Module 2: Setting the Stage for Japanese American Mass Incarceration

How can an entire racial group be unjustly incarcerated in a democracy?

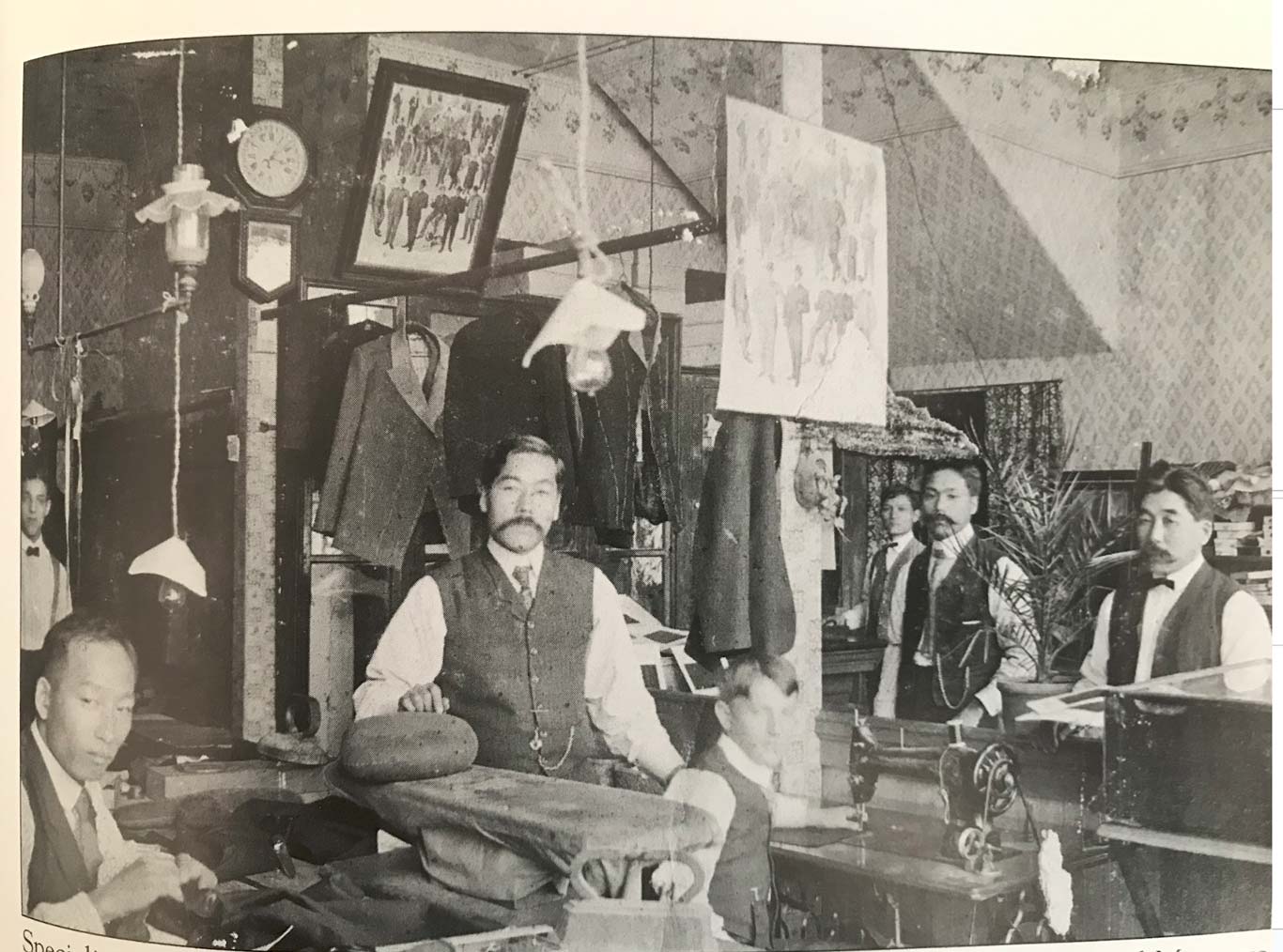

In this module, you will meet the Yasui family of Hood River, Oregon, and learn how Japanese immigrants in the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries experienced racism and discrimination. You will also learn about the development of thriving Japanese American communities and successful businesses before the Empire of Japan attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaiʻi.

Why did people from Japan immigrate to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and how did they develop communities in the US?

How were Japanese immigrants and their children treated in the United States, locally and nationally?

What factors contributed to the decision to force Japanese Americans from their homes and incarcerate them?

Go East, Young Man!

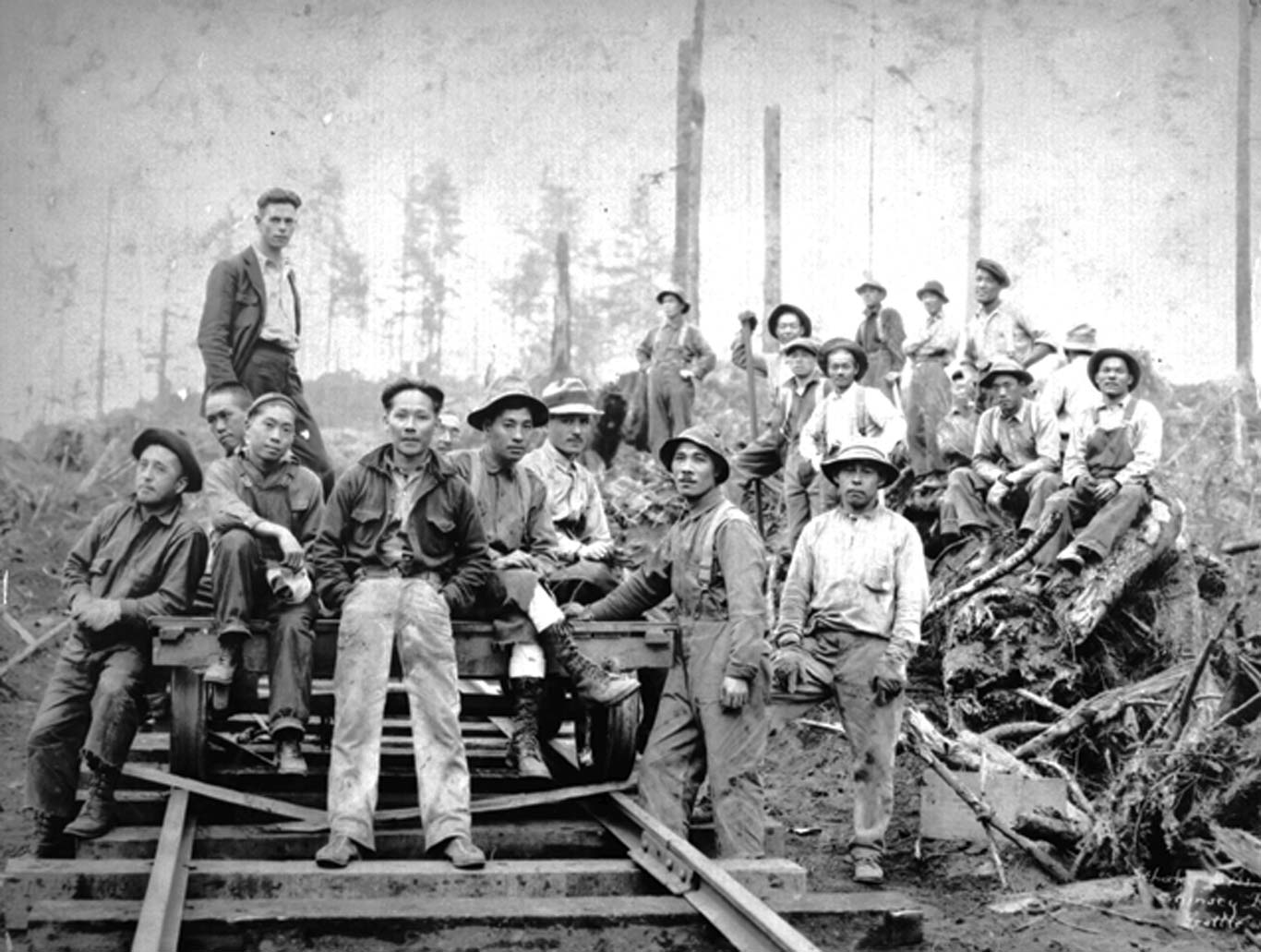

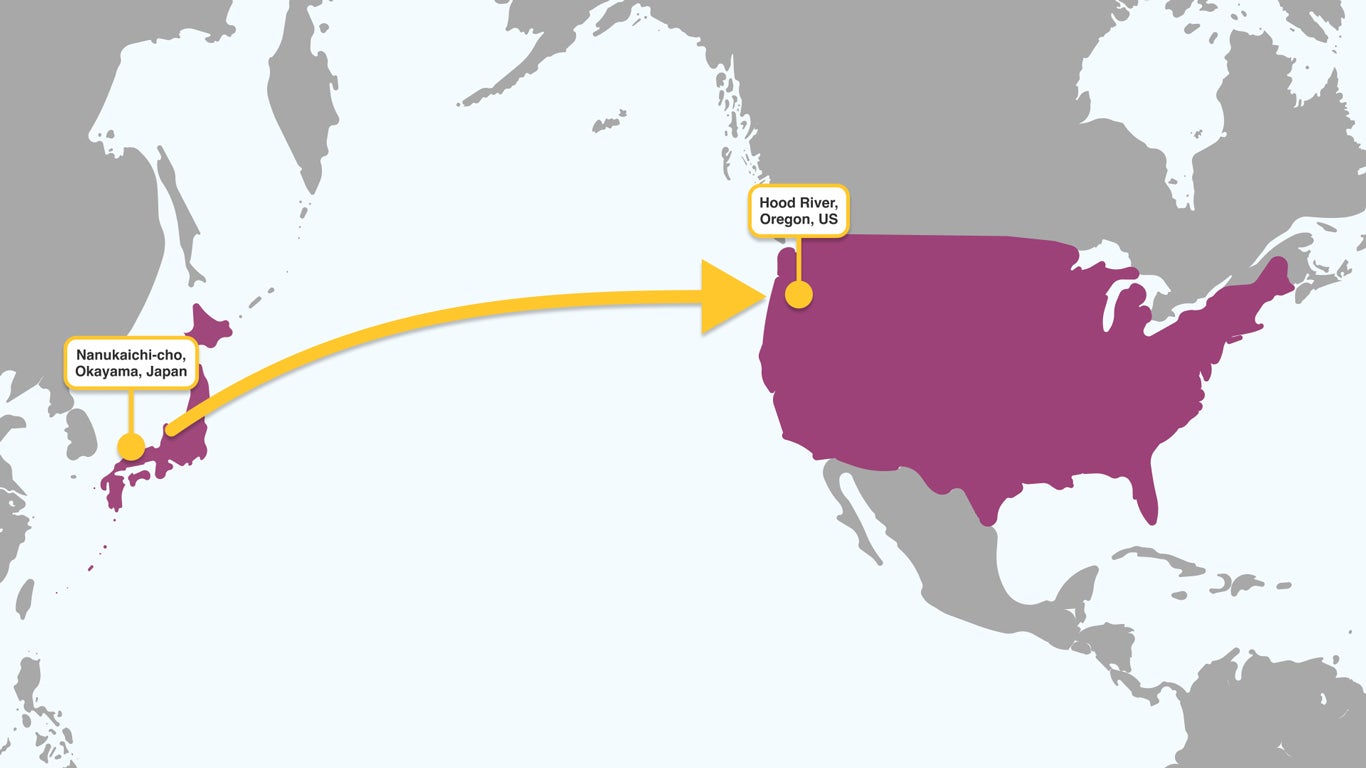

Masuo Yasui was sixteen years old in 1903 when he packed a wicker trunk and left his small village in southwestern Japan to sail across the Pacific Ocean. He made the long journey to join his father and two older brothers, who were laying railroad ties and tracks in the western United States.

As the youngest child in his family, Masuo knew that his future in Japan was not promising. Following Japanese custom, his eldest brother would inherit the family’s small farm, while Masuo would get nothing. Even if he were to inherit any land, the Japanese government had been heavily taxing farmers like his father to pay for modernizing the country. When Masuo was a child, his father left for the United States, where he could earn more money.

When Masuo reached the age he could work, his father ordered his son to join him in the United States. The lure of a new country tugged at Masuo. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, tales of America’s wealth and opportunities spread throughout Japan. In cities, a new form of entertainment called moving pictures awed Japanese audiences with romanticized images of the American West. Teachers encouraged young men like Masuo, who would not inherit any family wealth, to go to the US. Thousands of adventurous young men did.

When Masuo arrived in the United States in 1903, he found that his five-foot, two-inch, 120-pound frame did not lend itself to the grueling physical labor of building the railroad. He ended up as a cook, serving meals to the men constructing the railroad.

Masuo’s father and eldest brother, having saved some money, later returned to Japan. But Masuo stayed in the United States with another older brother. After working briefly in a salmon cannery on the northwestern tip of Oregon, Masuo moved to Portland, where he studied English and converted to Christianity.

The Yasui brothers eventually settled in the fertile Hood River Valley, about sixty-five miles east of Portland, where they opened a store on a hill overlooking the Columbia River in the small town of Hood River.

Unwelcome Immigrants

Japanese immigrants, or Issei, filled a labor vacuum that Chinese immigrants previously occupied. Anti-Chinese racism resulted in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred virtually all immigration from China. Agricultural businesses and the owners of railroads and mines still needed workers, however, and they looked to Japan for laborers.

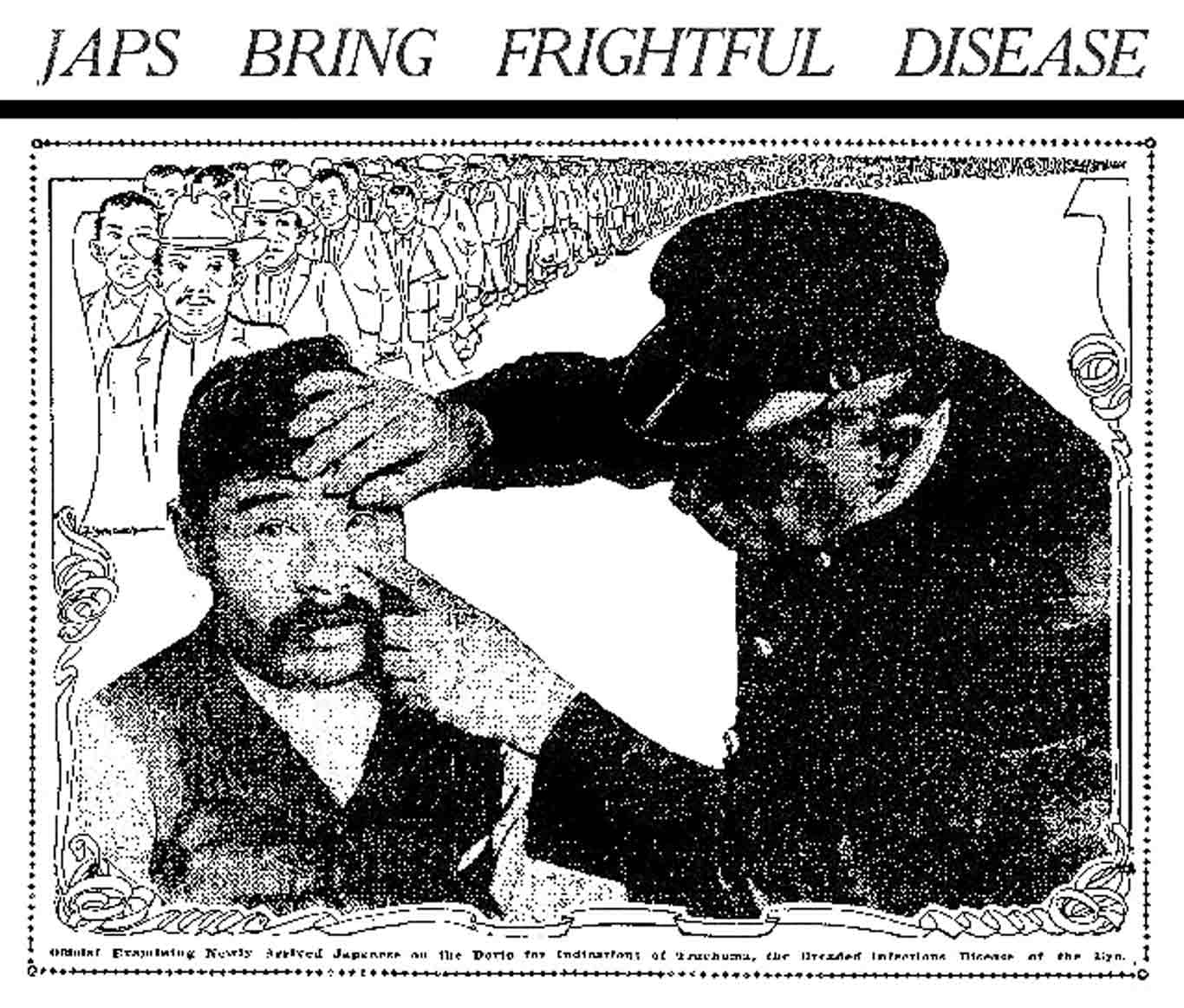

Many Americans, especially on the West Coast, viewed Issei similarly to the Chinese immigrants before them—as immoral, degenerate, and unassimilable. White laborers resented economic competition from Issei workers. Labor groups, agricultural organizations, nativists, and politicians organized an anti-Japanese campaign to end immigration from Japan, stoking unfounded fears that the United States would be invaded by unwanted and dangerous Asian “hordes” that threatened the white race.

In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated with Japan on what became known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement, under which the Japanese government voluntarily regulated immigration to the United States, effectively ending the immigration of laborers. The agreement, however, allowed Issei men already in the US to bring their families to live with them. Consequently, thousands of Japanese women immigrated to the United States until a total ban on Japanese immigration was enacted in 1924.

Building Communities

In 1910, when he was twenty-three, Masuo began corresponding with Shidzuyo Miyake, a young woman he knew from his village in Japan. By then, Shidzuyo was working as a teacher at a girls’ school on a tiny island in the Inland Sea of Japan. She had studied beyond the six years of compulsory education and was earning her own money, which was unusual for Japanese women of her generation.

Image 45.02.03 — Shidzuyo Yasui and six of her children in 1924. Because Japanese women could legally immigrate, unlike most Chinese women, Issei could form families. Their children became citizens by birth and rooted Issei in the United States, where they built communities along the West Coast.

Courtesy of Densho, Yasui Family Collection. Metadata ↗

Masuo proposed to Shidzuyo via letter, and she accepted. In 1912 she crossed the Pacific and joined him in Hood River. They had nine children between 1913 and 1927.

The Yasui brothers’ store was successful, and Masuo expanded into other business ventures: contracting Issei laborers, buying more than three hundred acres of undeveloped land, and selling parcels to fellow immigrants. By 1920, Masuo owned or co-owned five orchards in the area, and he had helped dozens of Issei purchase or lease land. He pioneered asparagus as a crop in Hood River, and he and other Issei became the leading producers of asparagus and strawberries in the region. Masuo was honored within the Japanese American community for his leadership, and the wider white population also recognized his contributions, though sometimes begrudgingly. He became the first non-white member of the local Rotary Club and the first Japanese person to be elected to the Hood River Apple Growers Association board of directors.

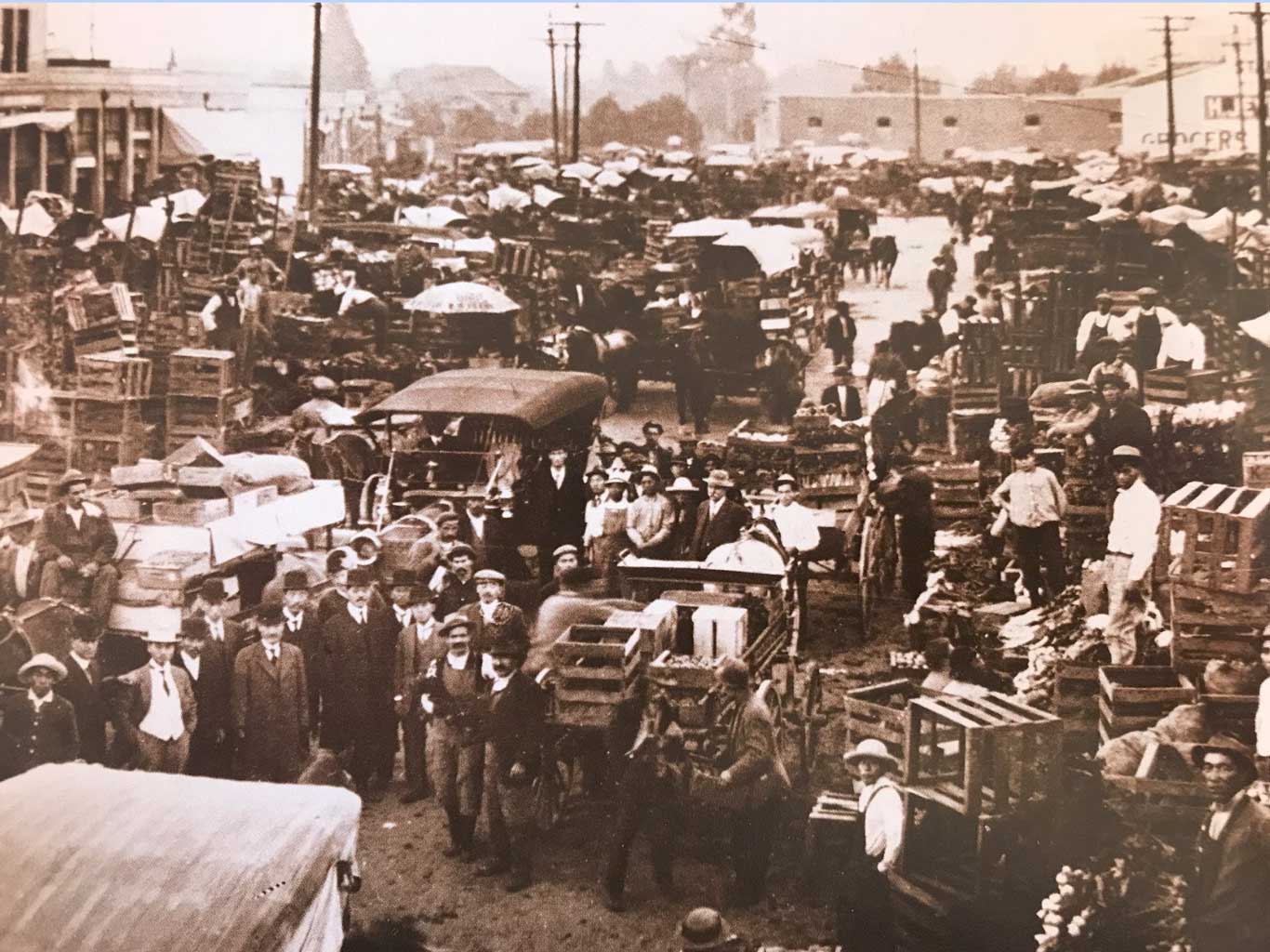

Japanese American farmers throughout the West Coast were successful in growing fruits, vegetables, and flowers. They also established fishing communities in California coastal cities like Terminal Island (part of San Pedro), San Diego, and Monterey. The Issei’s achievements bred resentment and jealousy from competing farmers and fishermen who organized to seize control of their economic sectors.

Fear and Anger: Discrimination Against Japanese Americans

Many white farmers who resented Japanese Americans’ success and feared competition organized to drive them out. White growers in Hood River, Oregon, for example, formed an Anti-Asiatic Association, which sowed fears that Issei were taking over the region despite their small numbers and lobbied for a law forbidding Issei from buying land, which the state passed in 1923. Luckily, Masuo and other Japanese immigrants in Hood River who bought land before the Oregon law took effect were able to continue living and working there.

California and Washington also passed Alien Land Laws, as did twelve other states—including Florida, Minnesota, and Texas, which had miniscule or no Japanese American populations. These laws did not explicitly state that Japanese immigrants couldn’t own land. Instead, they barred “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from purchasing and leasing land.

In the early twentieth century, citizenship was restricted to “free white persons,” people of African descent, and anyone born on US soil. The 1922 Supreme Court ruling in the case Takao Ozawa v. United States confirmed that Japanese and other Asian immigrants could not become naturalized citizens.

Anti-Japanese exclusionists were not satisfied with preventing Issei from gaining citizenship, and they succeeded in convincing Congress to ban Japanese immigration. The Immigration Act of 1924 barred immigration from Japan and other Asian countries, except the Philippines, which was then a US colony.

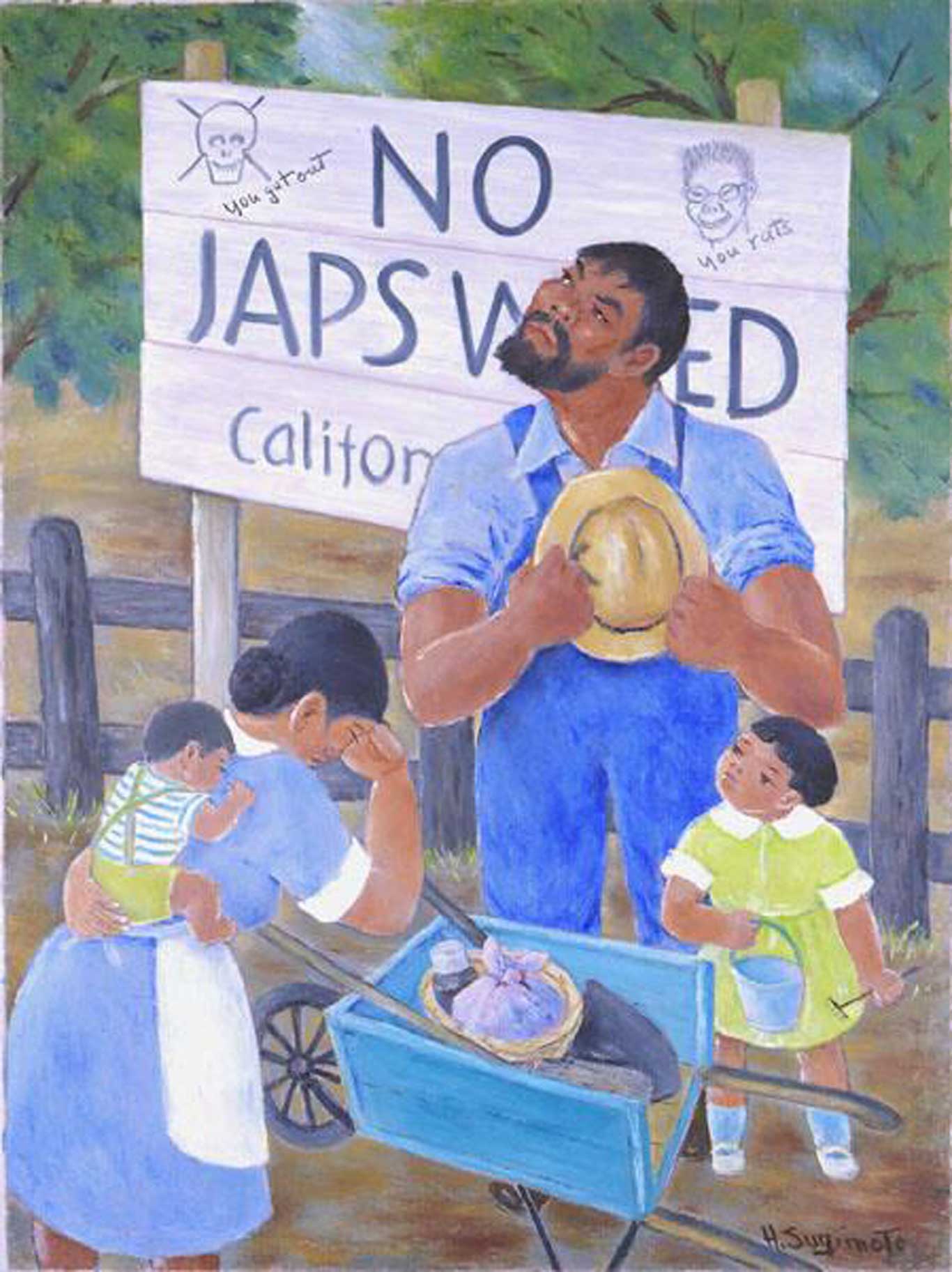

Issei and their children, the Nisei (a term that refers to the second generation), not only had to contend with federal and state laws restricting their rights. They also faced daily slights and discrimination. For example, a white friend of the eldest Yasui son, Kay, never invited the young Nisei into his home. The reason: The friend’s mother feared Kay Yasui because of his race. And when the Yasui children went to see movies at the Rialto Theater in Hood River, they were not allowed to sit on the main floor. They had to sit in the segregated balcony.

Japanese Americans along the West Coast faced similar discrimination: Restaurants denied them service, barbers refused to cut their hair, and landlords would not rent to them.

Image 45.02.05 — This painting by Henry Sugimoto depicts a Japanese American family forced to leave their rural community.

Courtesy of Japanese American National Museum. Metadata ↗

Vibrant Communities

Despite growing anti-Japanese discrimination, vibrant Japanese American communities thrived along the West Coast. Masuo and Shidzuyo Yasui led a successful effort in 1926 to build the Hood River Japanese Community Hall on property that the Yasui family owned.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Issei entrepreneurs established successful businesses and religious leaders formed temples and churches. Issei and Nisei organized cultural, social, professional, and political groups. All-Japanese athletic teams, literary societies, and theatrical groups flourished in Japantowns on the West Coast. The Yasui boys played baseball and basketball in the Hood River area’s Nisei Athletic Club.

More to explore

It All Came Crashing Down

The lives of Japanese Americans changed forever on December 7, 1941, when the Empire of Japan bombed the United States military base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaiʻi. Japan’s rapid military and colonial expansion in Asia during the early twentieth century fueled fears of a Japanese invasion in the United States. Similarly, racist demagogues had, for decades, stoked fears that Japanese immigrants and their children would take over white communities. Organizations and individuals, who had been sharing these racist beliefs for years, harnessed other Americans’ fear and anger about the bombing of Pearl Harbor. They pushed the government to force Japanese Americans from the Pacific coast states.

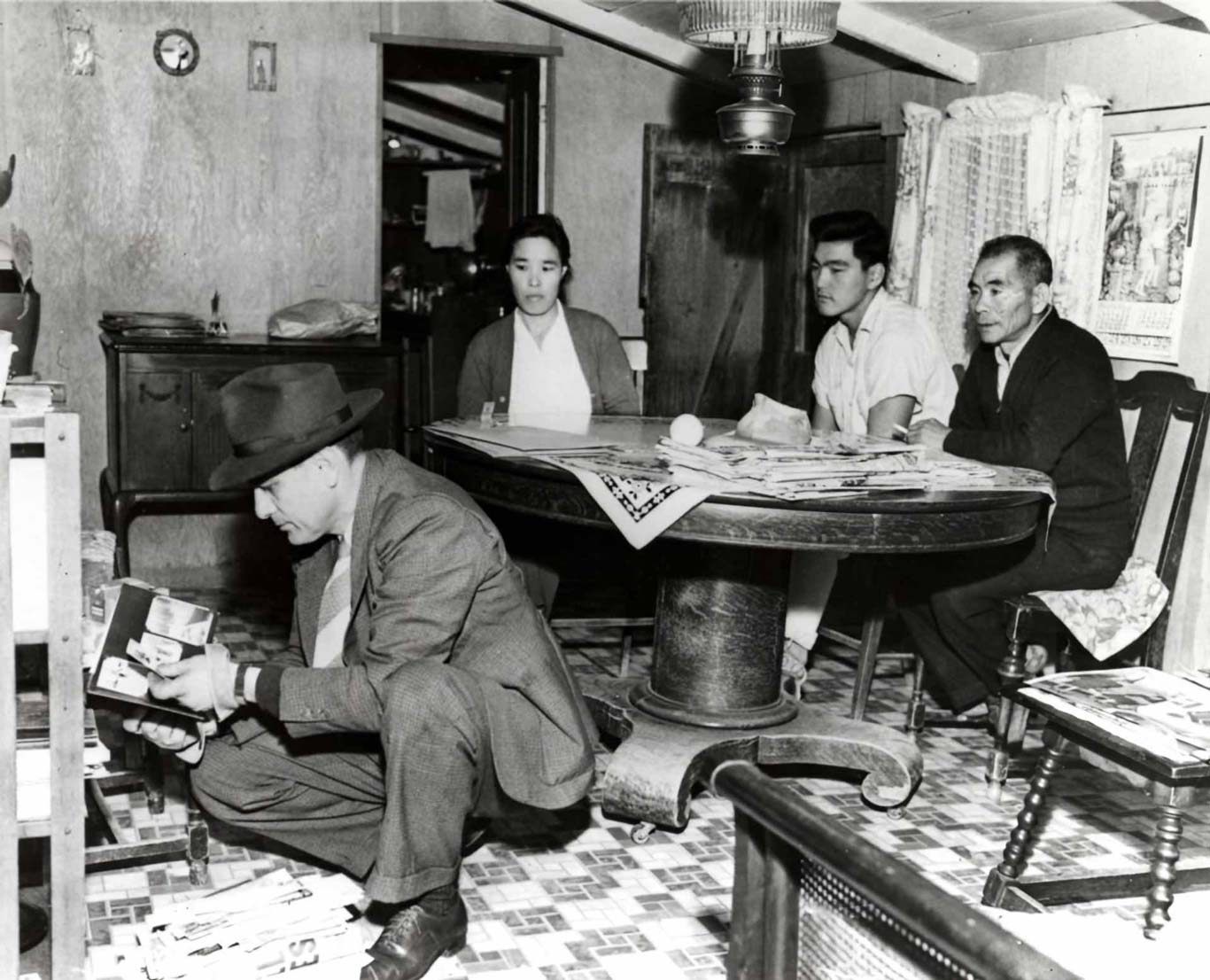

The government froze all Issei bank accounts and started arresting leaders of Japanese American community organizations. In Hood River, federal agents boarded up the Yasui store. The Yasui family’s home was one of the first that FBI agents searched in the days following the Pearl Harbor attack. Agents confiscated a scroll with Japanese writing certifying Masuo’s judo training, as well as maps that some of the Yasui children had drawn as a school assignment. Similar searches took place in Japanese American homes all along the West Coast in the days immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Agents took cameras, weapons, and any evidence of a connection with Japan.

The FBI targeted people based on pre-existing lists the agency had created of Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants who were leaders in their communities or whom the government suspected of being dangerous. In the hours and days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, FBI agents arrested, without charges, many of the men on those lists. Among them was Masuo Yasui, whose leadership in the Hood River community made him especially vulnerable.

Masuo was not the only member of the family to face hardship. The government instituted an 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew on German and Italian immigrants and all people of Japanese ancestry, even American citizens like the Nisei in the Yasui family. The same groups were not allowed to travel five miles beyond their homes at any time of day or night. These restrictions further isolated the Yasuis and other Japanese American families.

More to explore

Video

04:58

Homer Yasui recalls Pearl Harbor

In this video, Homer Yasui recalls December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese military attacked the US military base at Pearl Harbor, and describes where each of his family members were at the time.

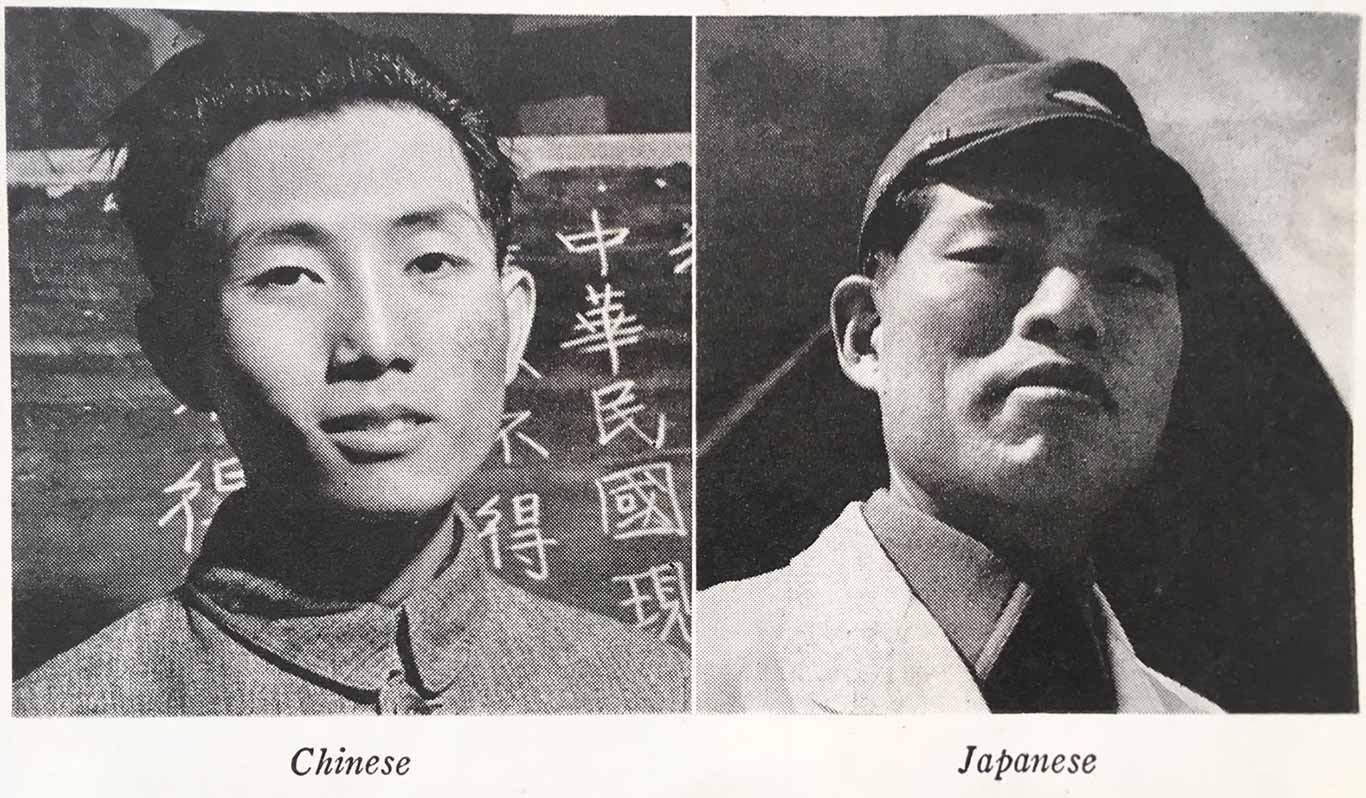

Wild rumors spread throughout the West Coast that Japanese Americans in Hawaiʻi had cut sugarcane fields in the shape of arrows pointing to Pearl Harbor and blocked roads with their produce trucks to hinder rescue efforts. The secretary of the Navy claimed, without any evidence, that the Japanese in Hawaiʻi had engaged in sabotage.

Anti-Japanese racists saw their opportunity to rid the West Coast of the Japanese. An official of a California agricultural organization openly spoke of the economic motivations behind some of their actions: “We’re charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We might as well be honest. We do. It’s a question of whether the white man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown man. They came [here] to work, and they stayed to take over.” 1

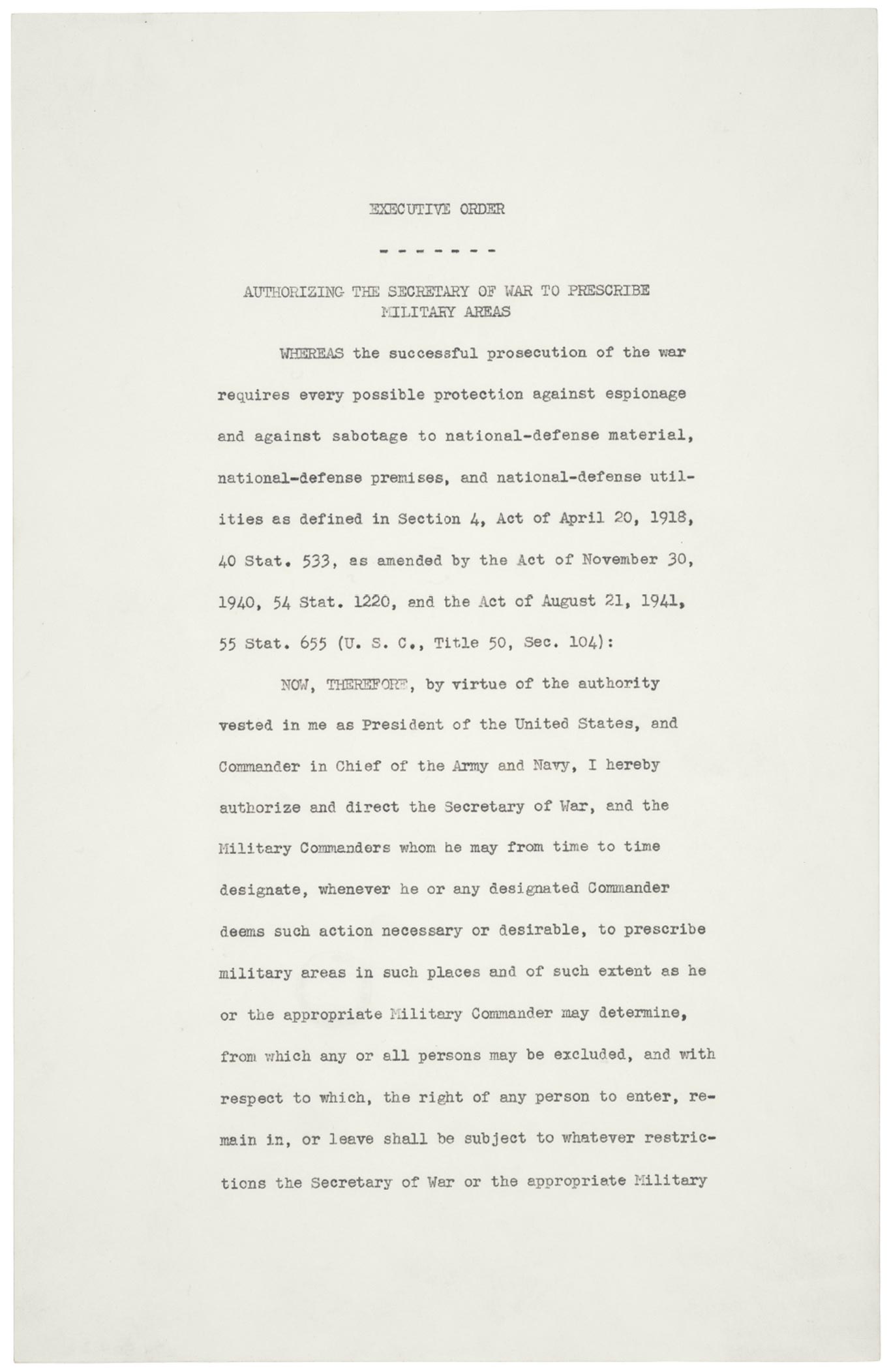

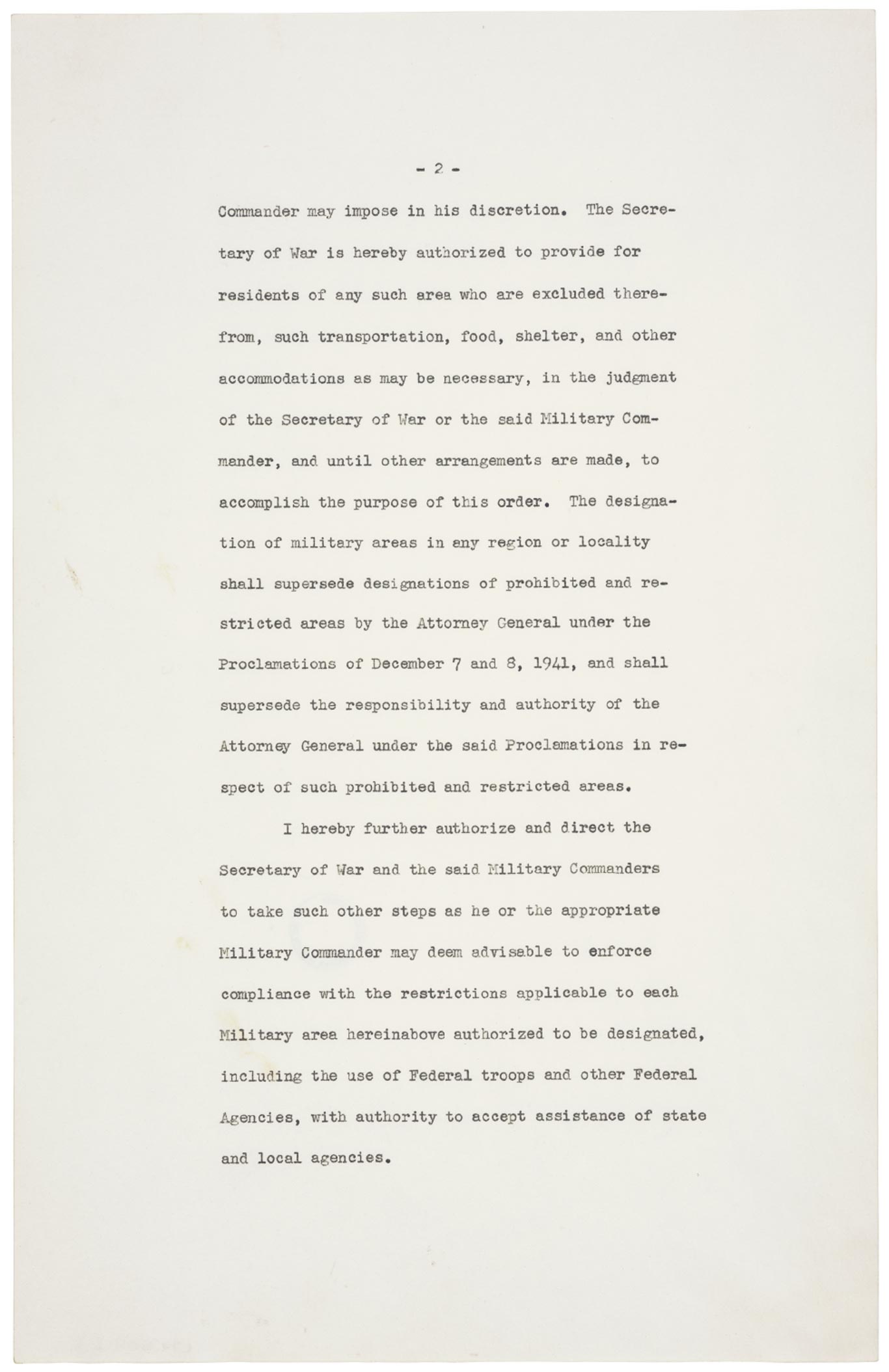

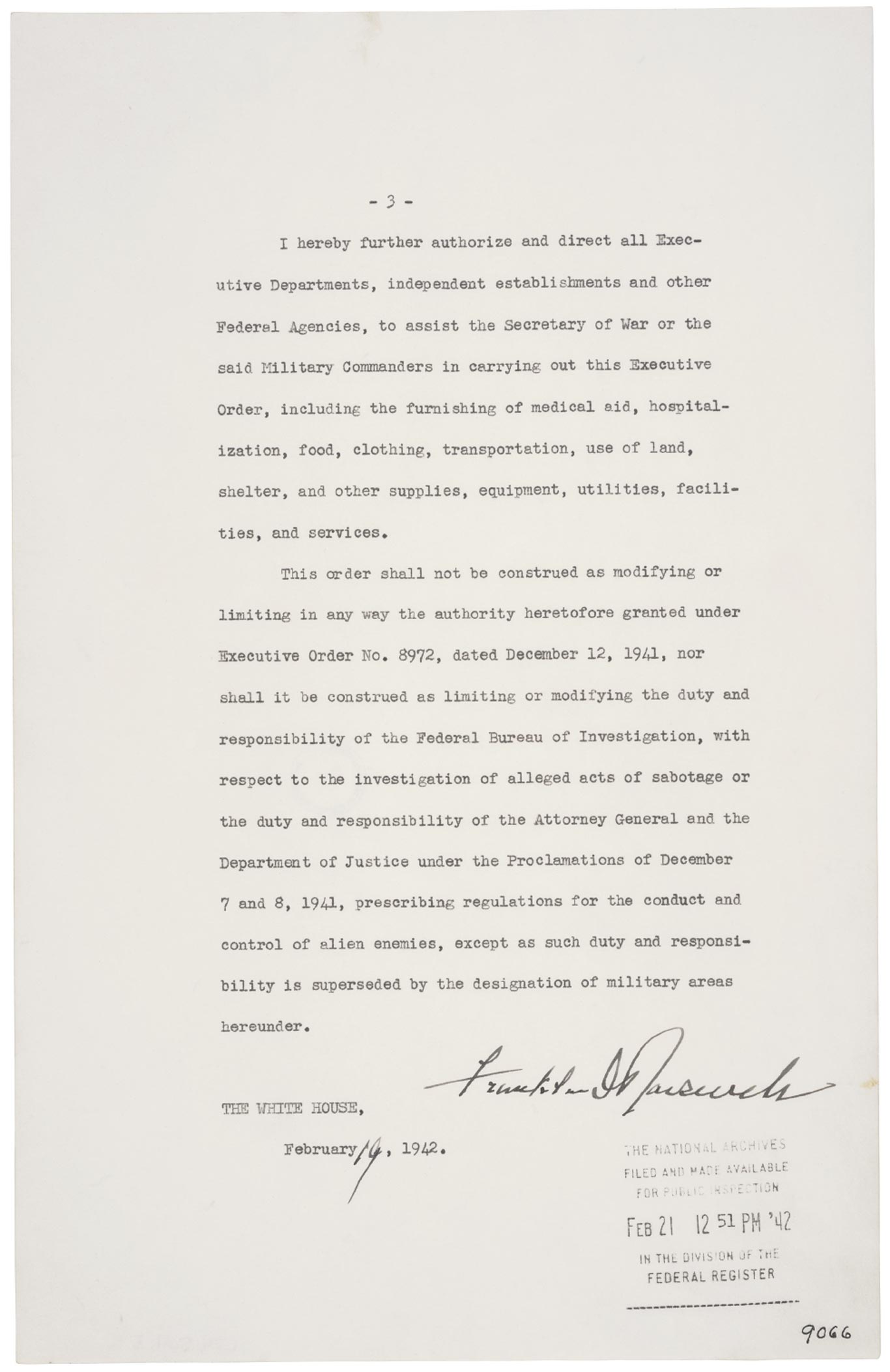

Text 45.02.08 — Executive Order 9066. The order does not mention Japanese Americans. Why do you think they were the only group forced from their homes?

Courtesy of National Archives Catalog. Metadata ↗

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which empowered the US military to determine areas from which anyone could be excluded. Soon thereafter, the military commander of the West Coast designated the western portions of Washington and Oregon, all of California, and the southern part of Arizona off-limits to people of Japanese ancestry.

Officials forced Japanese Americans from their homes despite two prior government reports which found that Japanese Americans were loyal to the United States and posed no national security threat. One of the reports was commissioned in 1941 by President Roosevelt and completed about a month before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. It confirmed Japanese American loyalty to the United States and reassured the president that there was no “Japanese problem” on the West Coast. The report predicted that no armed uprising of Japanese Americans would occur in the event of a war with Japan.

Similarly, an Office of Naval Intelligence study issued in January 1942 corroborated the findings of the earlier investigation and concluded that the “Japanese problem” was exaggerated because of race and recommended that questions of loyalty be handled on an individual basis, not on a racial basis. Despite these findings, Roosevelt still authorized Executive Order 9066.

In the chaotic weeks after the order, Japanese Americans faced uncertainty and anxiety about their future. What would happen to them?

Glossary terms in this module

Alien Land Laws Where it’s used

In 1913, California passed the first such law that prohibited “aliens ineligible to citizenship” from owning or leasing land, a law that targeted Japanese immigrants. From this point on until 1923, many states (Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming) across the US passed similar laws and restrictions.

Executive Order 9066 Where it’s used

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued this order giving US military leaders the power to designate regions of the country as military areas and to exclude anyone from those areas. Although Americans of Japanese descent were not specifically mentioned, this led to them to be mass incarcerated.

Immigration Act of 1924 Where it’s used

A federal law barring immigration to the US from Japan and other Asian countries (except the Philippines, which was then a US colony).

Japantowns Where it’s used

Neighborhoods in cities in the Western United States, like San Francisco or Seattle, which served as the center of Japanese American life and culture before World War II.

Ozawa v. United States (1922) Where it’s used

A Supreme Court decision that determined Japanese people and other Asians were not allowed to become US citizens.

Endnotes

1 Frank J. Taylor, “The People Nobody Wants: The Plight of Japanese-Americans in 1942,” Saturday Evening Post, May 9, 1942, 66.