Module 4: Cooperation, Resistance, and Dissent

How can an entire racial group be unjustly incarcerated in a democracy?

In this module, you will learn about how the government tried to determine the loyalty of individual Japanese Americans, and the various ways that Japanese Americans responded with cooperation, resistance, and dissent to the government’s changing demands on them.

Why did the US government want to differentiate between “loyal” and “disloyal” prisoners in Japanese American incarceration sites?

How did Japanese Americans express their dissent to the government’s efforts to assess their loyalty?

Who’s “Loyal”?

Imprisoned without any evidence of being disloyal or a military threat, Japanese Americans began complaining about inhumane conditions in all the War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps during their first months of operation. Inconsistent and harsh administrators, as well as policies that privileged Nisei over Issei for leadership in camp self-governance, aggravated existing political and generational disagreements among camp inmates. This resulted in uprisings and strikes at the Manzanar, California, and Poston, Arizona, camps in late 1942.

News accounts characterized these events as evidence of Japanese American disloyalty. Those charges, along with accusations that the WRA was coddling inmates, and opposition to the WRA’s intention to resettle Japanese Americans outside the camps, prompted congressional investigations.

Text 45.04.01 — This Los Angeles newspaper account of protests at Manzanar characterized the incarcerees as disloyal to the United States.

Courtesy of Yale University Library, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Metadata ↗

Around the same time, the US Department of War decided to form an all-Nisei combat team recruited from Hawaiʻi and the WRA camps. The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), an organization of staunchly pro-American Nisei, advocated for such a unit for Japanese Americans to prove their loyalty. The War Department created a questionnaire to determine the loyalty of potential soldiers. In early 1943, military recruiters, armed with the questionnaire, visited the ten WRA camps. About 1,200 young Nisei men volunteered. They joined nearly ten thousand Japanese American volunteers from Hawaiʻi to form the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which fought in Europe during World War II.

More to explore

Video

3:37

Why Did the JACL Urge Cooperation?

Bill Hosokawa Interview Segment 2 – Leaders of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), an organization of Nisei, urged Japanese Americans to cooperate with the government during World War II to demonstrate loyalty to the United States. Under the leadership of Mike Masaoka, who became the organization’s Executive Secretary in 1941, the JACL adopted an aggressive pro-American stance to counter accusations that Japanese Americans had divided loyalties between the United States and Japan. Before and after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, JACL leaders collaborated with the military, FBI, WRA, and other government agencies, and identified Issei they considered potentially disloyal. Masaoka also advocated that the military draft Nisei men so that they could prove their loyalty to the United States. Many Japanese Americans harshly criticized the JACL for not standing up for their rights and accused JACL leaders of selling out. In this video, Bill Hosokawa, a longtime columnist for the JACL’s newspaper, discusses why the JACL urged Japanese Americans to cooperate with the government.

Video

5:48

Why Did the JACL Urge Cooperation?

James Omura Interview Segment 7 – Leaders of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), an organization of Nisei, urged Japanese Americans to cooperate with the government during World War II to demonstrate loyalty to the United States. Under the leadership of Mike Masaoka, who became the organization’s Executive Secretary in 1941, the JACL adopted an aggressive pro-American stance to counter accusations that Japanese Americans had divided loyalties between the United States and Japan. Before and after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, JACL leaders collaborated with the military, FBI, WRA, and other government agencies, and identified Issei they considered potentially disloyal. Masaoka also advocated that the military draft Nisei men so that they could prove their loyalty to the United States. Many Japanese Americans harshly criticized the JACL for not standing up for their rights and accused JACL leaders of selling out. In this video, journalist James Omura provides a perspective critical of the JACL and Mike Masaoka.

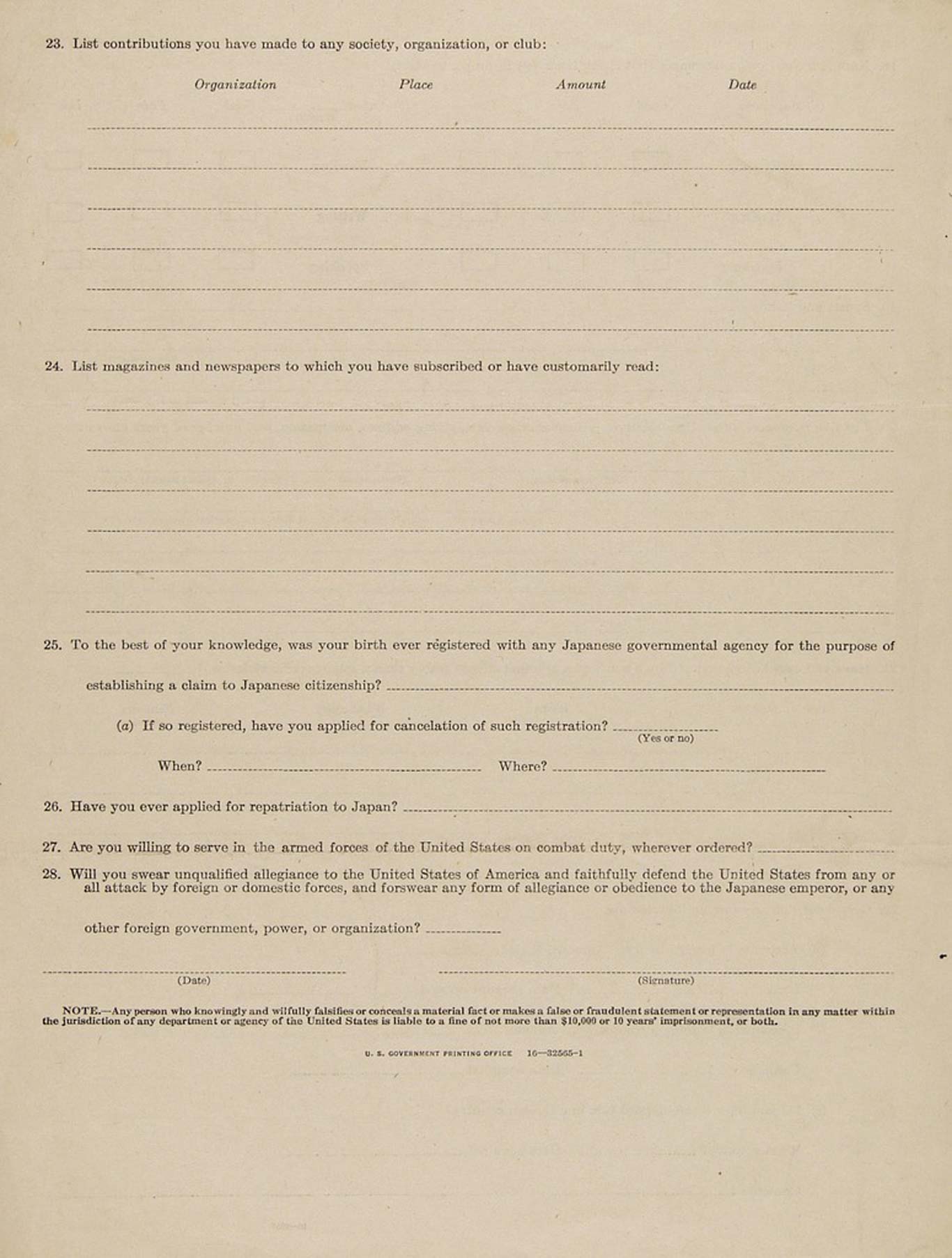

WRA officials, eager to integrate Japanese Americans into white society, adopted the military’s questionnaire to determine which inmates would be allowed to leave the camps. The WRA required all inmates older than seventeen to complete the questionnaire, which it called an “Application for Leave Clearance.” Inmates’ responses guided camp administrators’ decisions about whether individuals would be eligible to leave the camps for colleges or jobs in Midwestern or Eastern states.

Problem Questions

But two questions generated confusion and resentment among many inmates. One asked about willingness to serve in the armed forces and the other asked respondents to forswear allegiance to Japan and to swear unqualified allegiance to the United States.

Many incarcerated men were wary of answering “yes” to the first question, unsure of whether a positive response would mean automatic induction into the army. The second question was also troubling. Answering “yes” could imply that people had previously been loyal to Japan. In addition, Issei, who were not allowed to become US citizens at the time, feared that answering “yes” might mean renouncing their Japanese citizenship, leaving them stateless.

Text 45.04.02 — Questions 27 and 28 on this mandatory government questionnaire generated confusion, anger, and frustration among many incarcerees.

Courtesy of Densho. Metadata ↗

The vast majority of incarcerees answered “yes” to both questions. But about seven percent answered “no.” Some were outraged that the government imprisoned them when they had done nothing wrong, only to then question their loyalty. Others answered “no” because they were disillusioned about losing their constitutional rights. About six percent refused to answer or qualified their responses, explaining that they would answer “yes” to both questions if they were freed. But the government only allowed “yes” or “no” responses, and considered all “no” responses as proof of disloyalty. The government decided to imprison everyone who answered “no” in a single high-security camp.

New Role for Tule Lake

At the Tule Lake camp in California, there was widespread confusion and anger about the questionnaire. The camp’s director tried to force people to complete the form, even if they objected to it. As a result, Tule Lake had the largest percentage of inmates who refused to respond to the “loyalty” questions or answered “no.” This had dire consequences.

In June 1943, WRA officials designated Tule Lake as a “segregation center” for inmates from all of the camps who had answered the loyalty questions negatively. The government transferred about 6,500 Tule Lake inmates who had responded “yes” to the loyalty questions to other camps. And it moved twelve thousand people who had responded “no” from the nine other camps to Tule Lake.

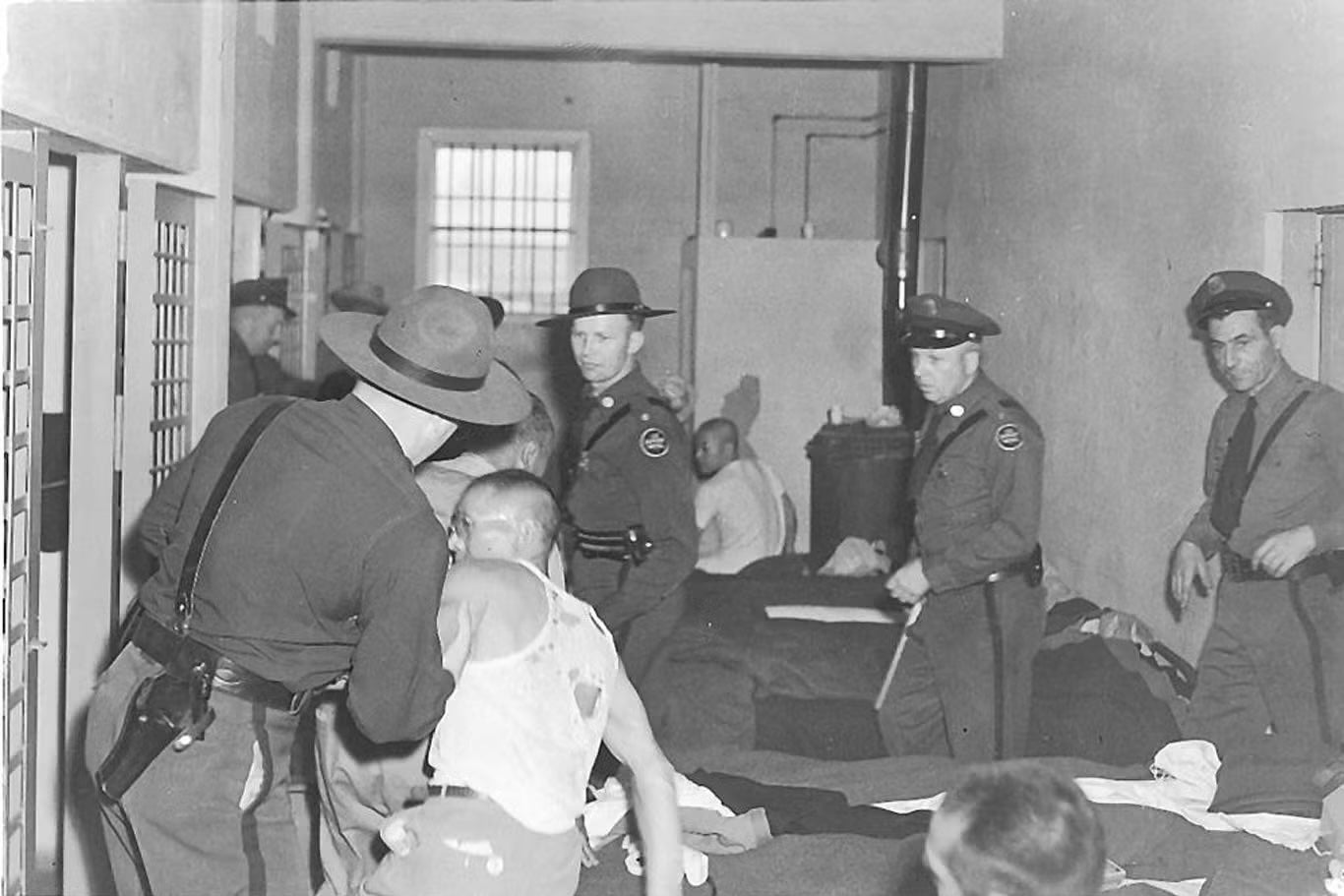

Army tanks rolled into Tule Lake. Twenty-two guard towers were added, and a battalion of one thousand military police was activated. Then, after a strike by Tule Lake inmate farmworkers that began in October 1943 because of poor safety conditions, the camp’s director declared martial law and called in the military. They arrested and jailed about four hundred men, whom camp administrators suspected of fomenting dissent, in a stockade. Some men were imprisoned for eight months with no charges or hearings.

Image 45.04.03 — At Tule Lake, the government built a prison within the prison camp to jail men considered dissident leaders.

Courtesy of Discover Nikkei. Metadata ↗

Tensions mounted within the camp. On one side, disillusioned Issei, Kibei (Nisei who were raised in Japan), and others advocated that Tule Lake prisoners repatriate to Japan, the only nation where they could envision having a future. Camp officials allowed them to form pro-Japan groups to prepare for eventual settlement in that country. Members of these groups clashed with the other Japanese Americans who disagreed or tried to remain neutral.

Reacting to the turmoil at Tule Lake, President Roosevelt signed unprecedented legislation that allowed Japanese Americans to renounce their US citizenship. Elders who wanted to return to Japan compelled their teenage and young adult children to surrender their citizenship, believing that families would be separated if not all members renounced. Others renounced to protest the racism and discrimination they experienced, and the government stripping them of fundamental rights. Still others were intimidated by violence and peer-pressure that advocates for renunciation used to coerce undecided Nisei. By March 1945, more than five thousand Nisei had renounced their citizenship.

More to explore

Excerpt

Confusion, Fear, and Frustration Lead to Renunciation of Citizenship

This excerpt from the graphic novel We Hereby Refuse depicts the real-life story of Hiroshi Kashiwagi, a young Nisei from the Sacramento area, who renounced his citizenship [pages 102, 124,126].

Opportunities to Leave the Camps

Meanwhile, in the other camps, the WRA encouraged Japanese Americans who had answered “yes” to the loyalty questions to leave the camps for schools and jobs in the Midwest and East Coast. As early as the spring of 1942, even as the military was forcing Japanese Americans from their homes into camps, the WRA wanted to disperse Japanese Americans throughout the country so that they would assimilate into white society and not cluster like they did in pre-war Japantowns. WRA officials also did not want Japanese Americans to become dependent on the government, as was the case in the camps, for basic necessities. In addition, WRA leaders wanted the camps closed as soon as possible because they were seen as too costly to operate and were a blight on a country purportedly fighting to preserve democracy.

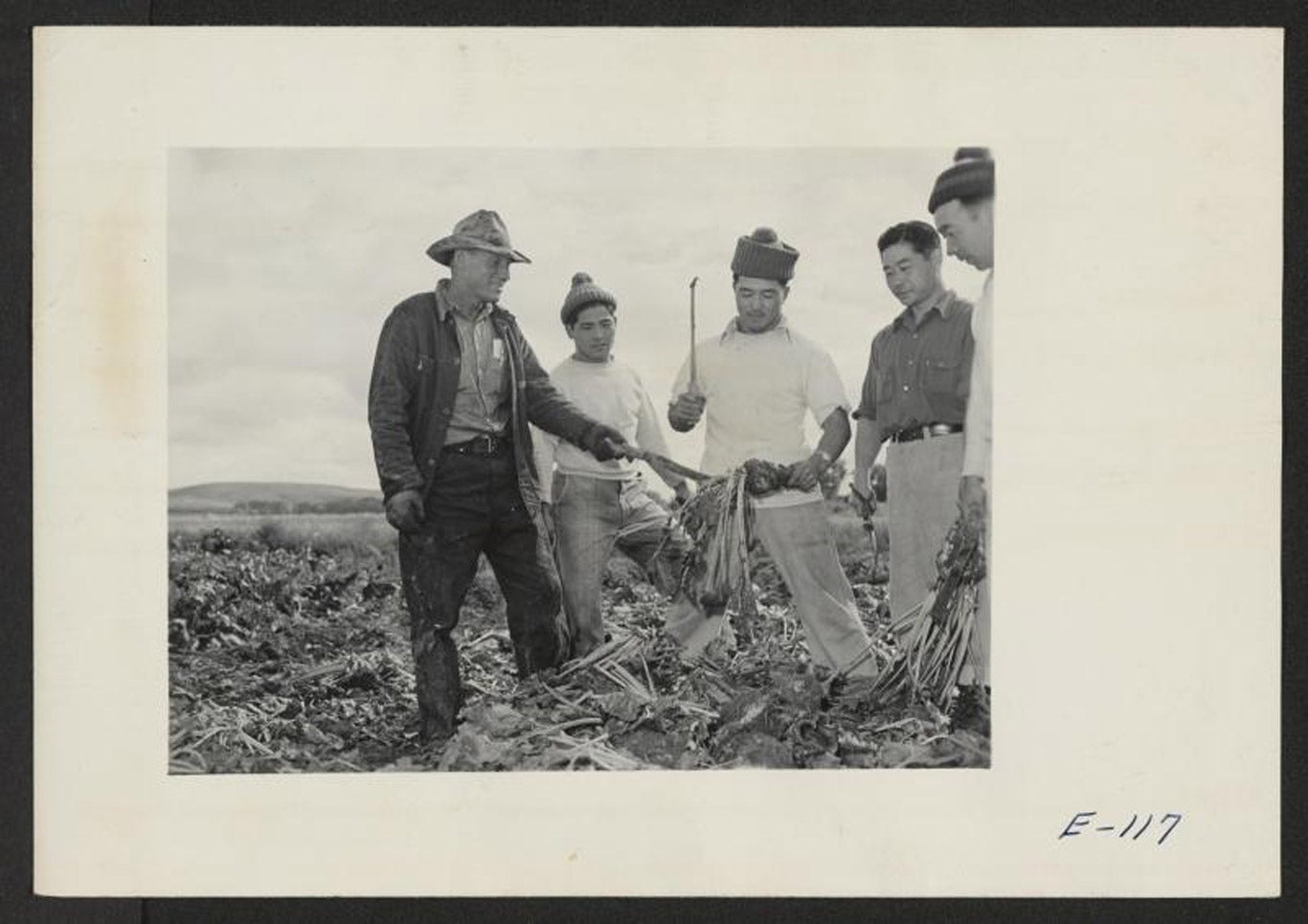

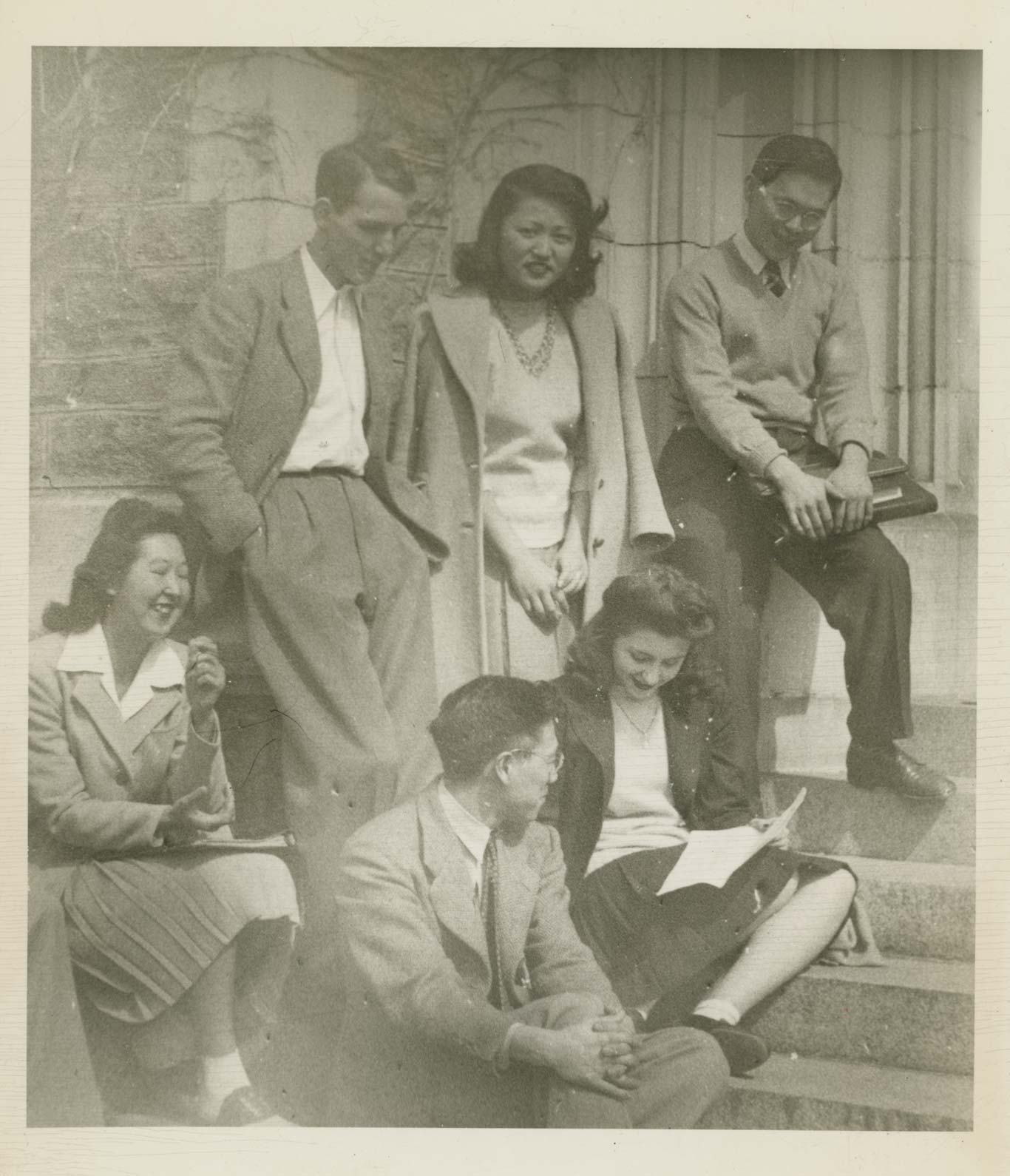

Even before incarcerees had to answer the “loyalty” questions, the WRA released some Japanese Americans from the camps. Due to wartime labor shortages, the WRA granted seasonal leaves for Japanese Americans to work in agricultural fields. Two hundred fifty Nisei were allowed to leave camps by December 1942 to attend colleges outside the exclusion zone. Among them was Homer Yasui, who left Tule Lake for the University of Denver. Several months later, his younger sister Yuka Yasui left Tule Lake bound for Denver to attend high school.

In the spring of 1943, Yuka and Homer’s eldest brother, Ray “Chop” Yasui, secured a year-long “seasonal pass” from the camp, which allowed him, his wife, and their young child to leave Tule Lake for a farm near Great Falls, Montana. In May 1943, Tule Lake administrators allowed Chop, Homer, and their mother, Shidzuyo, to leave for Denver.

The initial process to apply for educational or work leaves was cumbersome. The “loyalty questionnaire” was the WRA’s attempt to streamline the process. Answering “yes” to the loyalty questions was the first step for nearly 35,000 people, mostly young and educated Nisei, to leave the camps.

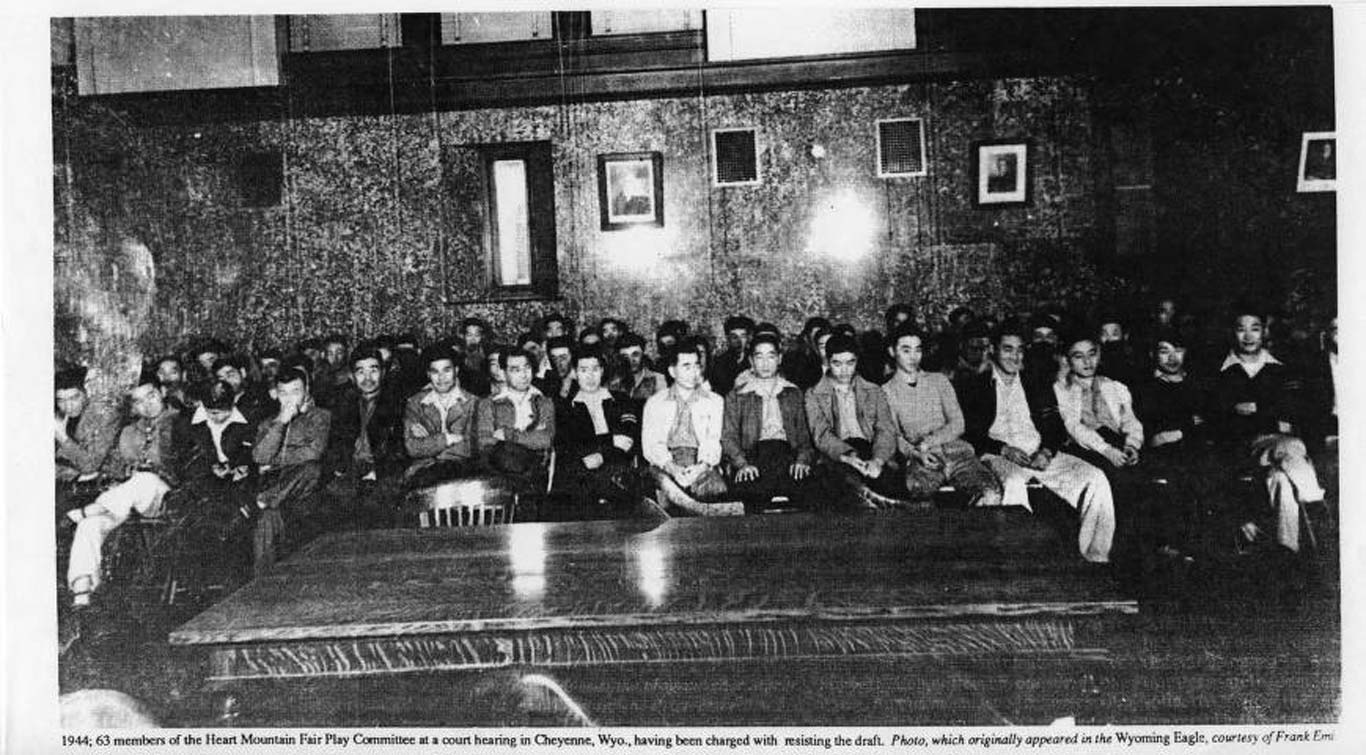

Protests Against Conscription

In early 1944, the army announced that Nisei men would be eligible for the draft. At the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming, a group of young men organized the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee. They were US citizens who were willing to join the army, but they wanted their citizenship rights restored first. Without a promise from the government that they would regain their rights, members refused to report for the required physical exams. Because they resisted the draft, they were tried as a group, convicted, and jailed.

Image 45.04.05 — Government agents arrested sixty-three Nisei men incarcerated at the Heart Mountain, Wyoming, camp who resisted the military draft to protest the loss of their constitutional rights.

Courtesy of CSUDH, Geth Archives and Special Collections. Metadata ↗

More to explore

Excerpt

Resisting the Draft on Principle

This excerpt from the graphic novel We Hereby Refuse chronicles Jim and Gene Akutsu’s decisions to resist the draft, their subsequent trials, and imprisonment. [pages 110-117].

Legal Challenges to Wartime Orders

A few Japanese Americans filed lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of policies targeting Japanese Americans. One of them was a member of the Yasui family, attorney Minoru “Min” Yasui. Working in Portland, Oregon, he purposely defied the curfew for Japanese Americans and insisted on being arrested so that he could legally challenge that restriction on Japanese Americans.

Nearly two hundred miles north in Seattle, Gordon Hirabayashi, a senior at the University of Washington, believed that the curfew and forced removal orders targeting Japanese Americans were unconstitutional, and he refused to comply.

In Oakland, California, twenty-three-year-old welder Fred Korematsu wanted to stay in the Bay Area with his Italian American girlfriend. He refused to obey the government’s orders.

Police arrested all three men. All three filed lawsuits. The US Supreme Court ruled against them.

The high court, however, ruled in favor of Mitsuye Endo, a young Nisei woman who sued the government for indefinitely imprisoning Japanese Americans whom the government considered “loyal.” President Roosevelt, anticipating the court’s ruling, rescinded the order excluding Japanese Americans from the West Coast the day before the justices announced their unanimous decision in October 1944.

It soon became clear that the nearly 80,000 Japanese Americans still in the camps, as well as the thousands who had moved to midwestern and eastern states, could return to the West Coast. But with no homes or jobs there to return to, what would they do?

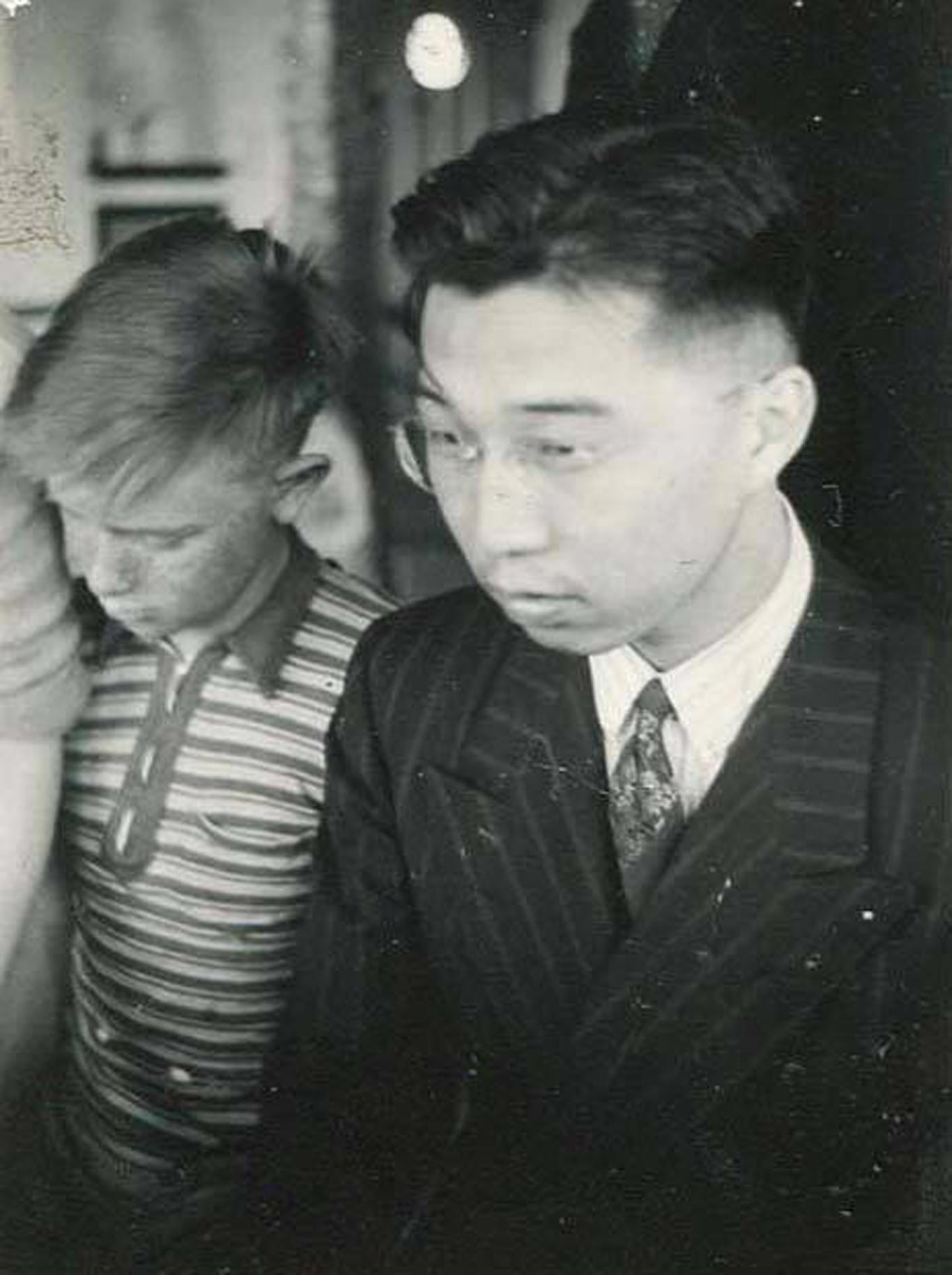

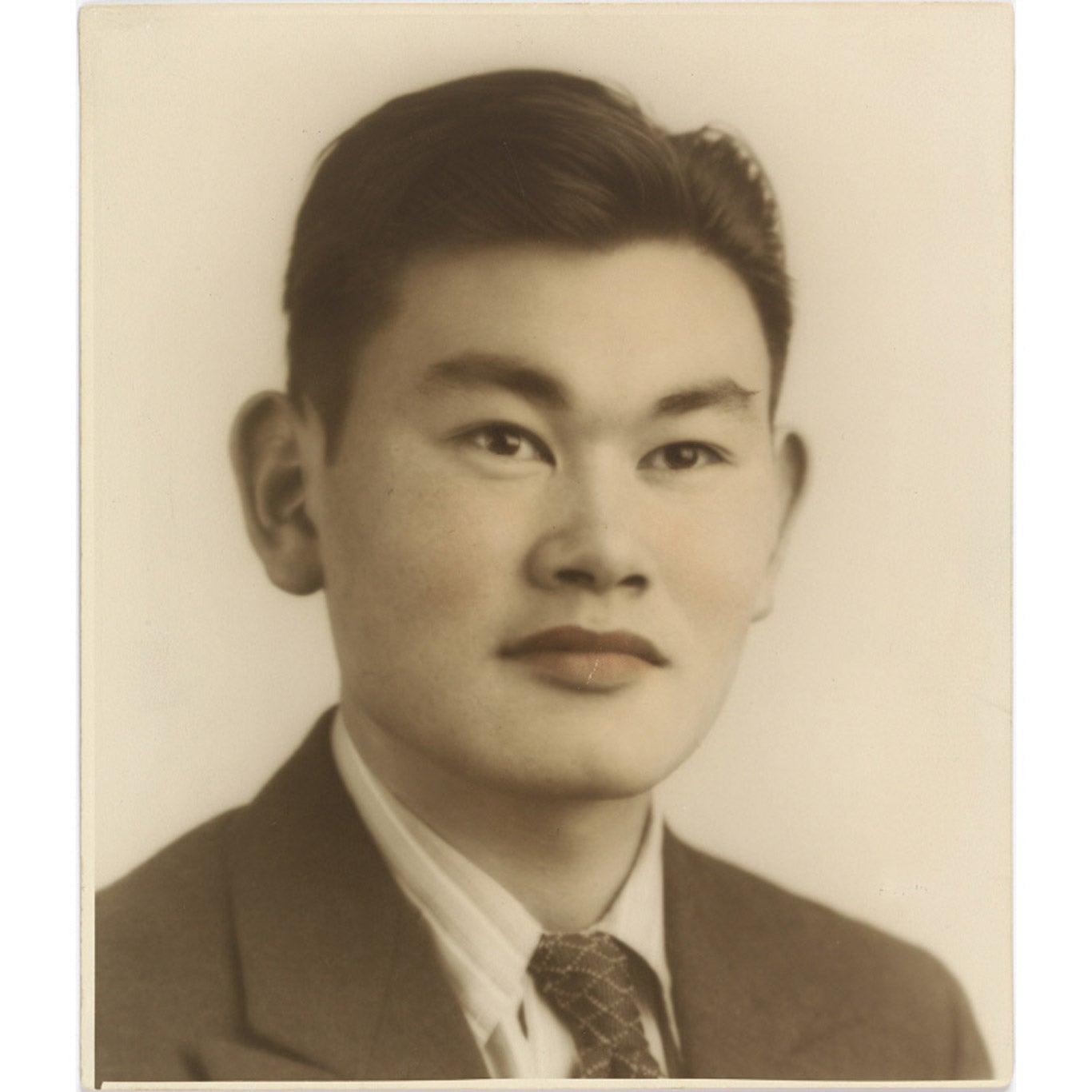

Image 45.04.06. 45.04.07, 45.04.08, 45.04.09 — From left to right, top to bottom: Min Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Mitsuye Endo brought lawsuits challenging government violations of Japanese Americans’ civil liberties.

Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Metadata ↗

Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries. Metadata ↗

Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Metadata ↗

Courtesy of California State University, Sacramento. Library. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Metadata ↗

Glossary terms in this module

democracy Where it’s used

A way of governing in which the people of a nation or state have a voice in developing laws or electing officials to create laws for them. Democracy is a fundamental principle of the US government, influenced by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, made up of Indigenous nations that gathered in what is now known as New York, and European philosophers.