LABOR & ACTIVISM OF FILIPINO FARMWORKERS

Authors

Author

Robyn Rodriguez

Robyn Magalit Rodriguez is best known for her role as a scholar and Professor Emerita of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Davis as well as founding director of the Bulosan Center for Filipinx Studies. She established the Amado Khaya Initiative as a way of honoring and continuing the legacy of community organizing and activism led by her eldest son. A mother, Dr. Rodriguez has two sons, Amado Khaya and Ezio, who is in grade school and is learning how to be a farmer on Remagination Farm, a property of Dr. Rodriguez and her husband, Joshua Vang.

Author

Catherine DeGuzman

Catherine Anne Sahagun DeGuzman served as a Student Justice Advisor and Ambassador for the Bulosan Center for Filipinx Studies, which has transitioned to the Amado Khaya Initiative, a grassroots organization dedicated to preserving and disseminating knowledge about the Filipinx experience. At UC Davis, Catherine worked as a Student Assistant and Peer Advisor in the Asian American Studies Department. These roles fueled her passion for addressing issues faced by Asian Americans and other marginalized groups through Ethnic Studies, research, grassroots organizing, and advocacy. Catherine earned her bachelor’s degree with honors in Asian American Studies from UC Davis.

Did Filipino farmworkers achieve justice?

Carlos Bulosan was a Filipino American writer and activist best known for his semi-autobiographical novel, America Is in the Heart. Born in the Philippines in 1913, he immigrated to the United States in 1930 at the age of seventeen. During this time, the Philippines was a colony of the United States. Filipinos were allowed to travel to the United States despite other anti-Asian immigration laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Gentlemen’s Agreement, which prohibited the immigration of Chinese and Japanese people. Once in the United States, Bulosan worked as a migrant laborer, traveling across the country to work on farms and in canneries.

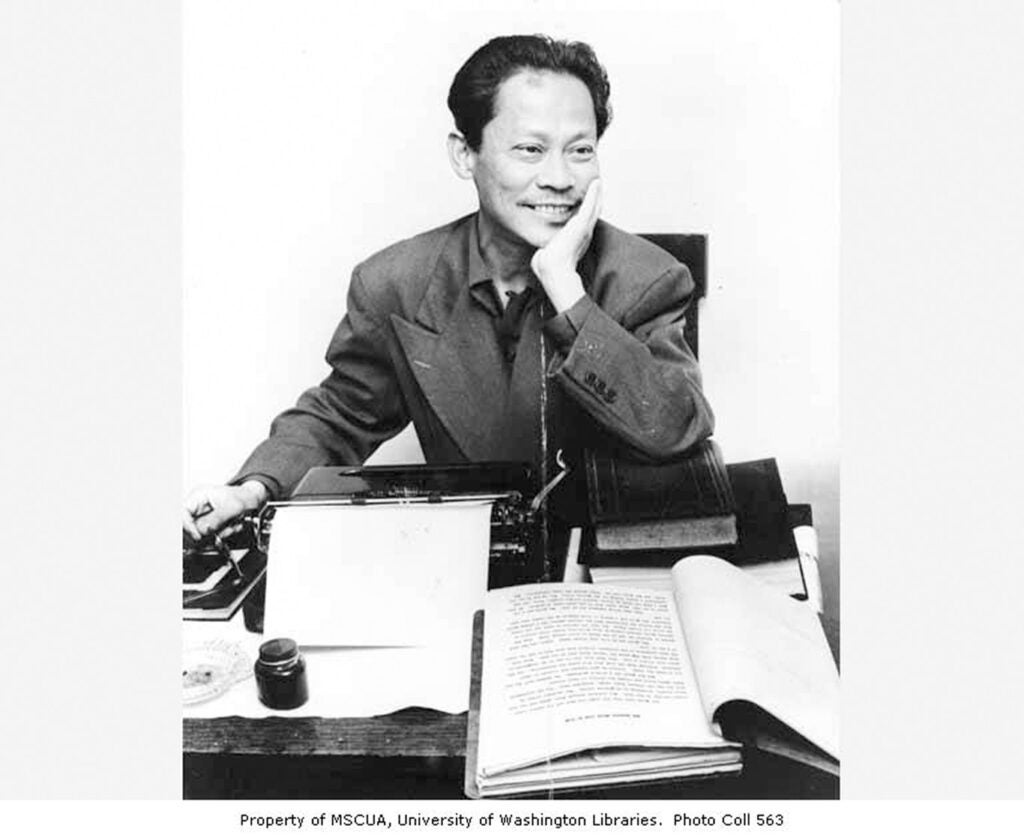

Image 46.04.01a — Carlos Bulosan, pictured at his desk with typewriter and manuscripts, c. 1955 in Seattle, Washington, continued to write in his final years despite facing censorship and isolation as a consequence of his activism.

Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Metadata ↗

1 of 5

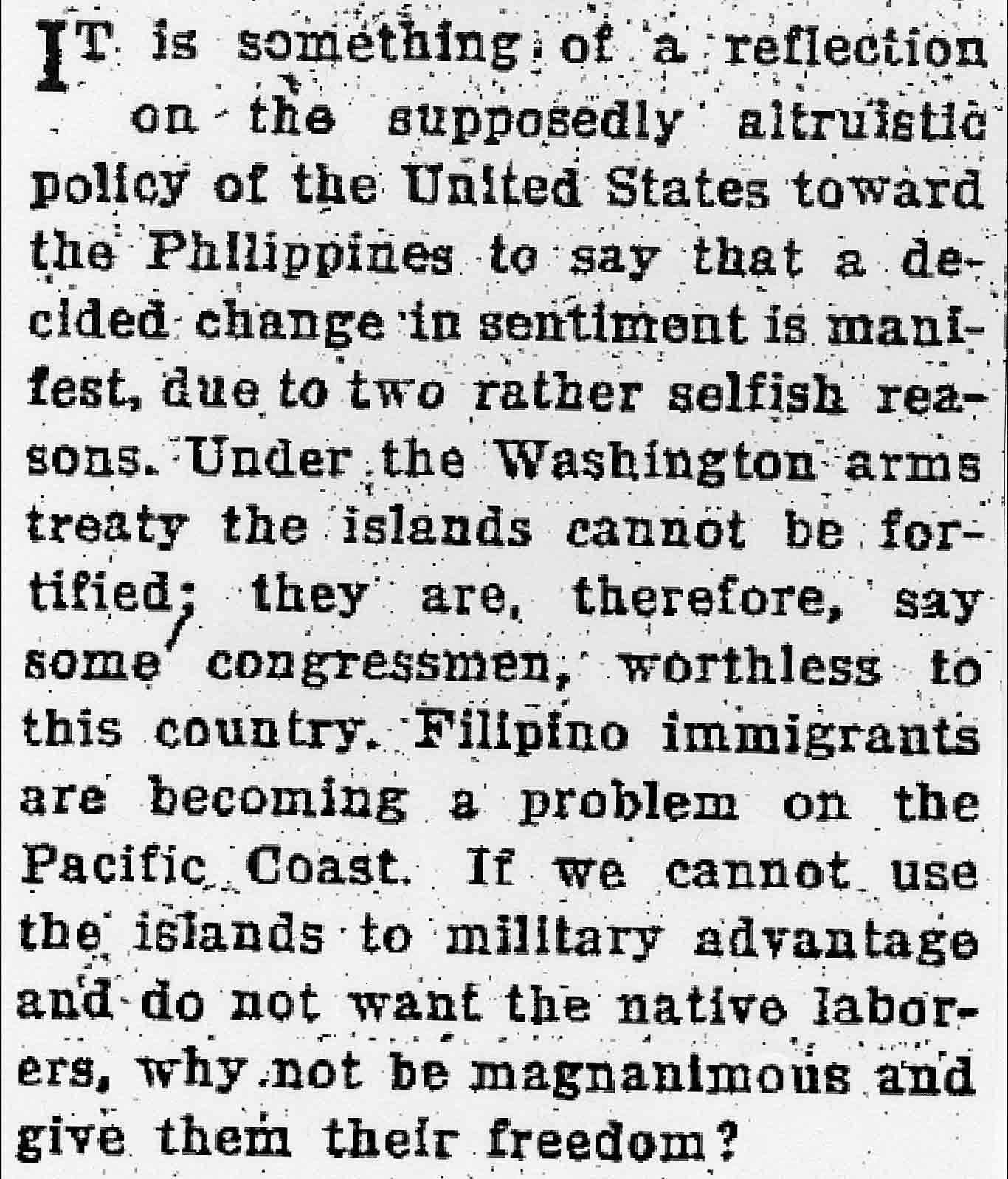

Image 46.04.01b — Carlos Bulosan, pictured at his desk with typewriter and manuscripts, c. 1955 in Seattle, Washington, continued to write in his final years despite facing censorship and isolation as a consequence of his activism.

Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Metadata ↗

2 of 5

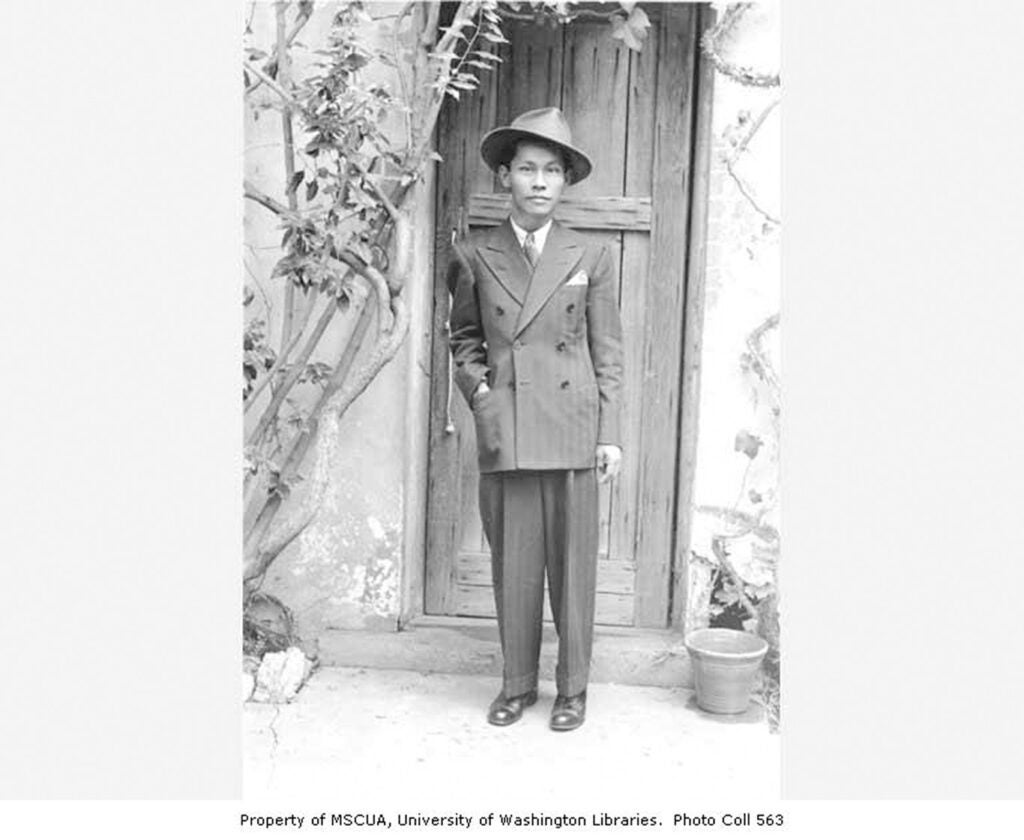

Image 46.04.01c — An anonymous Filipino man working to process fruit, circa 1930, illustrates the hard labor and low wages that many Filipino immigrants faced during this time in the United States.

Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library. Metadata ↗

3 of 5

Image 46.04.01d — Filipino salmon processing workers, known as “Alaskeros,” faced a difficult seasonal migratory lifestyle, spending summers in Alaska, and then working in the “farm factories” of California and eastern Washington during other seasons, to support themselves and their families.

Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Metadata ↗

4 of 5

Image 46.04.01e — The county’s first Filipino-led Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union Local 37 fought for fair treatment and rights, shaping the 1950s labor movement. Carlos Bulosan and Chris Mensalvas, former union leaders, alongside fellow workers in this photo.

Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Metadata ↗

5 of 5

How do Carlos Bulosan’s writings describe the Filipino farmworker experience?

What does his book teach about Filipinos, labor, and activism?

How does Carlos Bulosan’s writing challenge dominant narratives about immigration, racism, and the American Dream in the United States?

The Stark Reality of Farmwork

Bulosan was part of a pioneering generation of Filipinos—most of them Ilocanos and Visayans from farming families in the provinces—who struggled to survive as migrant workers in the United States, toiling in the fields across the West Coast and the Midwest and under brutal contracts on Hawaiian sugar and pineapple plantations. Between 1898, when the Philippines formally became a US colony, and World War II, over one hundred thousand Filipino immigrants, mostly men, came to Hawaiʻi and the United States. During this colonial period, American teachers bragged of the incredible educational opportunities awaiting Bulosan and other Filipinos. As one migrant worker recalled, teachers told their students that they could “pick gold up from the streets in America.” But the stark reality of their lives in the United States could not have been further from this fantasy. Due to the Great Depression, migrant workers’ pay was reduced to a dollar a day. The economic crash and the exploitation of Filipino laborers through low wages made it impossible for them to save enough money to return home rich, or even at all.

In addition to their low wages, Filipino farmworkers were severely mistreated and abused. Bulosan, like many of his generation, fought back as a labor organizer and an advocate for Filipino citizenship rights. In her book, Little Manila Is in the Heart, historian Dawn Bohulano Mabalon writes about Bulosan:

“An ardent leftist political activist and union organizer who believed that Filipinos should be allowed to become citizens (at the time, Filipinos and other Asians were barred from naturalization), Bulosan along with Filipino immigrant Claro Candelario, founded the Committee for the Protection of Filipino Rights, which lobbied Congress in the 1930s for Filipino citizenship rights. With Candelario, Bulosan moved to Stockton in 1939 to organize for the citizenship campaign. Though Bulosan also had occasional residencies in Seattle and Los Angeles, he lived in Stockton intermittently through his entire life, making Stockton’s Little Manila one of his main residences (for years, he received mail at 110 S. El Dorado Street, which was a Filipino-owned barbershop, and at 50 E. Lafayette Street, Ambo Mabalon’s Lafayette Lunch Counter, according to his papers at University of Washington).” 1

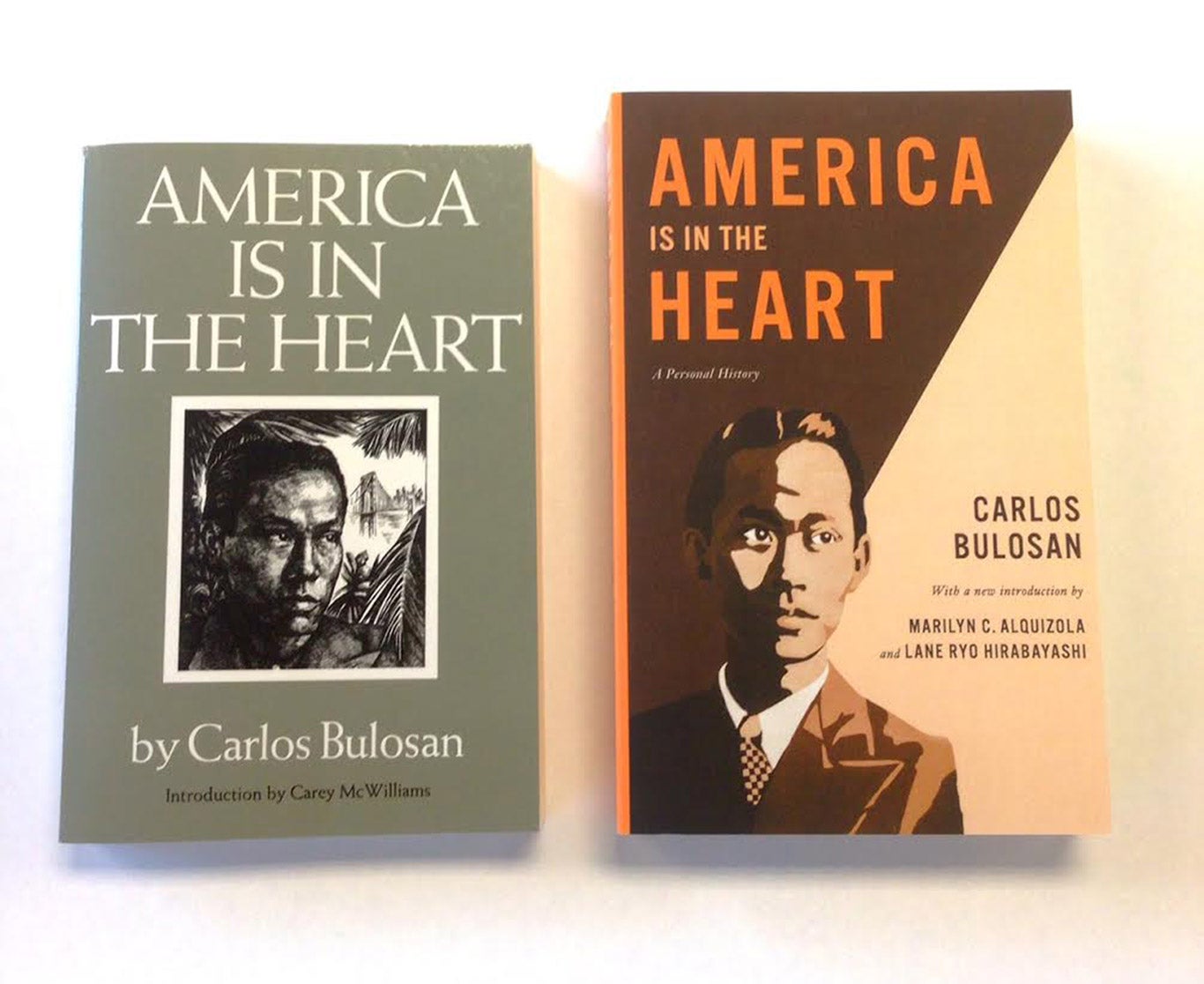

Image 46.04.02 — Pictured here is the cover of Carlos Bulosan’s America Is in the Heart. On the left is the 1973 edition and on the right is the 2014 edition.

University of Washington Press Blog. Metadata ↗

Bulosan’s Writing as Activism

Although Bulosan was involved as a community organizer, he always dreamed of being a writer. In the early 1930s, Bulosan, who was mostly self-taught, began to write and share his poetry, essays, and short stories in the US. He published his writings in Filipino American newspapers such as the Philippine Journal and the Philippine Examiner. By the 1940s he continued to publish in Filipino American newspapers based in California, such as the Philippine Commonwealth Times, as well as in major national outlets like The New Yorker, The New Republic, Harper’s Bazaar, and The Saturday Evening Post. Bulosan’s experiences as a migrant worker deeply influenced his writing, which often depicted the struggles of Filipinos, immigrants, and people of color in the United States.

Bulosan’s literary work was never separate from his commitment to political and social causes. He was a member of the American Writers Association, and he wrote articles and essays advocating for the rights of Filipino and other immigrants. Bulosan was also a member of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), Local 37, and regularly contributed to the local union’s publications.

Because of his work as both a writer and activist, Bulosan was secretly monitored by the US government. Within the context of the Cold War and McCarthyism, authorities deemed Bulosan a threat to the country for his criticism of employers’ treatment of working-class people, as well as US foreign policy in the Philippines.

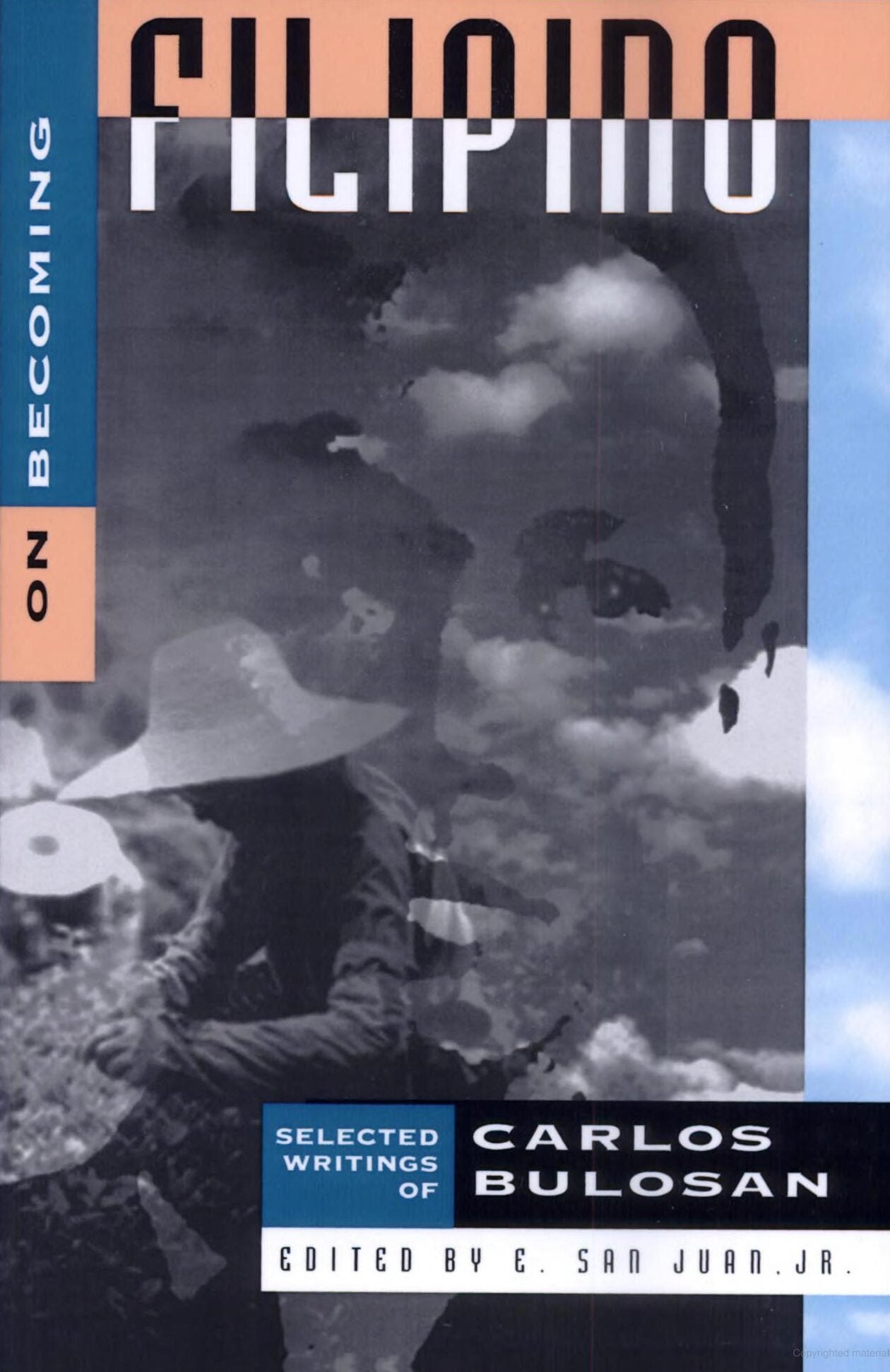

Image 46.04.03 — Pictured is the cover of another book of Carlos Bulosan’s On Becoming Filipino, which compiles many of Bulosan’s writings on his experience as a Filipino in America.

Temple University Press, 1995. Metadata ↗

Portraying the Filipino American Experience in “Freedom from Want”

In his 1943 short essay “Freedom from Want,” Bulosan reflected on the concept of the American Dream and its effects on immigrants in the United States, particularly Filipinos. Bulosan was commissioned to write the essay by the Saturday Evening Post, one of the oldest magazines in the United States. The title refers to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech to rally the nation as it entered World War II. The speech reminded the public that winning the war would guarantee the freedom of speech and worship, and the freedom from want and fear, for people across the world.

Bulosan’s essay emphasized how there are people who are not “free from want” in the United States due to systemic inequities. He challenged idealized views of America by highlighting the struggles of working-class and poor immigrants who made up a significant portion of the population. These are the people who, according to Bulosan, work “upon the forms or upon the hard pavements of the city,” who “clear the forest and mountains of the land,” and “harness wild beast and living steel”— examples of agricultural and industrial labor.

More to explore

Image

“Freedom From Want”

Carlos Bulosan’s essay, “Freedom from Want,” accompanied a Norman Rockwell painting, also titled Freedom From Want, when it was first printed in The Saturday Evening Post in 1943. While both the essay and the painting respond to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech, they present two very different experiences of America. When published side-by-side in print, the differences are heightened.

“Freedom from Want” explores two key themes— exploitation of immigrant labor and the effects of poverty. The essay describes how immigrants are often taken advantage of by employers who pay them very low wages, make them work long hours, and provide them with poor living conditions. “Sometimes we ask if this is the real America,” he says, describing the disillusionment some immigrants felt about the American Dream. Bulosan stressed the contradiction of working to create and harvest the goods and crops that immigrant workers could not afford. “So long as the fruit of our labor is denied us,” he writes, “so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves.” In other words, as long as inequality exists, and some are denied access to a basic living, there would be no such thing as freedom from want.

Bulosan asserts that a just future means one where everyone’s basic needs are met. “When we have enough to eat,” he states, “then we are healthy enough to enjoy what we eat. Then we have the time and ability to read and think and discuss things.” With equal access to resources, people can thrive—not just survive. Bulosan’s essay refers to poverty as a systemic issue, not just a consequence of an individual’s choices. Unfair policies and barriers to access affected more than just families, but entire communities.

While asserting Roosevelt’s goals of freedom across the world, Bulosan reflected the same desire within the United States. Instead of seeing immigrant laborers as outside of the identity of America, Bulosan says, “We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.” Therefore, a person’s inability to make ends meet is due to a systemic failure, not a failure of personal choices.

“Freedom From Want” sheds light on how economic and social systems have historically marginalized working-class and poor immigrants, but Bulosan does not end his essay in despair. According to him, democracy can grow and change through collective action, by “working together— many millions of us working toward a common purpose.”

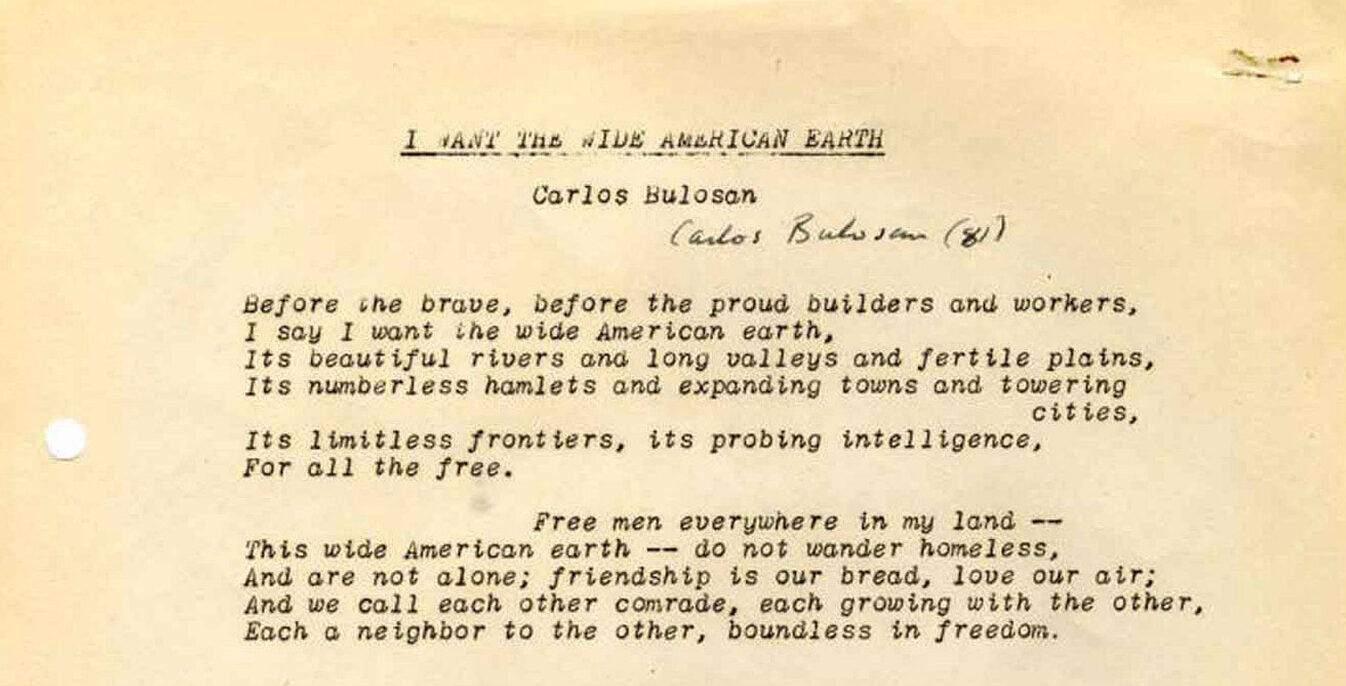

Carlos Bulosan, The Poet

Carlos Bulosan also called for freedom and justice in his poetry. His poem “I Want the Wide American Earth” offers a glimpse into the experiences of Filipino immigrants in America, highlighting the challenges they faced as they navigated exploitation and violence, and the impact that this had on their sense of identity and belonging.

“Their judges lynch us, their police hunt us,” 2 he writes, referring to the violence many Filipinos encountered. Despite this, Bulosan reminds his audience that “we are millions working together” 3 to build the infrastructure of America, and to create life. In other words, his audience outnumbers the people perpetrating violence. To emphasize the power of their numbers, and the importance of resistance, he declares to the judges, police, and others who commit violence against them:

You cannot frighten us with your bombs and deaths;

You cannot drive us away from our land with your hate and disease;

You cannot starve us with your war programs and high prices;

You cannot command us with your nothing,

Because you are nothing but nothing;

You cannot put us all in your padded jails;

You cannot snatch the dawn of life from us!” 4

Bulosan points to the tactics that white supremacists used to intimidate, silence, and kill Filipinos and boldly states that such strategies cannot diminish the people’s will for freedom. Moreover, he refuses the living conditions many immigrant laborers are coerced to accept. “We shall no longer beg you for a share of life,” 5 he proclaims. He affirms that the future is not accepting the subjugation, violence, and erasure of his people, but rather the future is the “wonder of our women” 6 and the “ringing laughter of our children.” 7

Text 46.04.05 — Carlos Bulosan’s signed poem, “I Want the Wide American Earth,” as part of a fundraiser for Local 37 officers’ legal defense fund, who were facing deportation.

Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Metadata ↗

Even though Filipino immigrants encountered setbacks navigating the United States, Bulosan refused succumbing to hopelessness. He reminds his audience that, in their millions, they are not limitless, “unfolding and unfolding, and flowering and flowering / In the bright new sun of our world.” 8 After all, where would the United States be without the “proud builders and workers?” 9

More to explore

Image

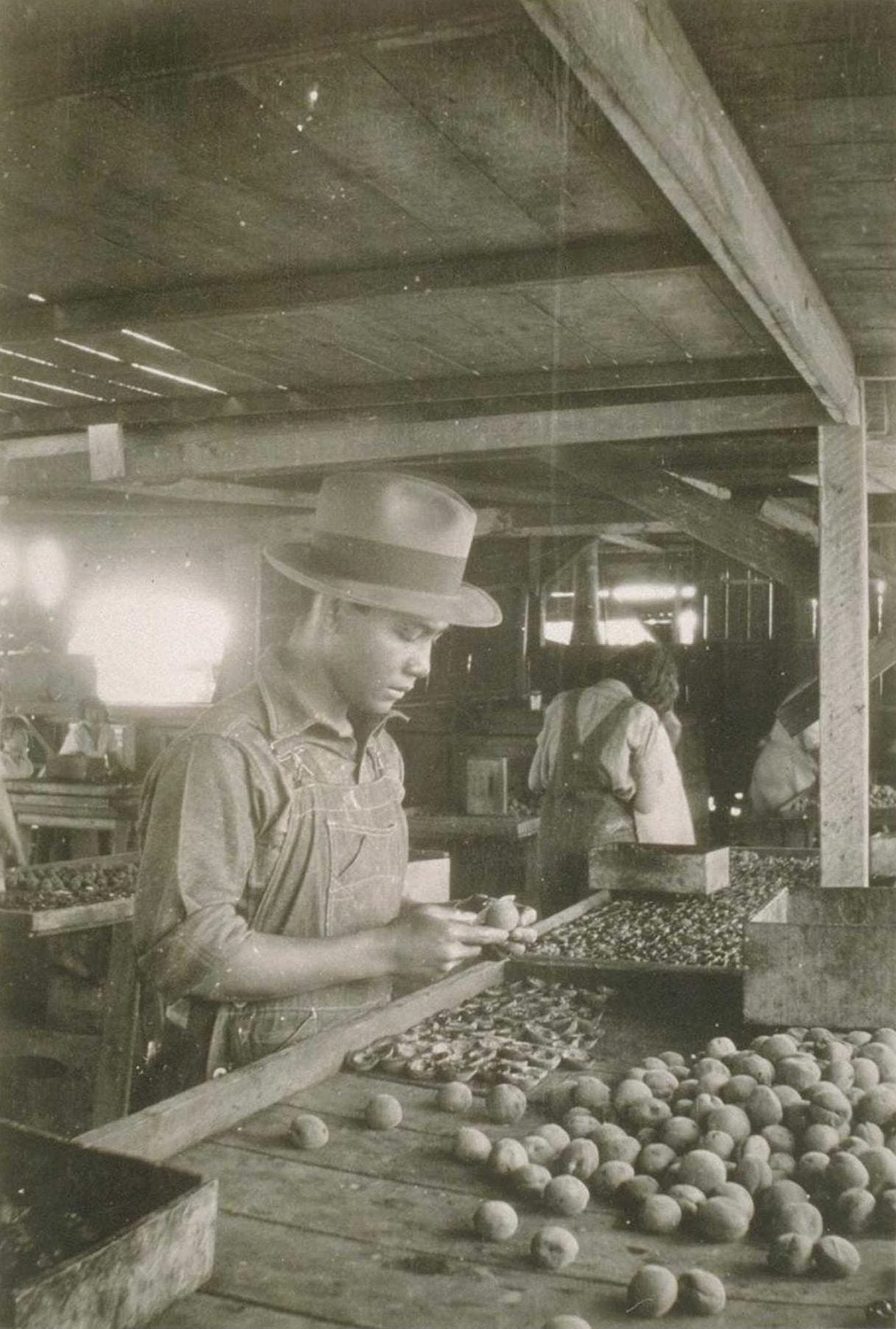

Attitudes towards Filipino Migrants in the Media

A newspaper called The Seattle Times wrote an editorial on its front page that described Filipino migrants as a “problem.” This shows that even in the early twentieth century, many Americans had racist attitudes toward Filipino immigrants.

Overall, “I Want the Wide American Earth” is a powerful and moving work of literature that sheds light on the experiences of Filipino immigrants in America. It serves as a reminder of the importance of resistance, and the need to create a more welcoming and inclusive society for all people.

Fighting Back in America Is in the Heart and Beyond

Carlos Bulosan wrote not only about the discrimination and challenges faced by Filipino immigrants but also how they fought back. Bulosan’s semi-autobiographical novel America Is in the Heart recounts his childhood, experience immigrating to the United States, and the living conditions and struggles of migrant workers at the time.

Bulosan depicted various forms of resistance in his novel, showing how marginalized communities found strength in coming together against discrimination. One way the characters resist oppression is through labor organizing, forming unions, and demanding better wages and working conditions. Another form of resistance portrayed in the novel is education and community building. Characters strive to learn about their rights and culture and gather to support each other. Bulosan writes about learning to read and write in English and also about the rights of man. The novel then shows how education can be a powerful tool for empowerment, as it allows individuals to gain knowledge and understanding of their rights and the broader social and political issues they face.

In addition, America Is in the Heart shows how self-expression through storytelling and the arts can be powerful forms of resistance, as characters share their experiences through writing, music, and other art forms. These acts help to preserve their culture and heritage, challenge stereotypes, and empower the community. Through America Is in the Heart, Bulosan reminds readers that resistance and justice can be found in the most difficult of circumstances.

Bulosan himself was active in labor union organizing, especially in the ILWU Local 37, where he used his skills as a writer to directly support union causes. For example, his poem “I Want the Wide American Earth” benefited the union’s defense fund for its labor leaders Chris Mensalvas and Ernesto Mangaoang, who were arrested and threatened with deportation as part of McCarthy era anti-Communism campaigns in the 1950s. Despite the risks of being targeted like his colleagues, Bulosan raised critiques of US foreign policy in the Philippines in the union’s 1952 Yearbook, a collection of articles, messages, and reports from ILWU members recounting their struggles and accomplishments over the year.

Bulosan’s support for labor unionism, immigrant rights, and human rights in his ancestral homeland were not mainstream ideas during his time. Indeed, these kinds of political orientations were considered threatening and labeled as “Communist” by authorities as a means of undermining activists and organizers like Bulosan. Nevertheless, Bulosan was steadfast in being involved with causes and organizations that supported marginalized communities and often used his writing as a means of amplifying the issues they faced.

Bulosan’s Enduring Legacy

Bulosan passed away in 1956 from surgery complications at the young age of forty-two. According to Bulosan scholar Dr. E. San Juan Jr., Bulosan was censored and isolated as a consequence of his activism, leaving him impoverished at the time of his death. Because of the ongoing struggles of advocating for Ethnic Studies in schools and universities, including Asian American Studies, his legacy is honored by many Filipino American writers and activists today.

Bulosan’s work as a writer and activist has continued to inspire newer generations of Filipino Americans. For example, the Critical Filipina/x/o Studies Collective (CFSC), established in 2003, is a group of scholars who draw from Bulosan’s example by using their writing to support activism in the Filipino community. For two decades, the CFSC has produced reports, statements, and other publications to bring attention to issues facing Filipinos in the Philippines and the broader diaspora around the world. Similarly, the Bulosan Center for Filipinx Studies, established at University of California, Davis, in 2018, produces community-engaged research to amplify issues facing the Filipina/x/o community.

Glossary terms in this module

exploitation Where it’s used

[ eks-ploi-tay-shuhn ]

The dehumanizing treatment and/or unfair compensation of workers.

justice Where it’s used

[ jus-tiss ]

Justice refers to the ideal of fairness and equity in the treatment of all individuals, as well as holding individuals and institutions accountable for their actions. This includes ensuring that everyone has equal rights, opportunities, and protection under the law, and taking steps to rectify past injustices. Justice is a fundamental concept in democratic societies and is central to the protection of human rights and the functioning of a fair and just society.

McCarthyism Where it’s used

[ muh-kar-thee-iz uhm ]

Also known as the Red Scare, McCarthyism is a paranoia about Communism that was part of American society in the 1950s, named after Senator Joe McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin.

migrant worker Where it’s used

[ my-gruhnt wur-ker ]

Someone who moves from place to place, often across national borders, to work temporarily or seasonally.

poverty Where it’s used

[ pov-ur-tee ]

A condition characterized by a lack of access to basic needs such as food, housing, and healthcare that is often caused by systemic inequalities, such as discrimination and lack of access to educational and economic opportunities.

resistance Where it’s used

[ ri-zis-tuhns ]

The actions taken to oppose and challenge oppressive systems and institutions through forms of collective action such as protests, organizing, and activism. It also includes individual acts of rebellion and refusal to comply with discriminatory laws and societal norms. Resistance is a means for marginalized communities to assert their agency and push for equity and justice.

Endnotes

1 Dawn B. Mabalon, Little Manila is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California, (Duke University Press, 2013).

2 Carlos Bulosan, “I Want the Wide American Earth,” Poets.org, accessed September 16, 2024, https://poets.org/poem/i-want-wide-american-earth.

3 Bulosan, “I Want the Wide American Earth.”

4 Bulosan, “I Want the Wide American Earth.”

5 Bulosan, “I Want the Wide American Earth.”

Glossary terms in this module

exploitation Where it’s used

[ eks-ploi-tay-shuhn ]

The dehumanizing treatment and/or unfair compensation of workers.

justice Where it’s used

[ jus-tiss ]

Justice refers to the ideal of fairness and equity in the treatment of all individuals, as well as holding individuals and institutions accountable for their actions. This includes ensuring that everyone has equal rights, opportunities, and protection under the law, and taking steps to rectify past injustices. Justice is a fundamental concept in democratic societies and is central to the protection of human rights and the functioning of a fair and just society.

McCarthyism Where it’s used

[ muh-kar-thee-iz uhm ]

Also known as the Red Scare, McCarthyism is a paranoia about Communism that was part of American society in the 1950s, named after Senator Joe McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin.

migrant worker Where it’s used

[ my-gruhnt wur-ker ]

Someone who moves from place to place, often across national borders, to work temporarily or seasonally.

poverty Where it’s used

[ pov-ur-tee ]

A condition characterized by a lack of access to basic needs such as food, housing, and healthcare that is often caused by systemic inequalities, such as discrimination and lack of access to educational and economic opportunities.

resistance Where it’s used

[ ri-zis-tuhns ]

The actions taken to oppose and challenge oppressive systems and institutions through forms of collective action such as protests, organizing, and activism. It also includes individual acts of rebellion and refusal to comply with discriminatory laws and societal norms. Resistance is a means for marginalized communities to assert their agency and push for equity and justice.

IMAGE

“Freedom From Want“

Image 46.04.04 — A reproduction of The Saturday Evening Post showing Carlos Bulosan’s essay and Norman Rockwell’s painting side-by-side sheds light on the systemic inequities people experience in America.

Saturday Evening Post, 1943. Metadata ↗

Carlos Bulosan’s essay, “Freedom from Want,” accompanied a Norman Rockwell painting, also titled Freedom From Want, when it was first printed in The Saturday Evening Post in 1943. While both the essay and the painting respond to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech, they present two very different experiences of America. When published side-by-side in print, the differences are heightened.

While Rockwell’s painting casts an image of American idealism with an abundance of food, Bulosan’s essay challenges this image with the stark realities of food insecurity for the working class and poor immigrants:

“It is only when we have plenty to eat — plenty of everything — that we begin to understand what freedom means. To us, freedom is not an intangible thing. When we have enough to eat, then we are healthy enough to enjoy what we eat. Then we have the time and ability to read and think and discuss things. Then we are not merely living but also becoming a creative part of life. It is only then that we become a growing part of democracy.”

IMAGE

Attitudes towards Filipino Migrants in the Media

Text 46.04.06 — A newspaper called The Seattle Times wrote an editorial on its front page that described Filipino migrants as a “problem.” This shows that even in the early 20th century, many Americans had racist attitudes toward Filipino immigrants.

University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Metadata ↗

exploitation

[ eks-ploi-tay-shuhn ]

The dehumanizing treatment and/or unfair compensation of workers.

justice

[ jus-tiss ]

Justice refers to the ideal of fairness and equity in the treatment of all individuals, as well as holding individuals and institutions accountable for their actions. This includes ensuring that everyone has equal rights, opportunities, and protection under the law, and taking steps to rectify past injustices. Justice is a fundamental concept in democratic societies and is central to the protection of human rights and the functioning of a fair and just society.

McCarthyism

[ muh-kar-thee-iz uhm ]

Also known as the Red Scare, McCarthyism is a paranoia about Communism that was part of American society in the 1950s, named after Senator Joe McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin.

migrant worker

[ my-gruhnt wur-ker ]

Someone who moves from place to place, often across national borders, to work temporarily or seasonally.

poverty

[ pov-ur-tee ]

A condition characterized by a lack of access to basic needs such as food, housing, and healthcare that is often caused by systemic inequalities, such as discrimination and lack of access to educational and economic opportunities.

resistance

[ ri-zis-tuhns ]

The actions taken to oppose and challenge oppressive systems and institutions through forms of collective action such as protests, organizing, and activism. It also includes individual acts of rebellion and refusal to comply with discriminatory laws and societal norms. Resistance is a means for marginalized communities to assert their agency and push for equity and justice.