Module 5: Starting Over

How can an entire racial group be unjustly incarcerated in a democracy?

In this module, you will learn about the closure of the camps, how Japanese Americans rebuilt their lives, and the changing perceptions of Japanese Americans in the two decades following World War II.

Why did the government decide to close the camps?

What economic, political, and societal trends and conditions affected Japanese Americans upon leaving camps?

What were some of the “strategies for survival” Japanese Americans used to rebuild their lives?

The Decision to Close the Camps

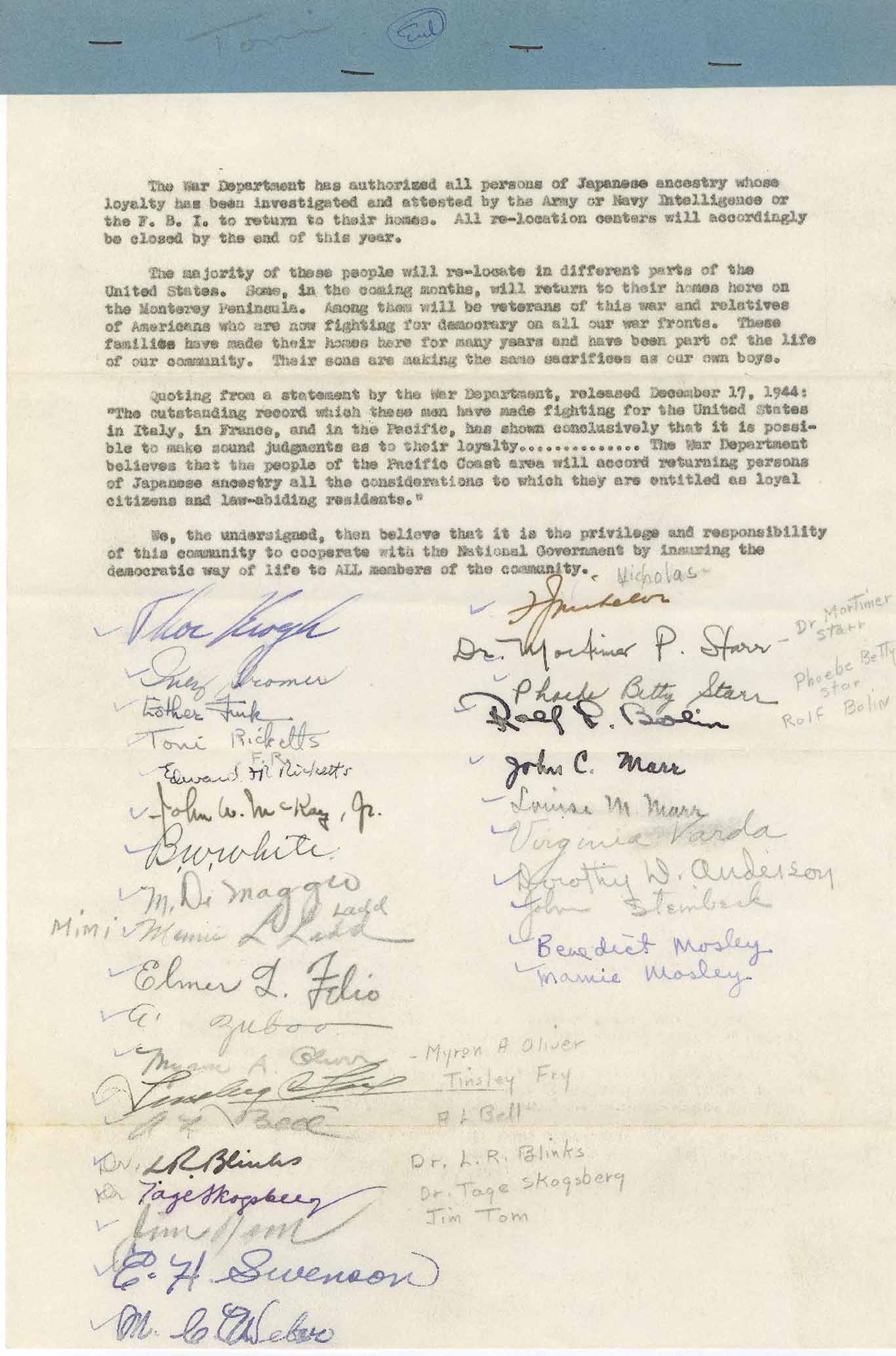

By 1944, the war in the Pacific had clearly turned in favor of the United States and its allies. Even military leaders privately acknowledged that excluding Japanese Americans from the West Coast was unnecessary. That spring, War Relocation Authority (WRA) and Department of the Interior officials advocated closing the camps because continued detention was unnecessary and harmful to Japanese Americans. President Roosevelt, however, waited until after the November 1944 presidential election to announce plans to close the camps. He did not want to upset Pacific state voters who still vilified people of Japanese ancestry and did not want them moving back.

On December 17, 1944, the Department of War announced that Japanese Americans could return to the West Coast effective January 2, 1945. The WRA then announced that all the camps under its jurisdiction would close by the end of 1945.

More to explore

Image

Closing the Camps

Although the WRA intended to close the camps it administered by the end of 1945, the camp at Tule Lake remained open until March 1946. Three other camps, run by the Department of Justice, remained open after 1945. Those camps housed people who had renounced their citizenship at the Tule Lake camp, as well as some of the Issei community leaders that government agents had arrested soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Masuo Yasui was one of them. The government finally released him from a camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico in January 1946. A Department of Justice camp at Crystal City, Texas, pictured here, housed German and Japanese immigrants and their families, as well as hundreds of Japanese Latin Americans and German Latin Americans expelled from their countries at the request of the United States.

Returning to the West Coast

More than two-thirds of the eighty thousand Japanese Americans still living in the WRA camps at the beginning of 1945 decided to return to the West Coast. But most had no homes or jobs awaiting them. Many Issei, at retirement age, had to rebuild their lives from scratch.

Ray “Chop” Yasui, his wife, and their two young children returned to the farm in Hood River, Oregon, that his family owned. But the couple leasing the farm refused to leave for several months. When they eventually did, Chop discovered that they had stolen farm equipment and personal items, and they had neglected to care for the farm. As in other West Coast towns, businesses in Hood River posted “No Japs Allowed” signs and refused to serve returning Japanese Americans. Chop had to travel four hundred miles to Boise, Idaho, to purchase new equipment. Other local Japanese Americans had to rely on sympathetic white friends to buy their food and supplies.

Throughout the Western states, Japanese Americans returning home encountered vigilante violence and threats, especially in rural areas. This included attempted bombings, arson, shots fired at homes, telephoned death threats, and racist graffiti—all meant to terrorize them to leave. The situation was so severe in Oregon that Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes wrote to an anti-Japanese group there: “[Your] campaign of undisguised economic greed and ruthless racial persecution has shocked and outraged good Americans in every section of the nation.” 1

In Hood River, the local chapter of the American Legion organization removed the names of all Japanese American soldiers from an honor roll at the county courthouse, which listed local residents who had served in the military during the war. The action drew condemnation across the US. Even the national commander of the American Legion was critical. After several months, the American Legion chapter added back the Japanese Americans’ names.

Japanese Americans returning to urban areas faced housing challenges. Wartime migration to West Coast cities and ongoing racial discrimination resulted in a shortage of housing options for Japanese Americans. Many of them initially lived in hostels, often set up in Japanese American Christian churches and Buddhist temples. Eventually the federal government established emergency housing in army facilities and trailer parks.

Returning Japanese Americans also had difficulty finding employment because of continued anti-Japanese racism. Lacking money to start their own businesses, many took low-wage jobs as janitors, domestic servants, and caretakers. A significant number of Issei and Nisei men became gardeners, a job requiring little start-up money.

More to explore

Image

Bronzevilles

During the war, thousands of Black people, mainly from the South, migrated to California to work in war-related industries. Due to racial discrimination, their housing options were severely limited. Many moved into pre-war “Japantowns” in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and other West Coast communities. These were some of the few areas open to newly-arrived Black people, who transformed these districts into “Bronzevilles.” They often lived in buildings not meant for residences, as shown in this photo. Black entrepreneurs opened hotels, stores, restaurants, nightclubs, and other businesses. When the war ended, many Black workers were laid off from their defense industry jobs. After the government allowed Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast, some were able to re-open their former businesses because white landlords preferred renting to them instead of Black tenants. As more Japanese Americans returned, “Bronzevilles” became “Japantowns” again, and Black residents moved to other areas.

Midwestern and Eastern Transplants

Prior to the WRA’s decision to close the camps, thousands of Japanese Americans had already been released and moved to cities outside the West Coast exclusion zone. It was natural for members of their families to join them after the WRA camps closed. Significant numbers of Japanese Americans moved to Chicago, Denver, New York, and Salt Lake City after leaving the camps.

Although their son Ray “Chop” Yasui returned to farm in Hood River, Masuo and Shidzuyo Yasui never lived there again. After the war, they settled with one of their sons in Portland, Oregon. Many other members of the Yasui family had moved to Denver, Colorado, during the war. Minoru “Min” Yasui, who had lost his Supreme Court case challenging the military’s curfew for Japanese Americans, eventually joined them. He had spent almost a year in jail for intentionally violating the curfew in 1942. The government then transferred him to the camp in Minidoka, Idaho, where his uncle and aunt were incarcerated. After his release, he reunited with his family in Denver and settled there.

The Long Struggle of Renunciants

More than five thousand Nisei who had renounced their citizenship at Tule Lake faced deportation to Japan, but the majority of them sought to remain in the United States and regain their citizenship. In November 1945, attorney Wayne Collins won a court order preventing the government from deporting many of them.

Collins also asked the court to cancel all the renunciations. He prepared individual affidavits for thousands of Nisei, explaining why they relinquished their citizenship. If the government could not contradict their statements, their citizenship would be restored. Most of the renunciants regained their citizenship by 1959, but several hundred had to wait nearly a decade longer before securing their citizenship.

More to explore

More to explore

Excerpt

Regaining Citizenship

In this essay, Hiroshi Kashiwagi describes how attorney Wayne Collins painstakingly helped to secure the U.S. citizenship of thousands of Nisei, like Kashiwagi, who had renounced their citizenship under duress at the Tule Lake camp. Kashiwagi also recounts the circumstances of his renunciation and why he reacted negatively to the “loyalty questionnaire.”

Assimilating and Forgetting

During the two decades following World War II, discrimination against Japanese Americans slowly eased in housing and employment. Publicity about the heroism of Nisei soldiers in Europe during the war helped, as did the dramatic change in the United States’ relationship with Japan, which shifted from World War II enemy to Cold War ally.

In 1952, Congress passed legislation allowing Issei to become US citizens. Japanese immigrants, most of whom had lived in America for most of their lives, could finally naturalize.

Image 45.05.04 — Thousands of Issei became US citizens after the federal government, in 1952, allowed them to naturalize. Masuo Yasui taught classes for other Issei, like those pictured here in a Portland “Americanization” school, so that they could obtain the English-language skills and knowledge of American history and government necessary to pass their citizenship tests.

Courtesy of Yasui Family Collection. Metadata ↗

After leaving the camps, most Nisei did not discuss the war years even within their families. Many of their children grew up not knowing that the US government had imprisoned their parents and grandparents.

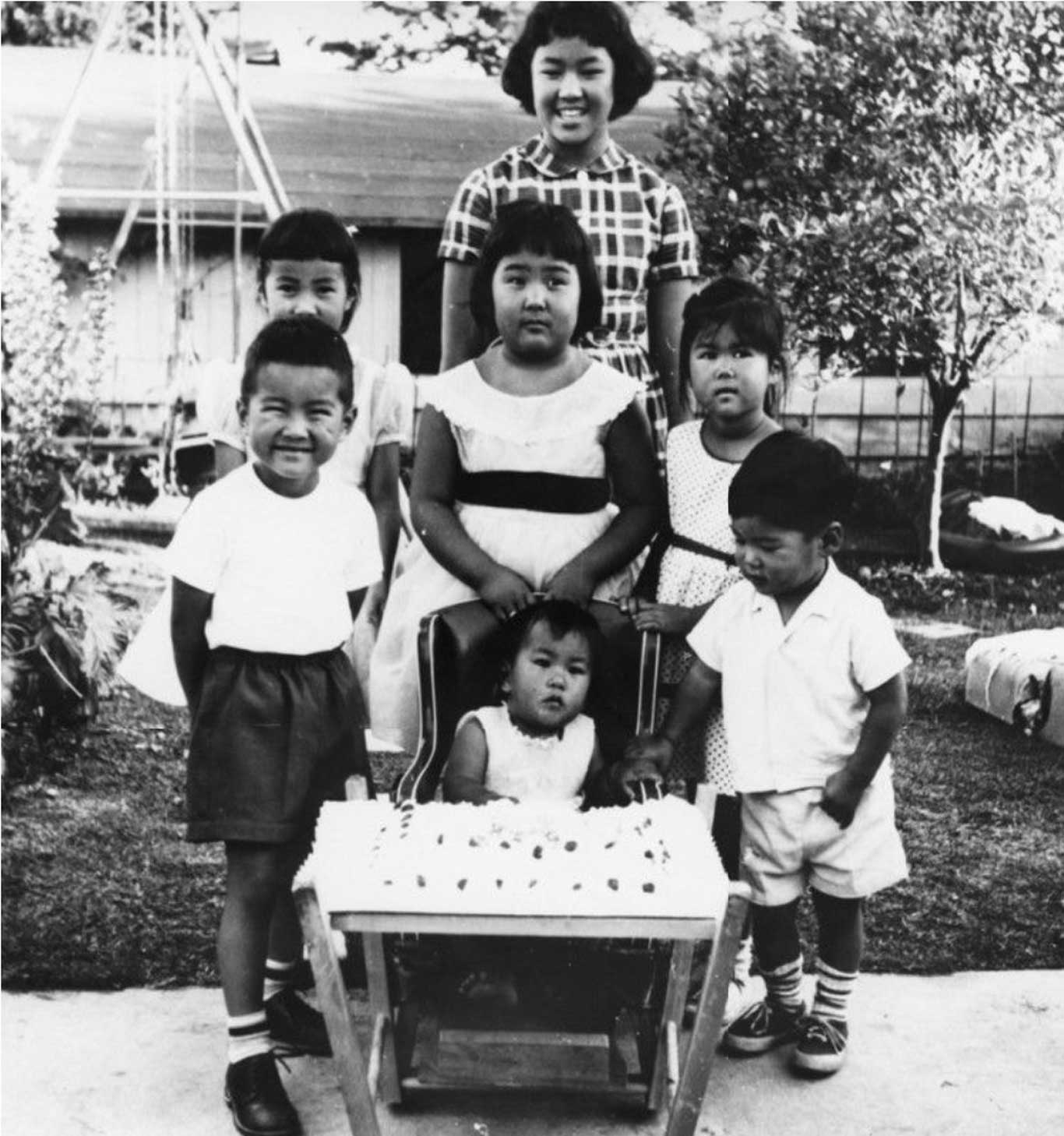

During the 1950s and 1960s, former Japanese American inmates focused on recovering from the turmoil of World War II. Many moved to white suburbs and attempted to conform to American post-war, middle-class expectations of respectability. Members of the Yasui family fit that mold. They could boast of two medical doctors, an attorney, a public health nurse, an elementary school teacher, and a successful farmer among the Nisei siblings in the family. All of them married and raised families.

Beginning in the mid-1950s and continuing into the 1960s, scholars and commentators began publishing articles arguing that Japanese Americans, who years earlier had been the targets of nearly universal public hatred in the United States, were now a “model minority,” surpassing every other ethnic group in educational, professional, and health achievements. These articles appeared during an era when African Americans were organizing for civil rights and against racist policies. Activists and communities refuted the anti-Black stereotype that Black people rely on government assistance due to “laziness” rather than institutional racism. Conservative politicians, however, seized on the “model minority” stereotype to compare Japanese American “success” with Black peoples’ purported lack of initiative. This comparison distracted public attention from the key causes of poverty in Black communities due to centuries of systemic racism, from enslavement to policies denying Black people access to quality housing, jobs, and education.

Image 45.05.05 — Many Nisei strove to assimilate and to provide their Sansei (third-generation Japanese Americans) children, like those pictured in this 1956 photo, opportunities to succeed in American society. Many Sansei grew up unaware that the U.S. government had imprisoned their parents and grandparents.

Courtesy of LAPL, Shades of L.A. Photo Collection. Metadata ↗

The “model minority” stereotype also masked problems within Japanese American communities, like broken families, drug addiction, and school dropouts among youth who rebelled against pressure to assimilate and succeed. Decades passed before Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II acknowledged that their imprisonment had deep and lasting negative impacts on them and their families, including their children who were born after the war.

Glossary terms in this module

renunciation Where it’s used

For this module, renunciation refers to people who choose to give up their US citizenship. More than five thousand Japanese Americans renounced their citizenship at one of the incarceration sites, Tule Lake. The decision to give up citizenship was complicated. Prisoners had many different reasons for doing so, including mistrust of the US government, political activism, pressure from other prisoners, and fear of returning to their former homes.

Endnotes

1 Lauren Kessler, Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family (New York: Random House, 1993), 238.