmworkers file their union memberships and register with the UFW, securing much needed healthcare benefits and protected wages.

Image 46.03.03 — Baptism for Susan Aremas (center being held by her aunt), and her mother Sherry (left of her), in the Salinas Labor Camp, circa 1940s. Two or more families at the camps would often share one small bunkhouse.

Courtesy of the Aremas Family. Metadata ↗

Even when essential utilities like warm water and electricity were cut off at the campos as a means to threaten farmworkers and prevent striking, many Filipinas continued their roles as best they could to keep the strikers fed. Throughout the movement, Filipinas would organize and help schedule the union meetings at the Filipino Community Hall in Delano. Alongside other Chicana, or Mexican American, union members, they would prepare the majority of the meals for the union meetings in the Hall’s kitchen.

Filipina farmworkers were also mothers, and many felt at a loss when honoring the strike by not working in the fields. As breadwinners in the family, some felt that if they did not work by participating in the strike, then their families would also starve. Some chose to continue working in the fields in order to feed their children, and oftentimes found other ways to help the strike by housing or feeding the Filipino and Chicano union members.

Image 46.03.04 — Labor camp life in the fields, with Raymund Pacis Barney (center back). Lucena L. Barney (center front) with John L. Barney, Filomena (Navaro) Fernandez (married to Zuilo Fernandez). Delano, 1940s.

Courtesy of the Barney and Simon Families. Metadata ↗

In the more traditional households that participated in the movement, Filipinas were not often seen as the faces of the union. Rather, they were expected to take on all of the responsibilities of family care while also trying to make ends meet to support their household’s income. This burden where women take on both unpaid family duties and childcare on top of paid labor outside of the home is known as “double day” work—a concept that women in the labor movement grew increasingly aware of in the twentieth century. In addition to their domestic work, Filipinas and Chicanas regularly marched alongside the manongs and provided food and water to the strikers in the fields and on the roads. There, they faced various forms of violence and intimidating threats from local police and vigilante justice squads hired by white farm owners and growers.

Filipinas in the Fields

For Filipinas who worked in the fields and packing sheds, unionizing and striking meant better opportunities to feed and house their families, all guaranteed through union contracts that advocated for safer working conditions and livable wages. Depending on whether they worked in the packing sheds or the fields, Filipinas earned on average between $0.95 and $1.30 an hour during the 1960s.

Filipinas were especially vulnerable to the dangerous working conditions in the fields. They faced sexual harassment, were paid half than what the men were paid, and suffered greatly from pesticide exposure, all issues that migrant women farmworkers continue to face today. With no childcare, Filipinas would bring their children to work with them. The limited schools available to farmworkers’ children and the poor housing provided at the labor camps left little room for farmworker families to escape poverty. Finding accessible transportation to schools was another consistent barrier that farmworker families contended with.

Furthermore, many children worked in the fields alongside their parents to help their families make ends meet. Thus, mothers also saw the farmworker movement as an opportunity towards livable wages that could support their families and potentially end child labor. Such a movement, co-led by women farmworkers, represented a brighter future for all members of farmworker families.

Filipinas in the Farmworker Movement

The majority of Filipinos who immigrated prior to World War II were single male laborers. During the 1933 court case of Roldan v. Los Angeles County, Filipinos were legally defined as falling under the racial category of “Malay” and therefore considered nonwhite. Due to their legally assigned nonwhite status, Filipinos were not allowed to enter into marriages with white women. With Filipinas immigrating to the United States in far fewer numbers prior to World War II, Filipino farmworkers married Chicana, Native American, Asian, and Black women. Many of the early families of the rural Fil-Am communities were thus of mixed heritage.

Lorraine Agtang was an instrumental figure in the farmworker movement. She was born in a labor camp near Delano, California in 1952. Like many of the children of the manang and manong generation, she was of mixed Mexican and Filipino heritage. Her mother, Lorenza Agtang, was born in Chihuahua, Mexico. Her father, Platon Agtang, was a migrant worker from Cavite Province, Philippines. He worked in the sugar fields in Hawaiʻi, the canneries in Alaska, and the farmworker circuits throughout Central California.

Lorraine Agtang’s early exposure to farm labor activism occurred when her family left the fields of Giumarra Farms in support of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) during the 1965 Delano Grape Strike. Agtang would continue getting involved with the United Farm Workers (UFW), from working at the hospital clinic located at the UFW’s Forty Acres headquarters, to serving other organizing roles.

The Farmworker movement coincided with the multiple civil rights movements across the country, including the fight for Ethnic Studies and the Asian American movement. Many Filipinas who were part of these multifaceted student activist projects at their college campuses were the children of farmworkers who rallied and marched in protests.

Other college-age Filipinas across California, like Lorraine Agtang, felt inspired to join the movement after hearing leaders like Philip Vera Cruz or Larry Itliong speak at their local community centers or town halls. They learned about the value of nonviolent protesting, which the UFW practiced. In 1973 and 1974, some Filipina student activists traveled to Delano to volunteer in building Agbayani Village, a retirement home for elderly Filipino farmworkers.

Image 46.03.05 — As the United Farm Workers resumed strike activities against Delano’s table grape growers, Filipino American UFW members rejoined their union brothers and sisters on the picket lines, Delano, 1973.

Courtesy of Lorraine Agtang and the Welga Digital Archives. Metadata ↗

Preserving Farmworker History

Filipinas like Lorraine Agtang also worked at Agbayani Village as the facility’s very first managers. While working at Agbayani Village, Agtang got to know many of the Filipinos who participated in the 1965 grape strike, including the former UFW Vice President Philip Vera Cruz, known as the great philosopher of the movement. Agtang would continue to serve the UFW as an organizer during the 1973 strike.

Like many of the Filipinas who participated in the Farmworker movement, Agtang’s experiences as an activist continue to shape and inform her service to the Filipino American community. Agtang and many of the children of the manang and manong generation have continued to preserve, promote, and teach the history of Filipino Americans in the farmworker movement so that the next generation may learn of their struggles, accomplishments, and contributions.

Author’s note: The families who donated or shared their testimonies for this module are Filipino families of Delano, including the family photographs and talk stories of the Delute Family, Edillor Family, Barney-Simon Family, Aremas Family, Bonta Family, and Armington Family.

Glossary terms in this module

activism Where it’s used

The actions and philosophies that people practice to create positive change in their communities.

Agbayani Village Where it’s used

Agbayani Village was a housing facility built in 1974 for the elderly farm workers who could no longer work or wished to retire. Students and activists from across California came to help raise money and build the facility for Filipino and Chicano elders. Agbayani Village is named after Paulo Agbayani, one of the Filipino farm worker elders who participated early in the Delano Grape Strike but died of a heart attack while picketing on the front lines.

manang Where it’s used

A term of endearment for Filipina elders. A term from the Philippine-Ilocano dialect meaning “older sister.” Because a vast majority of the Filipina/o/x population that made up the farmworker movement were from the Ilocos region of the Philippines, Ilocano terms were used regularly among Fil-Am community members.

migrant worker Where it’s used

Someone who moves from place to place, often across national borders, to work temporarily or seasonally.

poverty Where it’s used

A condition characterized by a lack of access to basic needs such as food, housing, and healthcare that is often caused by systemic inequalities, such as discrimination and lack of access to educational and economic opportunities.

strike Where it’s used

A deliberate plan to stop working as a collective form of protest against an unjust employer or employment practices and/or conditions.