Module 3: Forced Uprooting and Incarceration

How can an entire racial group be unjustly incarcerated in a democracy?

In this module, you will learn about the frantic weeks West Coast Japanese Americans experienced before they were forced from their homes. You will also learn about the conditions of the camps in which they were imprisoned.

Why is language important when describing historical events such as World War II Japanese American incarceration?

What did Japanese Americans experience in the weeks following the bombing of the military base at Pearl Harbor?

What were the conditions of camp life and how did Japanese Americans adapt to make it more liveable?

Indefinite Detention of Issei Leaders

Five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, two FBI agents arrested Masuo Yasui. He had no idea why they were taking him, where he would go, or how long they would detain him. After Masuo’s arrest, white farmers and businesspeople in Hood River speculated that government officials took him because he was a spy. But that wasn’t true.

Image 45.03.01 — Anxious Japanese Americans feared that the government would shoot or deport the Issei leaders that the FBI had arrested.

Courtesy of Densho, Seattle Times Collection. Metadata ↗

Federal officials imprisoned Masuo Yasui and hundreds of other West Coast Issei community leaders in a detention center at Fort Missoula, Montana. Nearly nine weeks after his arrest, Masuo appeared before a hearing board consisting of prominent local citizens, one of whom was an attorney appointed by the United States Justice Department. They would not release Masuo to rejoin his family. Even if the government had allowed him to return to Hood River, he would have been forced into another camp.

More to explore

Excerpt

We Hereby Refuse

Read in this excerpt from the graphic novel We Hereby Refuse, based on true stories, about how the lives of Jim Akutsu, a Nisei college student in Seattle; his younger brother, Gene; and his mother and father are ruptured after FBI agents arrest Jim’s father.

What’s Next?: Days of Uncertainty

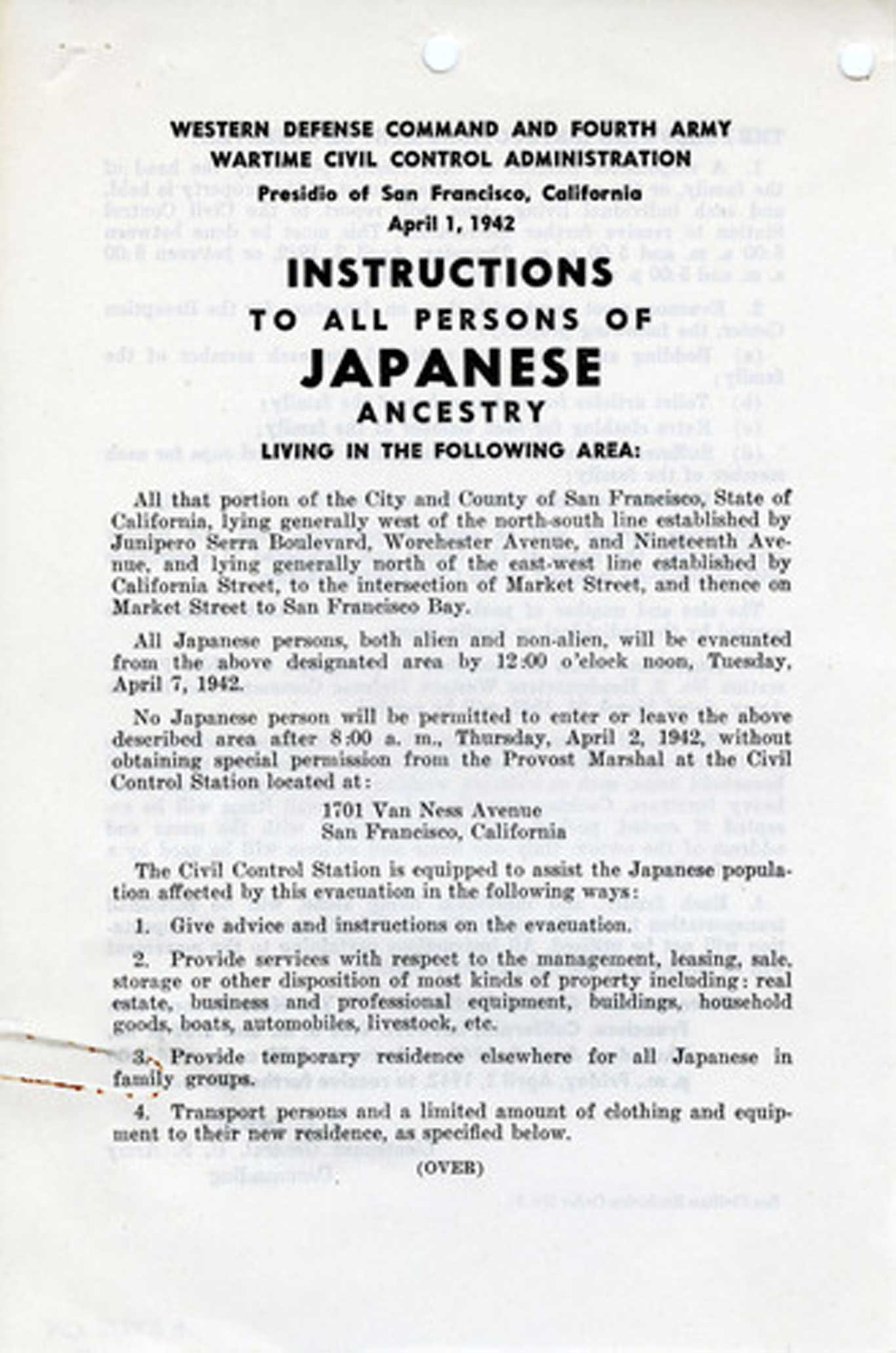

When the FBI had arrested Masuo Yasui, only two of Masuo and Shidzuyo’s children still lived with them: seventeen-year-old Homer and fourteen-year-old Yuka. In early May 1942, they saw signs posted on telephone poles in Hood River. “Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry” was printed in big, bold letters. The signs indicated that Japanese Americans in Hood River had to report to the train station in six days so that the government could transport them to a detention center. They did not know where or how long they would be imprisoned.

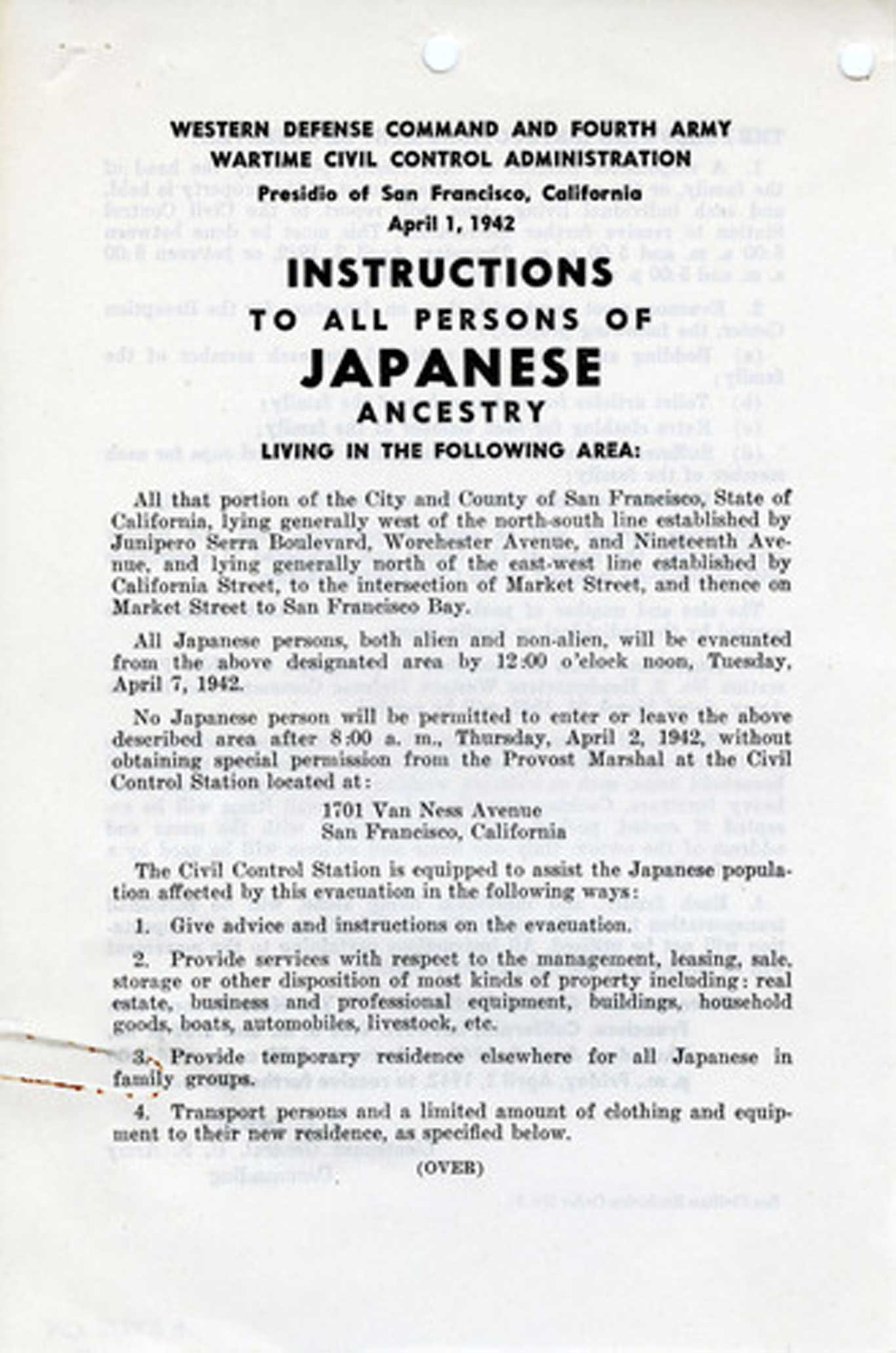

Text 45.03.02 — Signs like this appeared in communities along the West Coast in the spring of 1942 instructing Japanese Americans where to report for transport to government-run camps. The government allowed them to take only what they could carry.

Courtesy of California State Archives. Metadata ↗

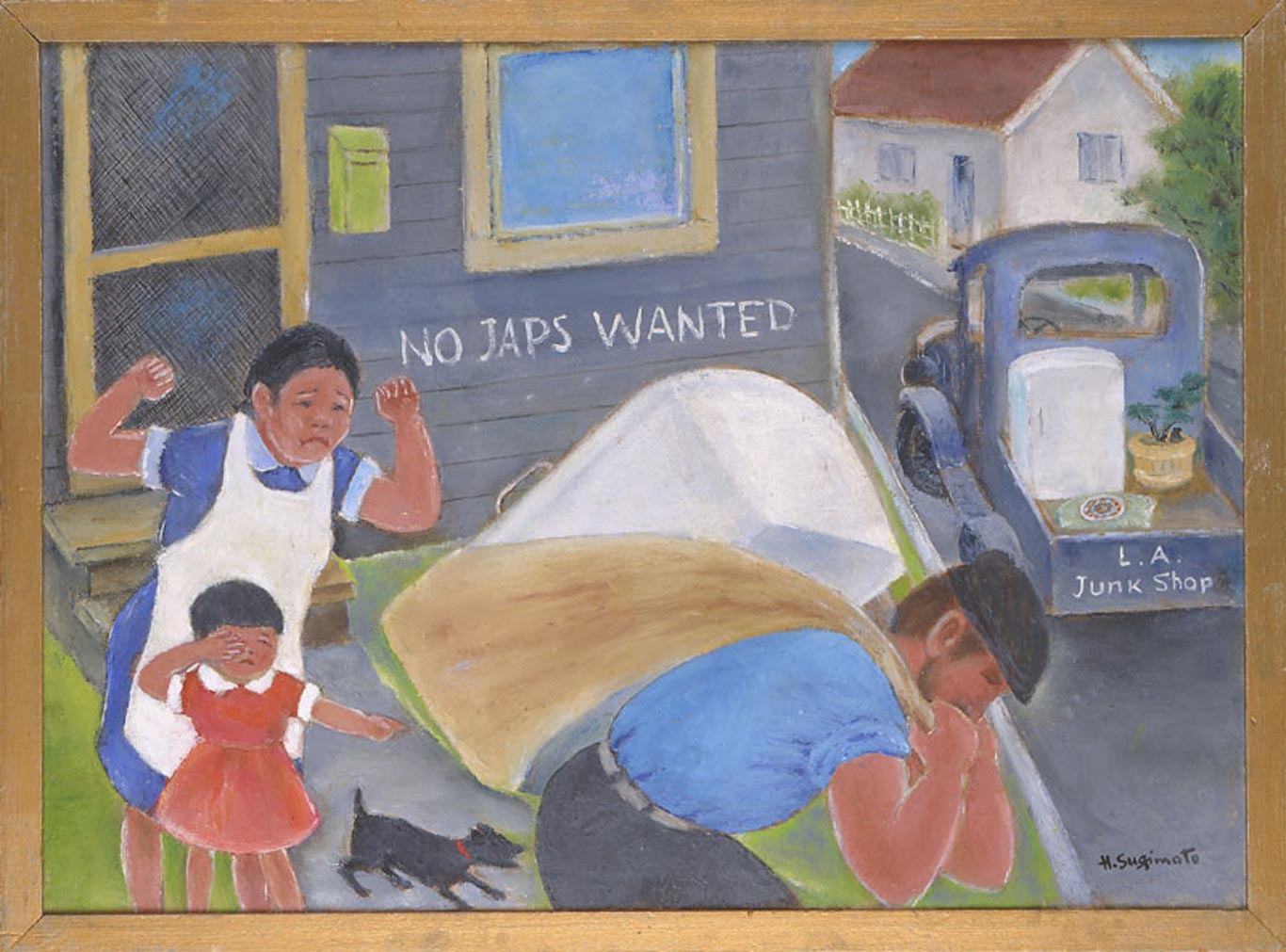

Image 45.03.03 — Japanese Americans had to sell most of their possessions at rock-bottom prices. This painting by Henry Sugimoto, titled Junkshop Man Took Away Our Icebox, captures the emotions of a mother and daughter who must get rid of the family’s belongings.

Courtesy of Japanese American National Museum, Sugimoto (Henry) Collection. Metadata ↗

Text 45.03.02 — Signs like this appeared in communities along the West Coast in the spring of 1942 instructing Japanese Americans where to report for transport to government-run camps. The government allowed them to take only what they could carry.

Courtesy of California State Archives. Metadata ↗

Like the Yasuis, frantic Japanese American families on the West Coast had weeks, sometimes only days, to decide how to close businesses and farms, what to sell, and what to take with them. In the Hood River Valley, some Japanese American farmers who had purchased land prior to the Alien Land Law leased their orchards, but for less than what they owed in annual property taxes. The Yasuis sold much of their land for a fraction of its value.

More to explore

Where to, Now?

On the chilly morning of May 13, 1942, more than five hundred Japanese Americans who had called the Hood River Valley their home, some for decades, gathered at the Union Pacific Station.

Image 45.03.03 — During the spring and summer of 1942, Japanese Americans, like this family in Hayward, California, boarded buses and trains bound for government detention centers. They tied tags with their names and government-assigned family numbers onto their belongings and the clothing they wore.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Metadata ↗

More to explore

Promptly at 10 a.m., armed soldiers told the Japanese Americans to board the trains and drew the blinds. Soldiers stood at the end of each train car. Only one of Homer Yasui’s high school friends was there to wave goodbye when the trains rolled out of the station.

Temporary Detention Centers

The Yasui family rode the train for nearly two days. They were shocked when they arrived on the outskirts of Fresno, California, 750 miles south of Hood River. Their new home was a camp called “Pinedale,” built on eighty acres that had been a lumber yard.

When the Yasuis got off the train, they saw ten-foot-high barbed wire fences surrounding more than two hundred flimsy buildings made of thin wood and tar paper. Guard towers were rooted in each corner of the camp with soldiers pointing guns inward to prevent anyone from leaving. Searchlights swept the camp at night.

Pinedale was one of fifteen temporary prison camps that the government euphemistically called assembly centers. Most were built hurriedly at race tracks, fairgrounds, or livestock pavilions. Japanese Americans lived in horse stalls and hastily constructed barracks.

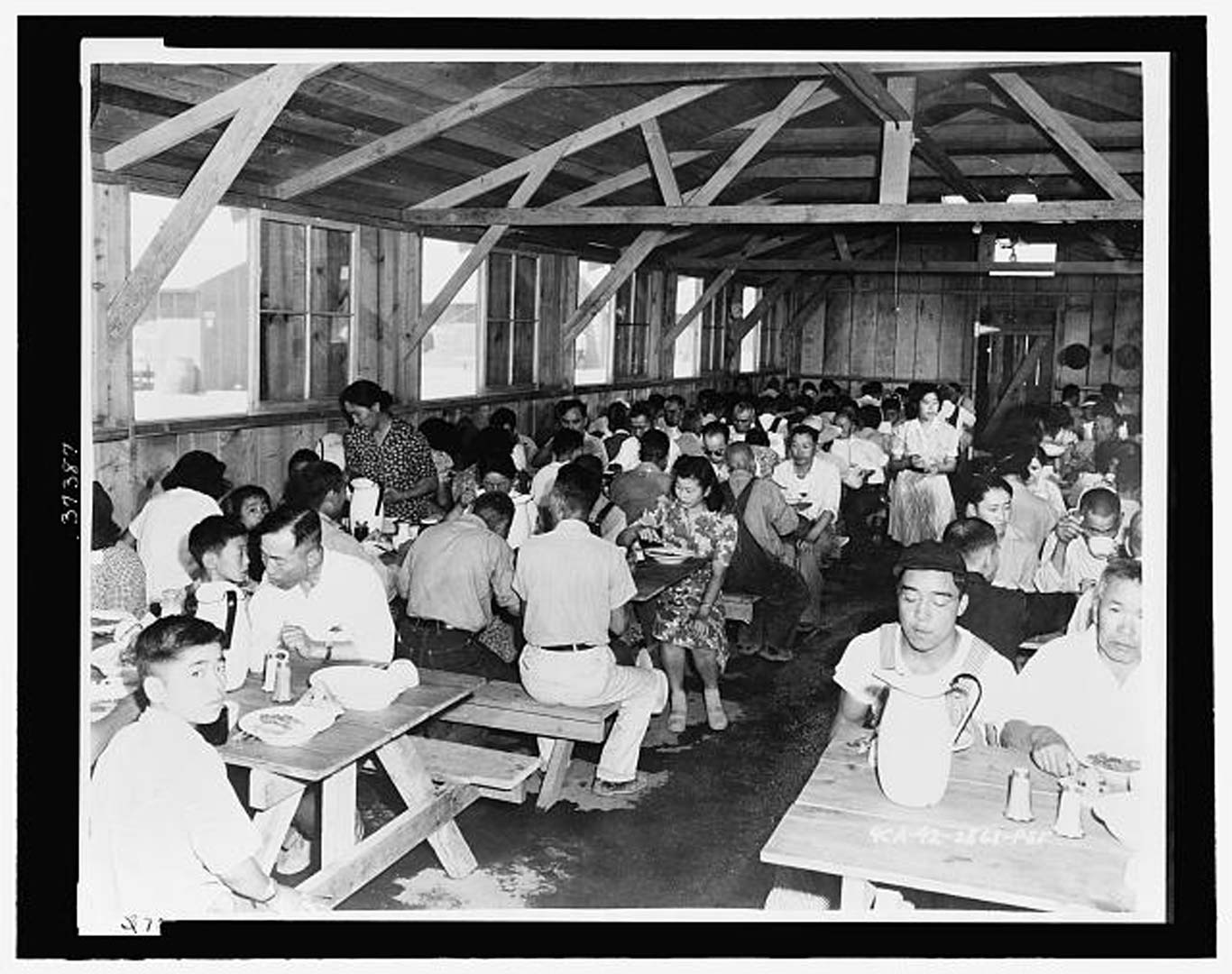

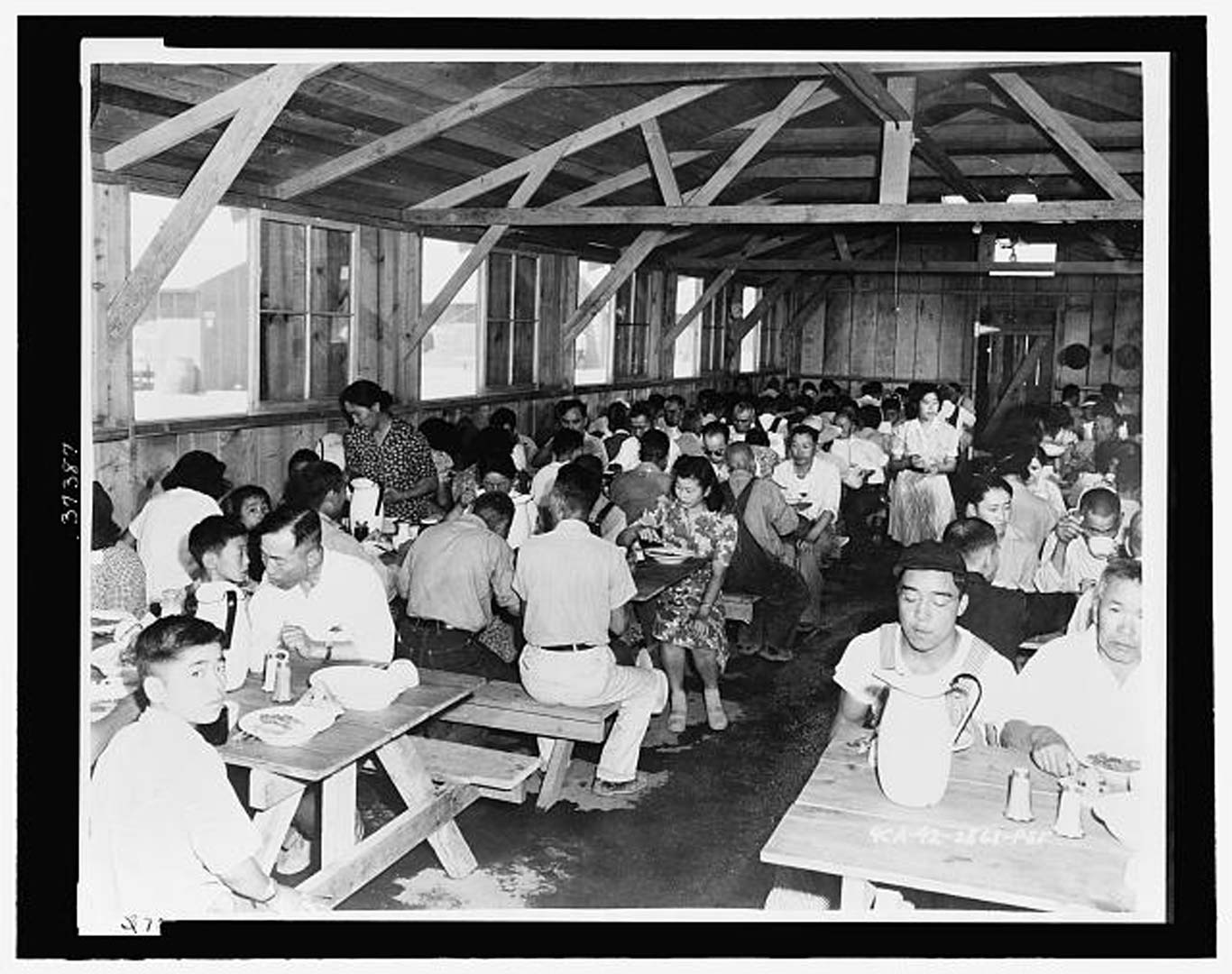

Image 45.03.05 — One of the mess halls at the Pinedale detention center. Eating in mess halls made it difficult to maintain family cohesion.

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Metadata ↗

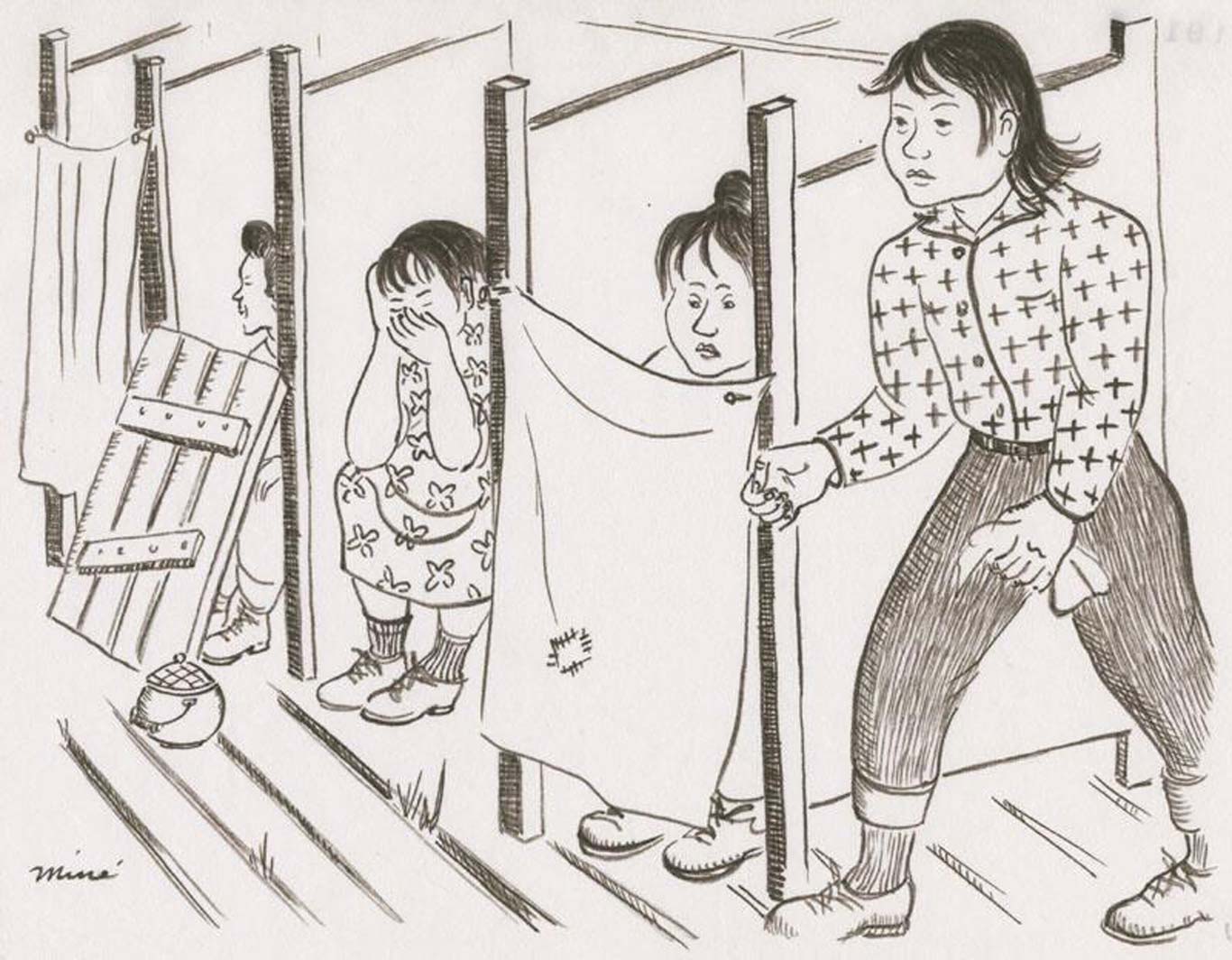

Image 45.03.06 — This drawing by artist Miné Okubo documents a communal bathroom at the Tanforan detention center. Initially, no partitions separated toilets. Former Pinedale inmate Kiyo Sato recalled thinking, “How can I sit in the latrine between all those people, or have my back against a stranger? What am I going to do?”

Courtesy of Japanese American National Museum. Metadata ↗

Image 45.03.04 — One of the mess halls at the Pinedale detention center. Eating in mess halls made it difficult to maintain family cohesion.

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Metadata ↗

Shidzuyo, Homer, and Yuka Yasui set their bags down in the room the government assigned them to share. They saw iron cots on a concrete floor, a single light bulb hanging from a rafter, and thin partitions that did not reach the ceiling. These were the only barriers separating their room from the others in their barrack.

The family’s barrack was part of a larger unit called a “block,” which consisted of forty barracks. Each block had two mess halls and a communal latrine.

Japanese Americans arrived at Pinedale just as the summer heat descended. Temperatures soared beyond 110 degrees, which made daily life a challenge, especially for the majority of inmates who had lived in the temperate climates of Washington and Oregon. People fainted while waiting in the many long lines to take care of basic functions, such as entering the mess hall, using the bathroom, and taking showers. The sizzling temperatures contributed to spoilage that resulted in recurring food poisoning. The heat also melted the asphalt floors in some of the barracks, causing feet to stick and cots to sink into the melting tar.

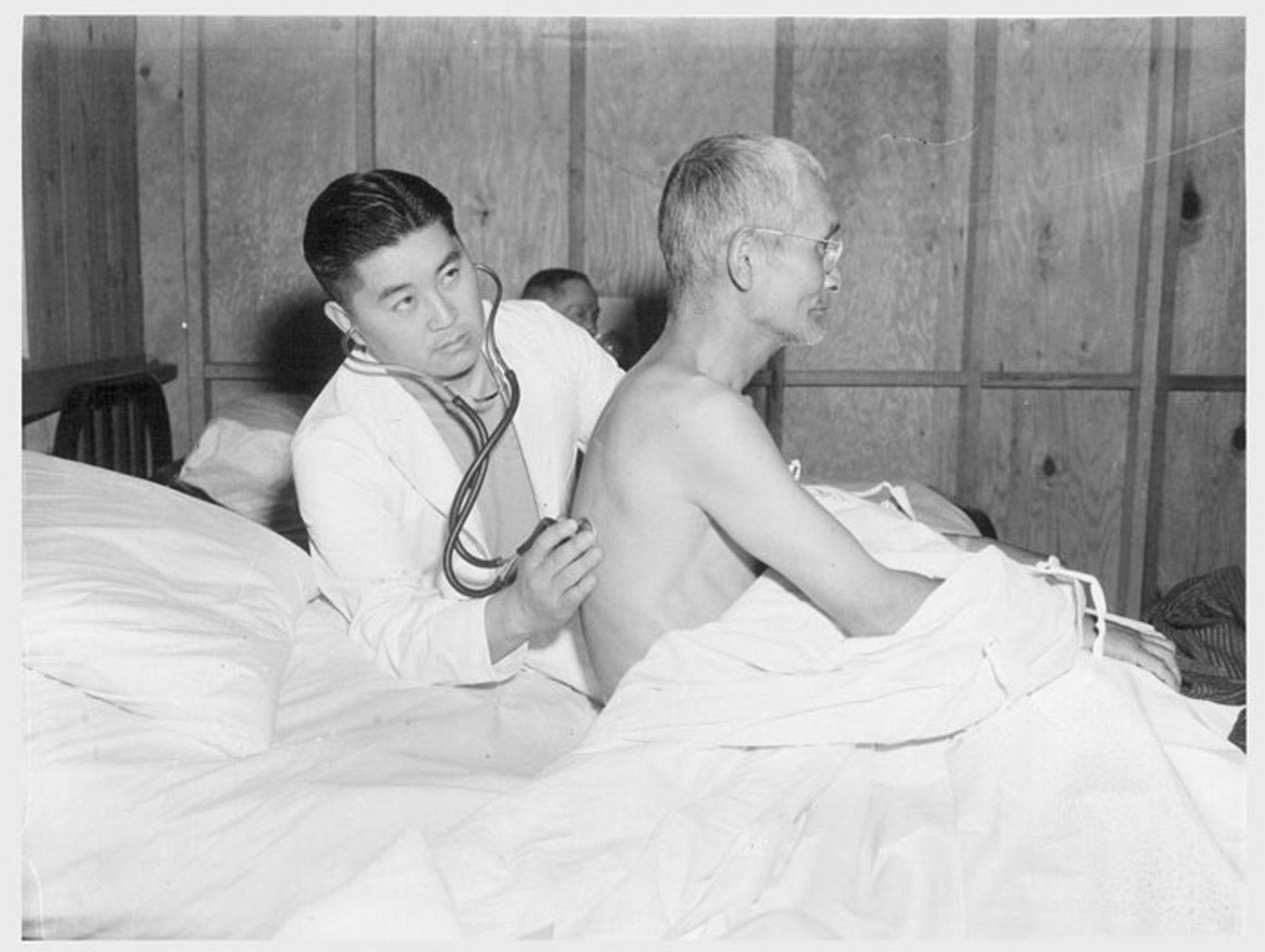

No schools were set up at Pinedale, so teenagers Yuka and Homer had little to do. Yuka spent time with her mother learning how to embroider. Homer played with other teens until Shidzuyo made him get a job. He helped to maintain latrines and worked as an orderly in the camp’s crude hospital which lacked enough staff and medication to deal with health challenges, such as mumps and chickenpox outbreaks resulting from the camp’s dense, unsanitary conditions.

As at other detention centers, administrators at Pinedale established a community council that handled some affairs within the camp. The government allowed only US citizens to be elected to these councils, however, preventing Issei, who were barred from citizenship, from serving. Fresno State College and a local group of ministers donated books for a camp library. Inmates published a newspaper, Pinedale Logger, but the content had to be approved by camp administrators.

Moved Once Again

The government intended the fifteen “assembly centers” to be temporary while a federal agency called the War Relocation Authority (WRA) constructed ten more permanent camps. In July 1942, Pinedale’s 4,800 inmates learned that they had to move once again. Some were sent to a camp called Poston in Arizona, while others, including the Yasui family, were transferred to a camp called Tule Lake built on 1,110 acres in the northeast corner of California.

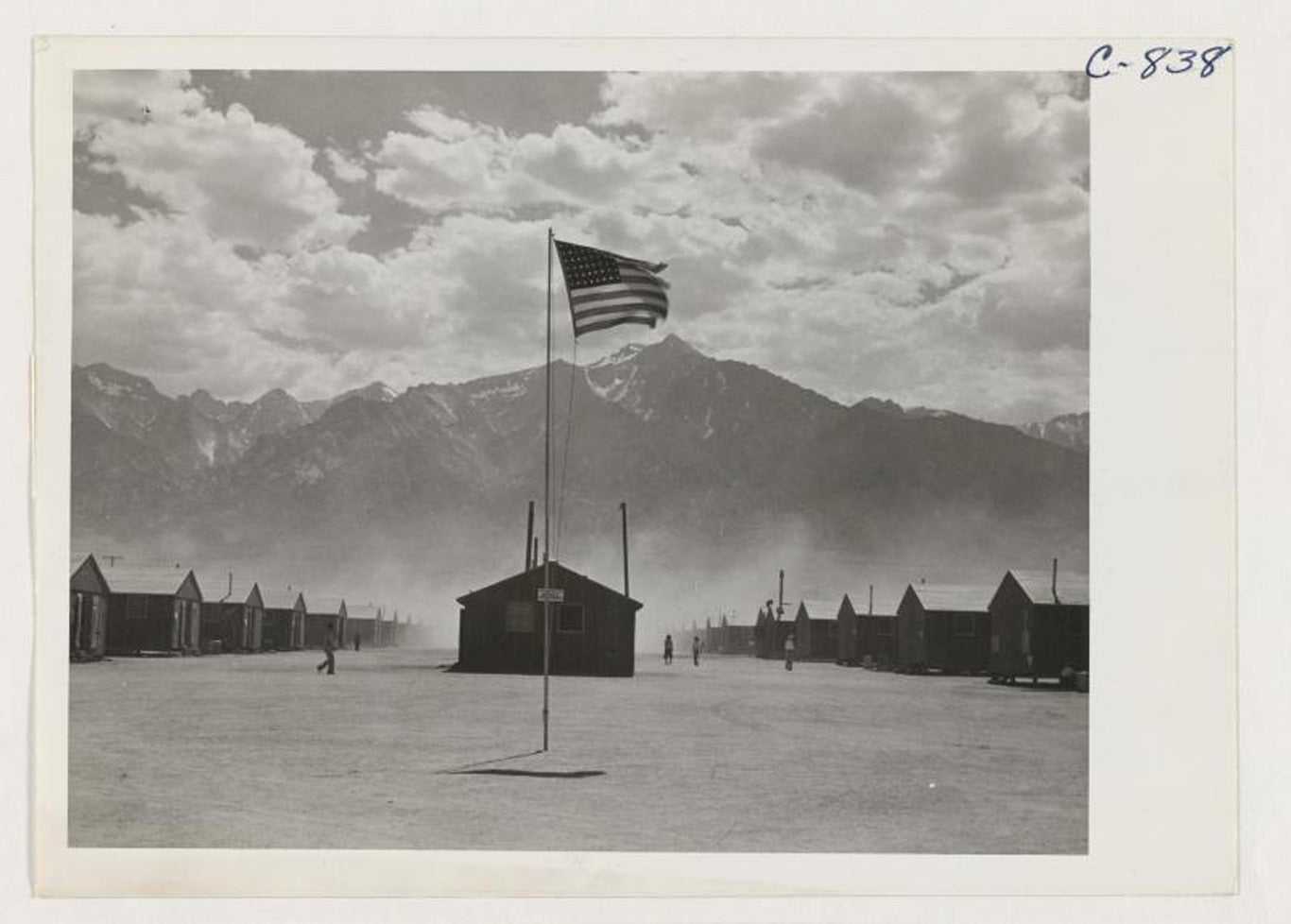

Image 45.03.05 — As at the Manzanar camp, pictured here, wind frequently whipped dust through cracks in the wood of the barracks in many of the camps. The thin tar paper exterior did little to shield inhabitants from severe winter cold and stifling summer heat.

Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library. Metadata ↗

Image 45.03.07b — Bugs were one of the challenges inmates faced at many of the camps. This drawing by artist Miné Okubo captures the annoyance of flying bugs at the Topaz, Utah camp.

Miné Okubo. Bugs at Topaz. Metadata ↗

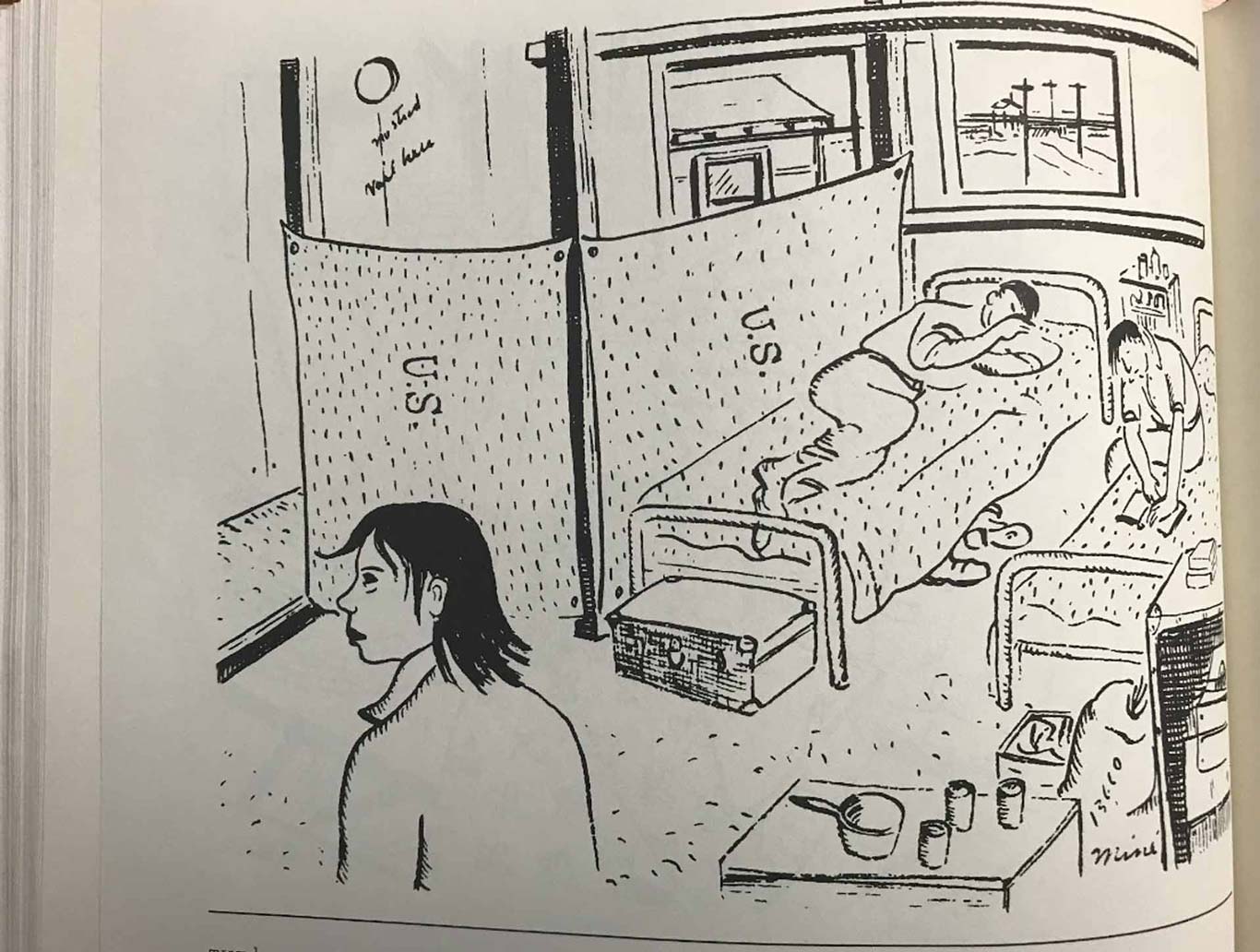

Image 45.03.07c — Artist Miné Okubo drew this illustration of the barrack room in the Topaz, Utah camp that she and one of her brothers shared with a student from California. They hung blankets around Miné’s cot to give her some privacy.

Miné Okubo. Barrack room, Heart Mountain. Metadata ↗

The WRA camps replicated the structure of the “assembly centers,” with tar paper and wood barracks divided typically into four to six rooms. Families or other groupings of up to eight people occupied a room with a stove for heat, a single hanging light bulb, and metal cots. At many of the camps, wind frequently whipped dust through cracks in the wood of the barracks. The thin tar paper exterior did little to shield inhabitants from severe winter cold and stifling summer heat.

Barracks were grouped into “blocks” of twelve to fourteen. About three hundred people lived in each block, which had a mess hall, communal latrine, recreation center, and laundry facility. Barbed wire fencing ringed the camps, punctuated by guard towers staffed by armed soldiers.

Camp Life

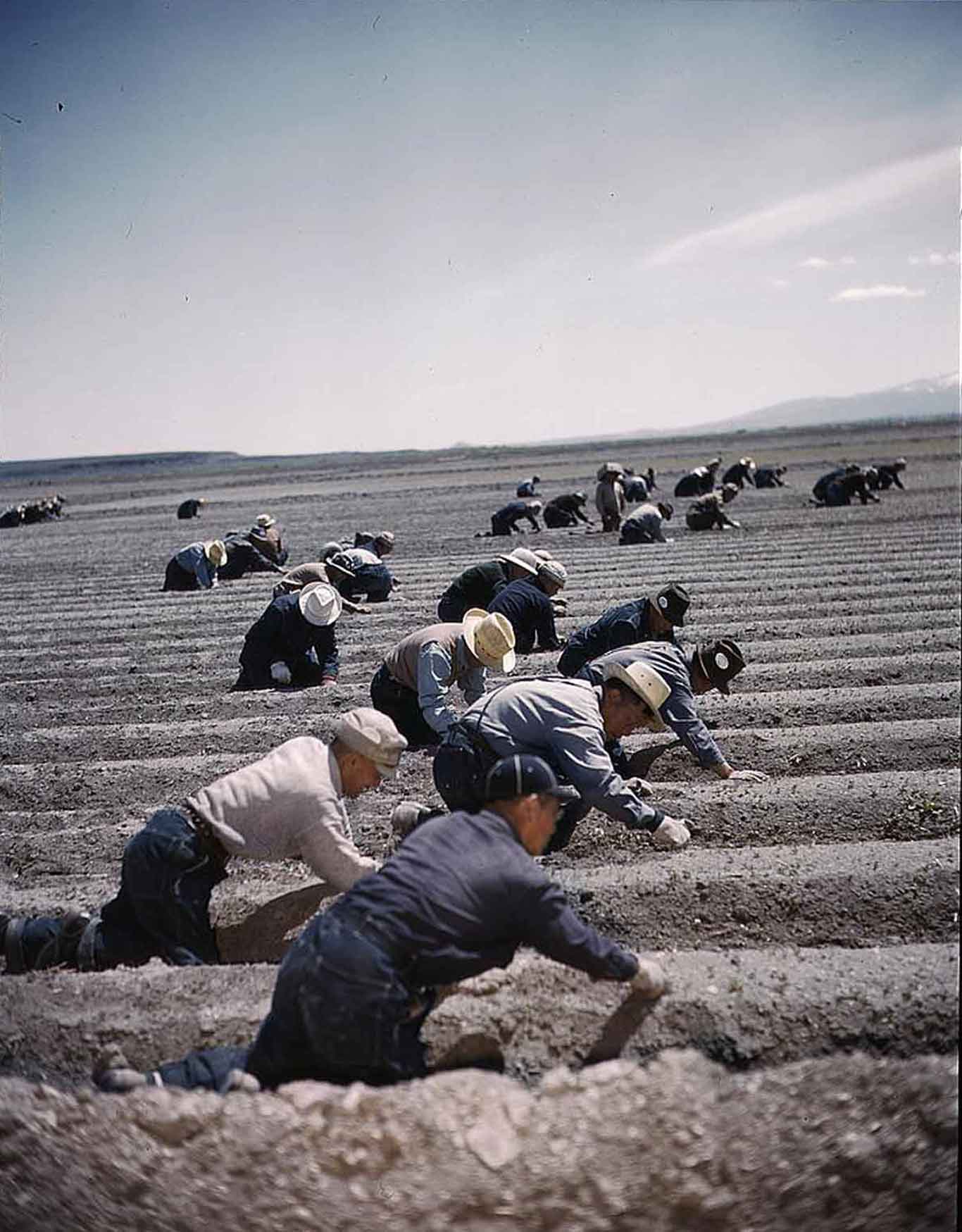

The government intended to detain Japanese Americans in these camps indefinitely, so the WRA set them up to be as self-sufficient as possible. Given wartime food rationing and labor shortages, the WRA put imprisoned Japanese Americans to work within camps.

Inmates farmed nearby agricultural fields and worked in mess halls, hospitals, administrative offices, and other departments to keep the camps running. Ray “Chop” Yasui, one of Masuo and Shidzuyo’s children, served as a “block manager,” which involved distributing supplies, handling mail, and sharing the concerns of block inmates with WRA camp administrators.

Yuka Yasui started attending Tule Lake’s high school as soon as it opened in the fall of 1942. But there were no desks, chairs, books, or supplies at first.

To cope with their confinement, older Japanese Americans engaged in hobbies. Some took art classes taught by fellow inmates. Others joined literary or drama groups. Shidzuyo Yasui, who had trained to teach Japanese arts, taught flower arranging.

Homer Yasui was eighteen when he arrived in Tule Lake. Having graduated from high school, he spent most of his time carousing with other young men, playing baseball, attending dances, flirting with young women, and smoking. Shidzuyo worried that camp life was eroding her youngest son’s sense of responsibility. Families crammed into one room, mass dining, and the lack of privacy in communal bathrooms contributed to the disintegration of family ties.

Shidzuyo was determined to get her youngest children out of the camp as soon as she could. But how would that be possible without Masuo, who was the strict disciplinarian in the family? He was still imprisoned in a special camp for Japanese community leaders. A few weeks before the government forced his family from Hood River, Masuo was transferred from Fort Missoula to another camp at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and then a few months later to Camp Livingston in Louisiana. He would not see most of his family for nearly five years.

Troubles resulting from family separation, disintegration of family cohesion, lack of privacy, and dreadful camp conditions were compounded in subsequent months by the government’s heavy-handed attempt to compel Japanese Americans to declare loyalty to the United States, despite being imprisoned without charges. This led to deep divisions within the camps.

Glossary terms in this module

assembly centers Where it’s used

Japanese Americans were temporarily detained or imprisoned in these facilities until more permanent incarceration camps were created by the War Relocation Authority. It is important to use the term “temporary detention centers” instead of “assembly centers” because it describes the US government’s true purpose, as well as the inhumane living conditions in these facilities. Japanese Americans were not simply gathered or “assembled” into these spaces.

War Relocation Authority (WRA) Where it’s used

The federal agency that managed the imprisonment of Japanese Americans. The word “relocation” inaccurately describes the action as simply moving or relocating to a new home. In reality, Japanese Americans did not have a choice and were forcibly removed from their homes.