Module 5: Philip Vera Cruz

Did Filipino farmworkers achieve justice?

On December 25, 1904, Philip Villamin Vera Cruz was born to Andriano Sanchez Vera Cruz and Maria Villamin Vera Cruz, a hardworking farming family in the town of Saoang, in the province of Ilocos Sur, Philippines. Philip was the eldest of three children, and when his father became very sick when Philip was just a boy, he had to help his family by working in the fields with the other men of the village. Although Philip Vera Cruz dreamed of going to America to study to become a lawyer, his father urged him to remember to support his siblings, both of whom were sixteen years younger than him. He would never forget that promise.

At the age of twenty-one, Philip Vera Cruz departed from Manila, the capital of the Philippines, on April 25, 1926. Accompanied by his uncle Pedro de la Cruz and two friends, they traveled aboard the ship Empress of Asia along with about three hundred other passengers, mostly men. They arrived first after a twenty-two day voyage to Canada in Vancouver, British Columbia, and then continued on by ferry boat to the United States for Seattle, Washington.

Like other Filipino immigrants who discovered the hardships of resettling in the United States, Vera Cruz had to work a variety of seasonal jobs, including at restaurants, country clubs, canneries, and farms in Washington, Alaska, North Dakota, Minnesota, Illinois, and in the Central Valley of California. He attended school while working to pursue his dream of a formal education, while at the same time financially supporting his family back in the Philippines.

By 1942, Vera Cruz was drafted into the US Army. He went to basic training in San Luis Obispo, California, and was assigned to the Second Filipino Infantry Regiment. Discharged due to his age, he was assigned to work the fields of the San Joaquin Valley as part of the war effort. During the 1940s, he worked a nine- to ten-hour day, for 70 to 80 cents an hour. He worked in Delano during the grape season and also picked lettuce and asparagus, thinned plums, and cut raisin grapes throughout the Central Valley. The work in the hot fields was more physically demanding than previous jobs he held in hotels and restaurants.

Who is Philip Vera Cruz?

What was his role in the Farmworkers Movement?

What are lessons from Vera Cruz’s experience in the United Farm Workers (UFW) that can be passed down for future leaders, organizers, and activists towards solidarity and social justice movements?

Agricultural Strikes

Vera Cruz participated in the Stockton Asparagus Strike, his first-ever labor strike, at the age of forty-three. In May 1948, more than four thousand workers (mostly Filipinos) struck with the Cannery Workers Union, part of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) Local 37. The strike was led by trailblazing Filipino labor leaders Chris Mensalvas and Ernesto Mangaoang, the president and business representative of Local 37, respectively. As the strike went on, Vera Cruz and his cousin ran out of money and could no longer pay for their hotel room, so they took a bus to Seattle where workers were often sent to canneries in Alaska. He secured a two-year contract working in Alaska before going back to California.

The Stockton Asparagus Strike had a big influence on Vera Cruz’s beliefs and understanding about labor unions and shaped his future leadership style in the farmworker movement. In addition, having worked in various regions including the Pacific Northwest, the Midwest, and the Central Valley of California, Vera Cruz developed a distinctly internationalist worldview and solidarity with workers globally.

In the late 1950s, Vera Cruz became more involved with unions, including the National Farm Laborers Union (originally the Southern Tenant Farmers Union), which was affiliated with the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO). He served as the president of the Delano local union, which had a membership of several hundred Filipinos, plus some Mexicans and African Americans. This first role as a union leader opened a new chapter in his life in America.

In 1959, the AFL-CIO established the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). Stockton-based farmworker and labor leader Larry Itliong was hired as one of AWOC’s first organizers in Delano. Eventually more Filipino organizers were hired, including Benjamin Gines, Pete Velasco, and Vera Cruz. AWOC’s membership was predominantly Filipino American but also included African Americans, Arabs, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and white people.

On September 7, 1965, the Filipino American members of AWOC came together at the Filipino Community Hall in Delano for a mass meeting and voted to strike. The following day, more than 1,500 Filipino American farmworkers of AWOC refused to work in the grape vineyards of Delano. The strike began during the harvest of the local table grapes throughout the valley. Veteran labor leaders Larry Itliong and Benjamin Gines led AWOC in demanding a wage increase, the right to collectively bargain, and better working conditions in the form of a union contract. Vera Cruz joined his fellow AWOC farmworkers and became a central part of the strike, which turned into a very long five-year struggle against the very powerful agriculture industry of California.

The Filipinos of AWOC anticipated that, in response to the strike, the growers would use divide-and-conquer tactics to split the ethnic groups against each other. And so AWOC leader Larry Itliong reached out to César Chávez, the leader of the Mexican workers of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), in a call for solidarity between the two groups. On September 20, 1965, the Mexicans, led by Chávez and Dolores Huerta, joined the Filipinos, picketing side by side in the fields, and began meeting together at their strike headquarters, the Filipino Community Hall in Delano, to unify their efforts in a shared struggle for justice.

Image 46.05.01 — Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) members picketing in front of Filipino Community Hall as part of the Delano Grape Strike on September 24, 1965.

Courtesy of National Park Service, Harvey Richards Media Archive. Metadata ↗

In August 1966, AWOC and NFWA merged to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC). Chavez served as director and Itliong as assistant director. Vera Cruz was a vice president along with Huerta and two Filipinos, Andy Imutan and Pete Velasco. Although they merged, the groups’ leaders and members held different philosophies, strategies, and organizing styles. Having faced decades of racism, violence, and oppression at the hands of greedy growers, right-wing police, and unjust laws since the 1930s, Filipino strikers tended to have more militant strategies. Chavez exhibited a leadership style that was rooted in the Catholic faith, espousing non-violence that was common during the civil rights movements of the 1960s. The Filipino strikers however tended to advocate for a more self-defense style.

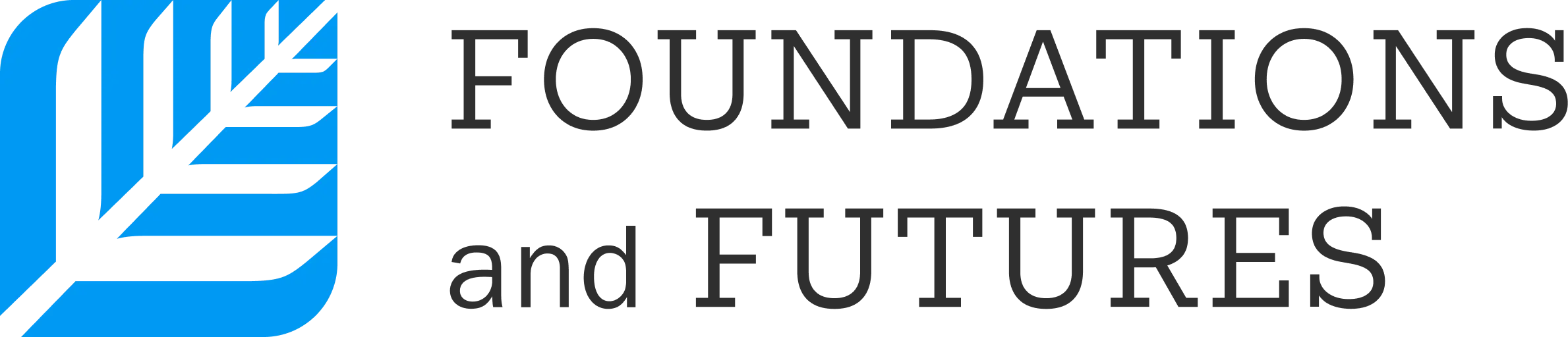

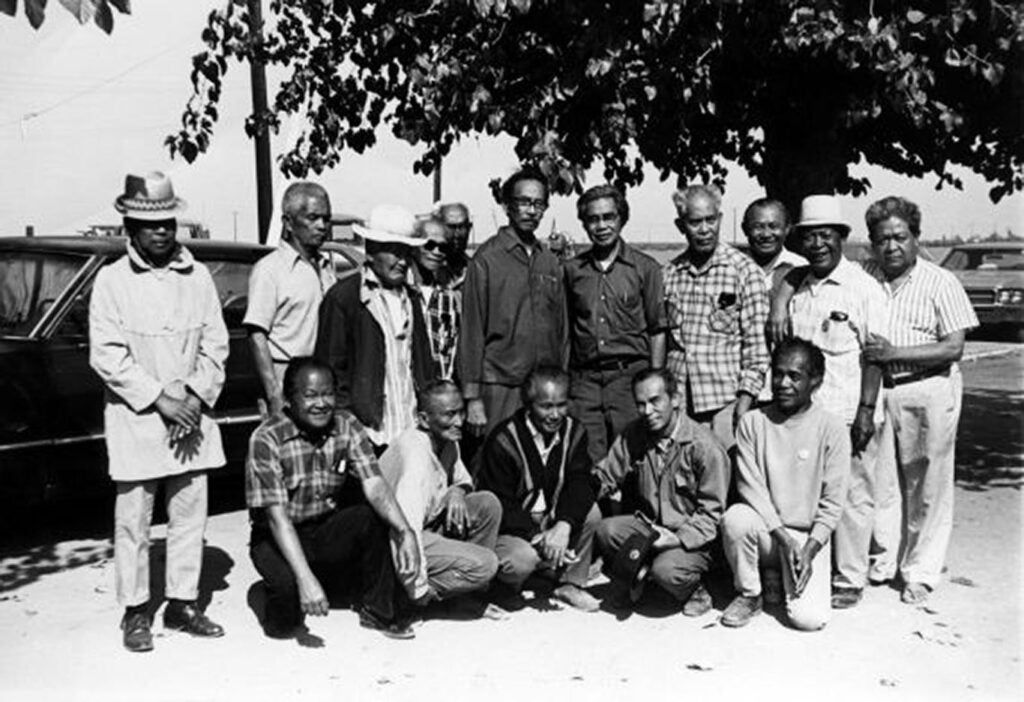

Image 46.05.02 — Philip Vera Cruz (center) and unidentified men at a boycott meeting, circa 1970s.

Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Metadata ↗

The UFWOC initiated an international boycott of table grapes to increase public pressure on the growers. The grape boycott took the fight directly to the people, as union organizers and boycott volunteers traveled far and wide to call on consumers to not buy grapes. In May 1969, Vera Cruz traveled to Europe to build support for the strike and international boycott. He addressed the World Council of Churches Convention on Racism, where convention delegates were moved by his advocacy efforts and adopted a resolution in support of the strike. Finally, after five years, twenty-six Delano-area grape growers signed three-year contracts with the UFWOC at their headquarters, “The Forty Acres,” on July 29, 1970. In 2008, The Forty Acres was named a National Historic Landmark because of the grape strike’s significance in the labor movement.

The new contracts signed with the growers increased workers’ wages from $1.10 to $1.80 an hour, plus 20 cents for each box picked, and secured union representation for ten thousand farmworkers. The contract also required growers to contribute to the union health plan. The UFWOC continued to organize and ultimately unionized about seventy thousand farmworkers and brought the entire California table grape industry under contract. Subsequently, on February 19, 1972, the UFWOC became the United Farm Workers (UFW), and was accepted into the AFL-CIO. By 1975, the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act was enacted, officially establishing the right to collective bargaining for farmworkers, a first in US history.

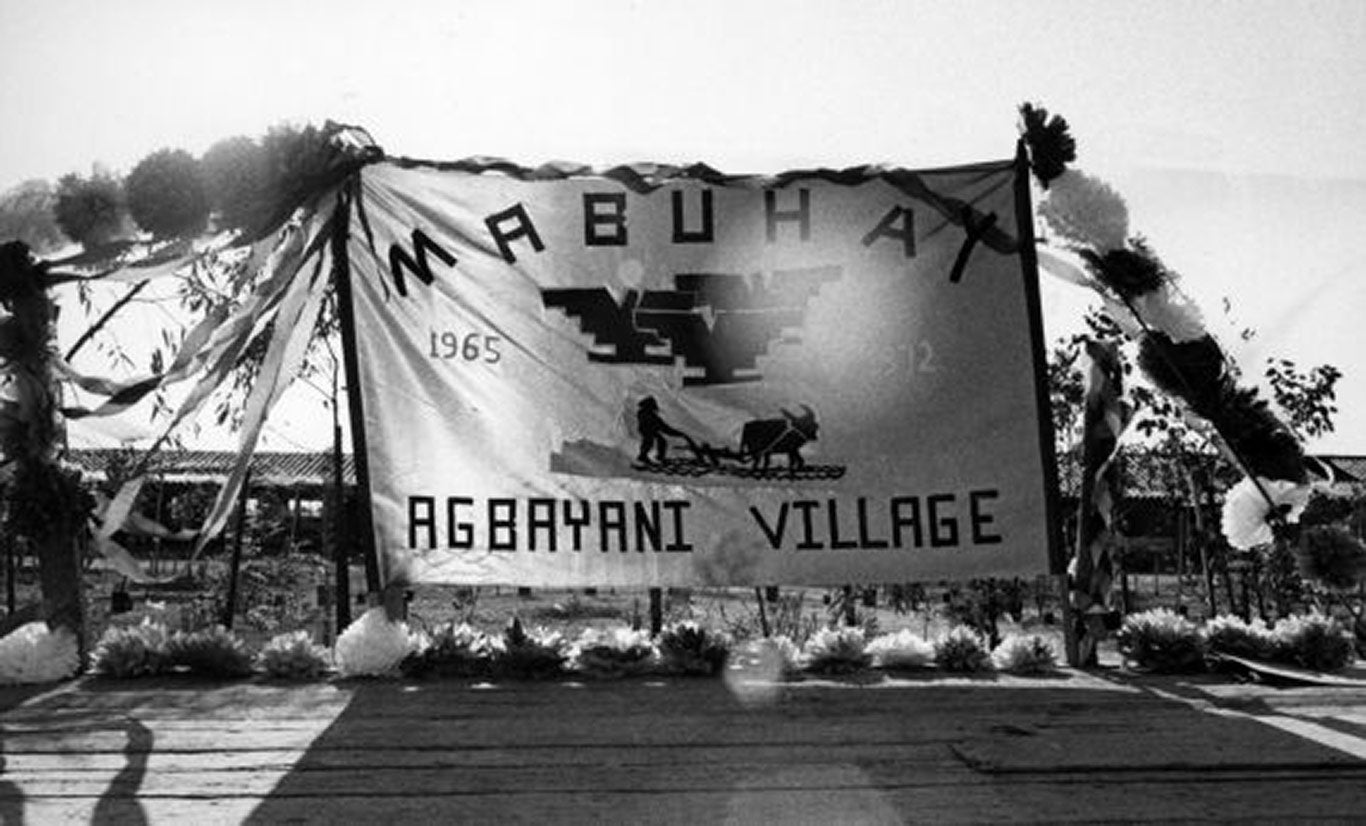

Paulo Agbayani Retirement Village

In 1971, Philip Vera Cruz served as project director for the Paulo Agbayani Retirement Village. The village is one of four buildings at The Forty Acres, the original headquarters of the UFW in Delano, California. Construction of the village began in 1973 with hundreds of volunteers and laborers from across the nation and around the world. Following its completion, the village was dedicated on June 21, 1974. Most of the Filipino farmworkers who had migrated to the United States in the 1920s and 1930s were of retirement age and needed affordable housing in the 1970s, and the village provided these elders who did not have family, or a place to stay, with their own community. Today, Agbayani Village is one lasting marker in the US that commemorates Filipino farmworkers.

Disillusionment in the Union

As time went on, differences in styles and strategies within the United Farm Workers led to dissatisfaction and disillusionment among the Filipino rank-and-file members. Filipinos, who had built up seniority in AWOC, felt the new hiring hall system of the UFW was unfair. Many Filipino farmworkers were seasonal laborers accustomed to being hired by the growers’ labor contractors for decades, while the hiring hall matched jobs to union members, with special consideration for local farmworkers who resided near the farms over seasonal laborers. Outnumbered and aging, many Filipino members felt squeezed out of the union. Nearly all the veteran Filipino organizers began to leave the union. For years, only Vera Cruz and Pete Velasco, remained in the leadership of the UFW.

As a vice president of the union, Vera Cruz advocated for the needs of the aging Filipino farmworkers as disappointment and disillusionment continued to grow among the manongs. The final straw for Vera Cruz was when César Chávez traveled to the Philippines in 1972 to receive an award from the country’s president, Ferdinand Marcos. Because Marcos was a dictator who declared agbayani-village martial law and whose government was brutally violent and oppressive to Filipino people, Vera Cruz opposed Chávez’s visit, stating that it contradicted union values. Vera Cruz resigned from the UFW Board soon after.

Activism Beyond the Union

Upon leaving the union, Philip Vera Cruz lived with his longtime companion and partner Debbie Vollmer in Bakersfield and remained active in various union and social justice causes, including the Anti–Martial Law, the antiwar, the Filipino American political empowerment, and the Asian Pacific American civil rights movements. Vera Cruz was an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War and spoke at an antiwar rally at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco on April 24, 1971, attended by 156,000 people. That rally was the largest of its kind to date on the West Coast. Like writer and activist Carlos Bulosan, Vera Cruz also wrote poetry as a form of labor and political activism.

His poem “Profits Enslave the World” inspired musician and songwriter Chris Bautistia to write a song of the same name featuring Vera Cruz’s poetry in the lyrics. The song became an anthem of the social justice movements of the 1970s and 1980s. Vera Cruz was also an active leader of the Filipino American Political Association (FAPA), a national organization with several chapters across the country. He served as president of the Delano chapter and hosted the first national FAPA convention at the Filipino Community Hall in April 1969.

We can see during this era that decades of labor organizing by farmworkers had evolved into growing political activism and coalition building. These new organizations would serve as a foundation for future Filipino American community advocacy groups on a national scale.

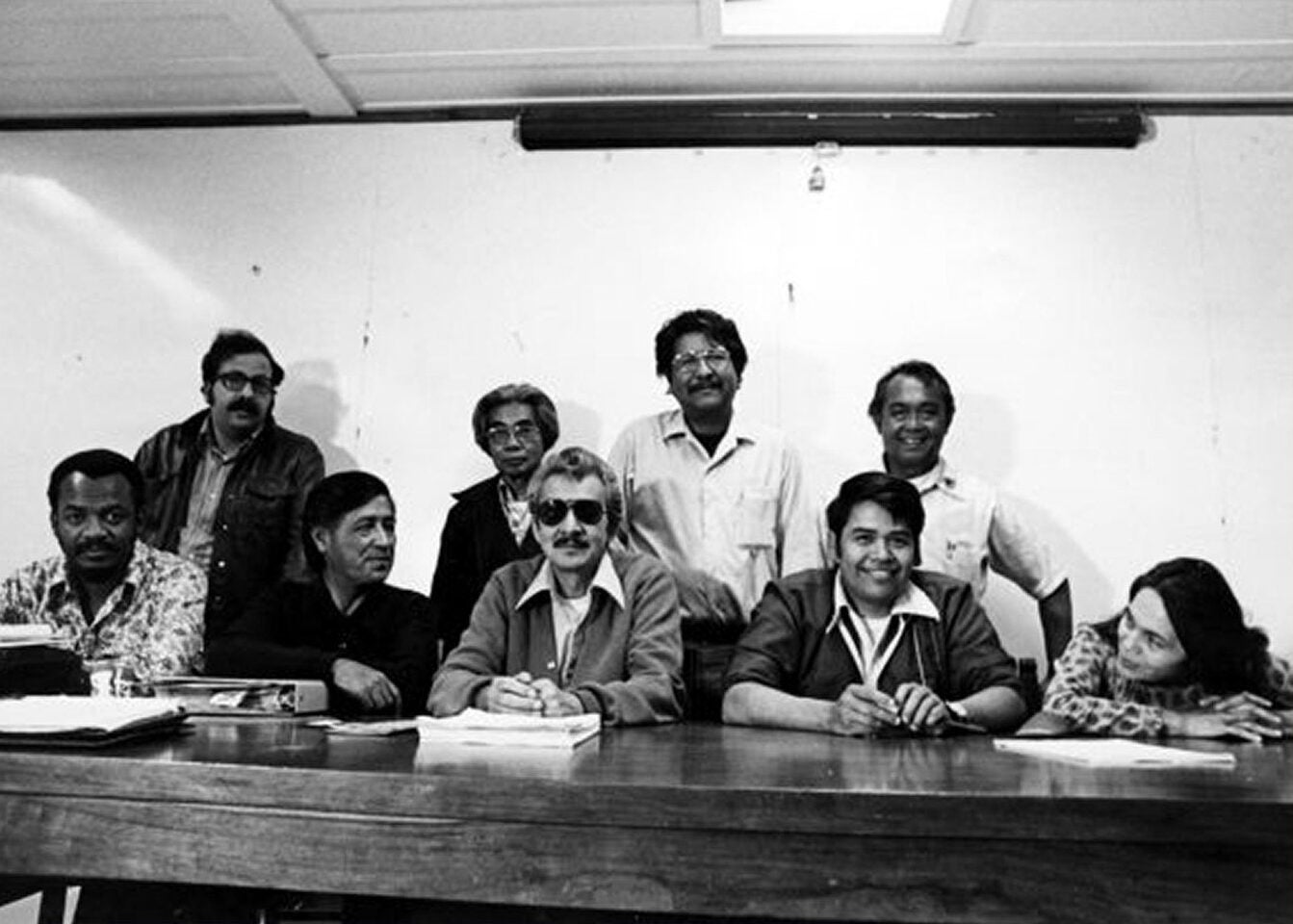

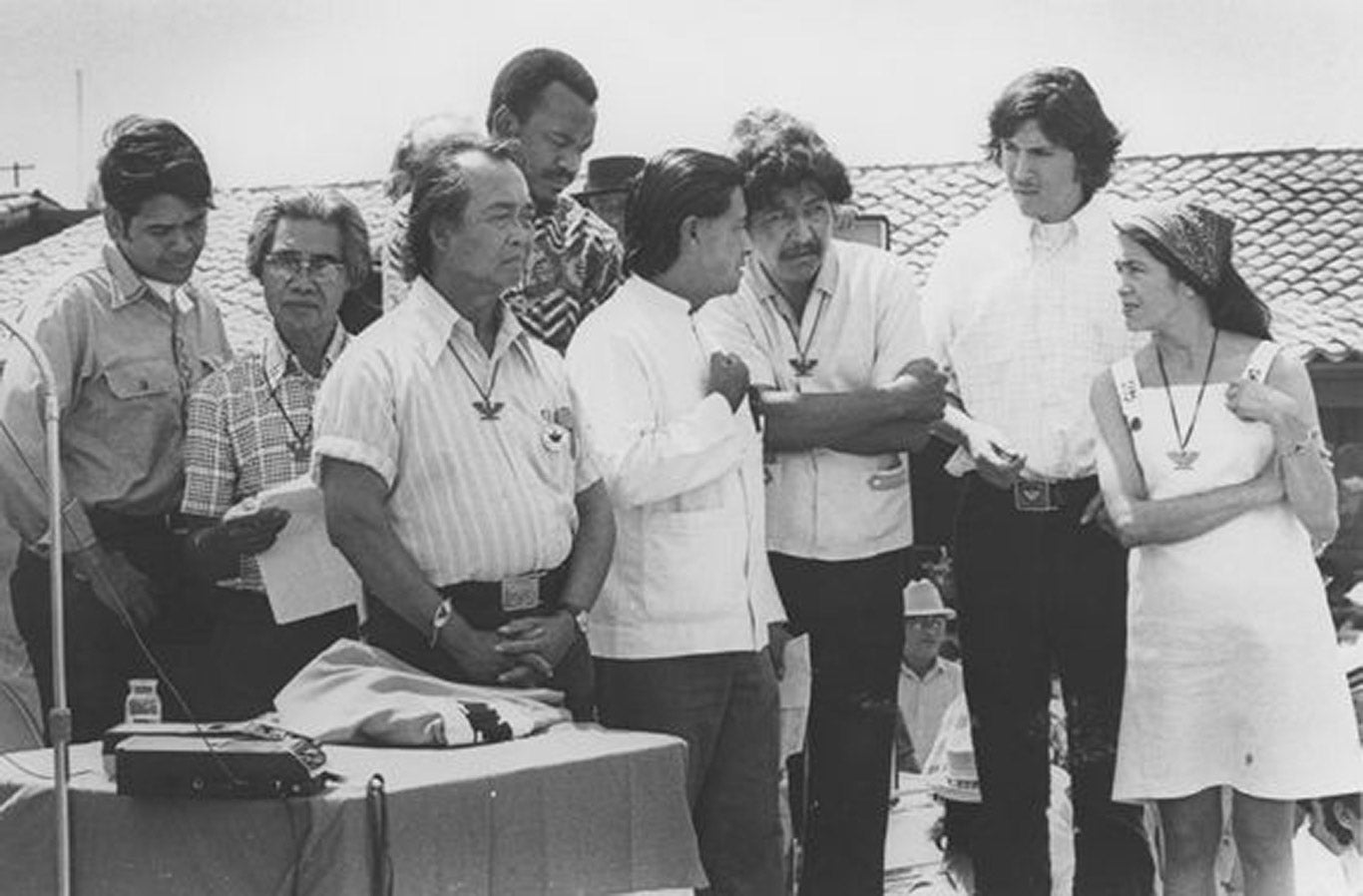

Image 46.05.04 — Paul Schrade of the Delano chapter speaks at the Filipino American Political Association (FAPA) Convention in April, 1969.

Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Metadata ↗

His Legacy Lives On

Philip Vera Cruz received numerous honors for his role in Filipino American history and the farmworker movement. In 1987, Vera Cruz was awarded the first Ninoy M. Aquino Award for lifetime service to Filipino Americans in the United States, at the age of eighty-two. The next year, he and his partner Debbie Vollmer traveled to the Philippines to meet with President Corazon Aquino at Malacanang Palace, which was the first time he had been back to the country since leaving many decades before. In 1992, the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA), AFL-CIO honored Vera Cruz as an “Asian Pacific American Labor Pioneer” for his leadership and service. On June 20, 1993, Vera Cruz delivered the community keynote commencement speech at the first annual UCLA Pilipino Graduation Ceremony at Kerckhoff Hall Plaza.

Vera Cruz died on June 10, 1994, at the age of eighty-nine, at Mercy Hospital in Bakersfield, California, due to emphysema and complications from lung surgery. The same year, APALA established the annual Philip Vera Cruz Award, recognizing outstanding Asian American Pacific Islander union organizers whose efforts exemplified his legacy. In 1995, Vera Cruz was prominently featured, along with Larry Itliong, in a mural in Los Angeles’ Historic Filipinotown district, painted by artist Eliseo Art Silva. In 2013, the school board in Union City, California, renamed Alvarado Middle School to Itliong–Vera Cruz Middle School, in honor of the two pioneering leaders. In 2014, a freeway overpass in San Diego, California, was designated as the Itliong–Vera Cruz Memorial Bridge.

Philip Vera Cruz’s life of work, organizing, and activism truly exemplifies the need to continuously struggle and fight for workers’ rights, social and economic justice, and progressive change in American society.

Author’s note: This narrative includes excerpts from “Philip Vera Cruz” by Mark Pullido in the Sage Encyclopedia of Filipina/x/o American Studies.

Glossary terms in this module

Agbayani Village Where it’s used

Agbayani Village was a housing facility built in 1974 for the elderly farm workers who could no longer work or wished to retire. Students and activists from across California came to help raise money and build the facility for Filipino and Chicano elders. Agbayani Village is named after Paulo Agbayani, one of the Filipino farm worker elders who participated early in the Delano Grape Strike but died of a heart attack while picketing on the front lines.

collective bargaining Where it’s used

The negotiation of wages, working conditions, and treatment of workers that is organized by a body of employees.

labor organizing Where it’s used

When workers join together to fight for better conditions, pay, and benefits at their job, usually by creating a union.

martial law Where it’s used

A form of government that consolidates state and military forces to ban political protest, suppress independent media, and unilaterally target anyone suspected of opposing ruling forces. In the Philippines, dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972. The Philippines remained under martial law for fourteen years until Marcos was ousted following the People Power Revolution in February 1986.

strike Where it’s used

A deliberate plan to stop working as a collective form of protest against an unjust employer or employment practices and/or conditions.

unions Where it’s used

An organization formed by workers, typically from the same industry or company, for the purpose of maintaining and improving the conditions of their workplace.