Module 6: Redress and Solidarity

How can an entire racial group be unjustly incarcerated in a democracy?

In this module, you will discover how Japanese Americans built a multiracial movement to secure an apology and monetary redress from the United States government. You will also learn about Japanese Americans’ contemporary support of other groups suffering from current and historical government policies based on race, religious beliefs, and immigration status.

What were the various strategies to win redress and reparations?

What lessons can we learn from those strategies?

How have Japanese Americans allied with other groups targeted during a time of crisis or unrest?

The Long Silence

Many Nisei whom the government had imprisoned during World War II did not tell their Sansei (third-generation Japanese American) children about their incarceration. If Nisei mentioned spending time in “camps,” they did not explain that these were prison camps, not summer camps. Consequently, many Sansei did not learn until high school or college that the federal government had imprisoned their parents and grandparents.

When they came of age and participated in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements from the 1950s to the 1970s, many Sansei asked their elders about what they experienced during World War II. But most Nisei offered evasive or vague responses often focused on the superficial aspects of camp life, rather than the violations of their constitutional rights. For most Nisei and Issei, revisiting the forced uprooting from their homes was too emotionally painful.

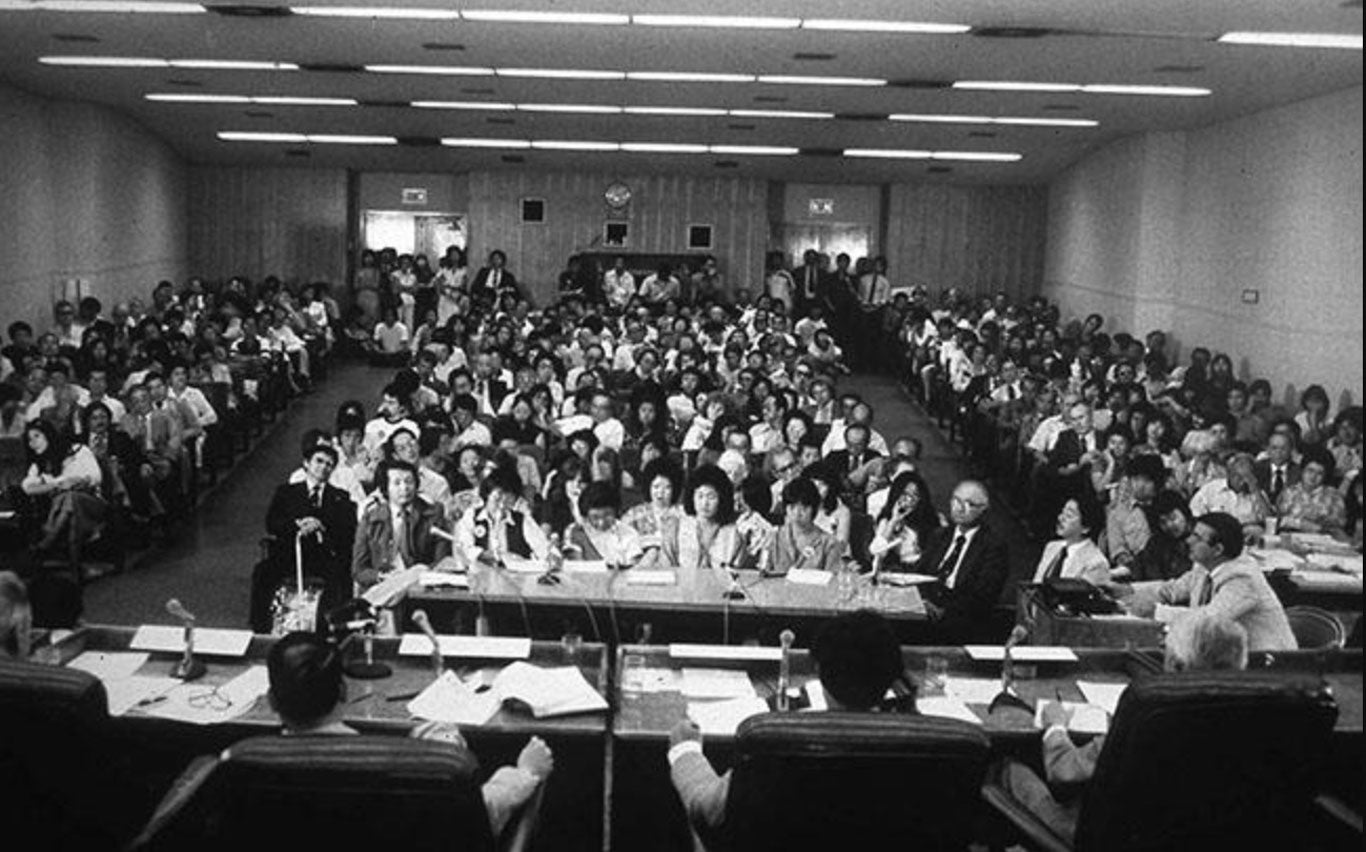

Image 45.06.01 — Inspired by the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s and protests against the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s, many Sansei became politically active, like these young Japanese Americans in 1972 opposing US militarism.

Courtesy of Mary Uyematsu Kao, 2020. Metadata ↗

More to explore

Video

02:54

The Long-term Impact of Incarceration

Growing up during the 1950s and 1960s, Lise Yasui considered her Japanese American heritage as different and unfamiliar. She and her siblings were the only mixed-race children in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, and she knew little about her father’s side of the family. When she was fifteen, Lise learned about the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans, not from her father, Shu Yasui, but in school. She asked her father about his family’s experiences during World War II. He reluctantly told her about his decision to leave the University of Oregon for Denver; the FBI arresting his father, Masuo, in Hood River; the government forcing his mother and three of his siblings into camps; and his brother Min’s court case challenging the discriminatory curfew orders imposed on Japanese Americans. In this clip (45:59 – 48:53) from her film, Family Gathering, Lise Yasui learns from her father and aunt a big secret about her grandfather and the lingering impact of false accusations of disloyalty hurled at him.

Righting a Wrong

In 1970, Nisei activist Edison Uno advocated at the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) national convention that Japanese Americans demand reparations from the US government for their unjust imprisonment. But the prospect of receiving monetary redress seemed like a pipe dream at the time. Few Japanese Americans talked openly about their wartime incarceration, even within their families. Public knowledge about the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans was virtually non-existent. Nevertheless, support for reparations grew over many years, first within the Japanese American community and then among allies.

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s had raised national awareness of government-enforced anti-Black racism. The Black Power movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s inspired young Asian Americans to develop pride in their ethnic heritage. Both movements set contexts for Japanese Americans to demand that the government acknowledge and take responsibility for its racist policies targeting them during World War II.

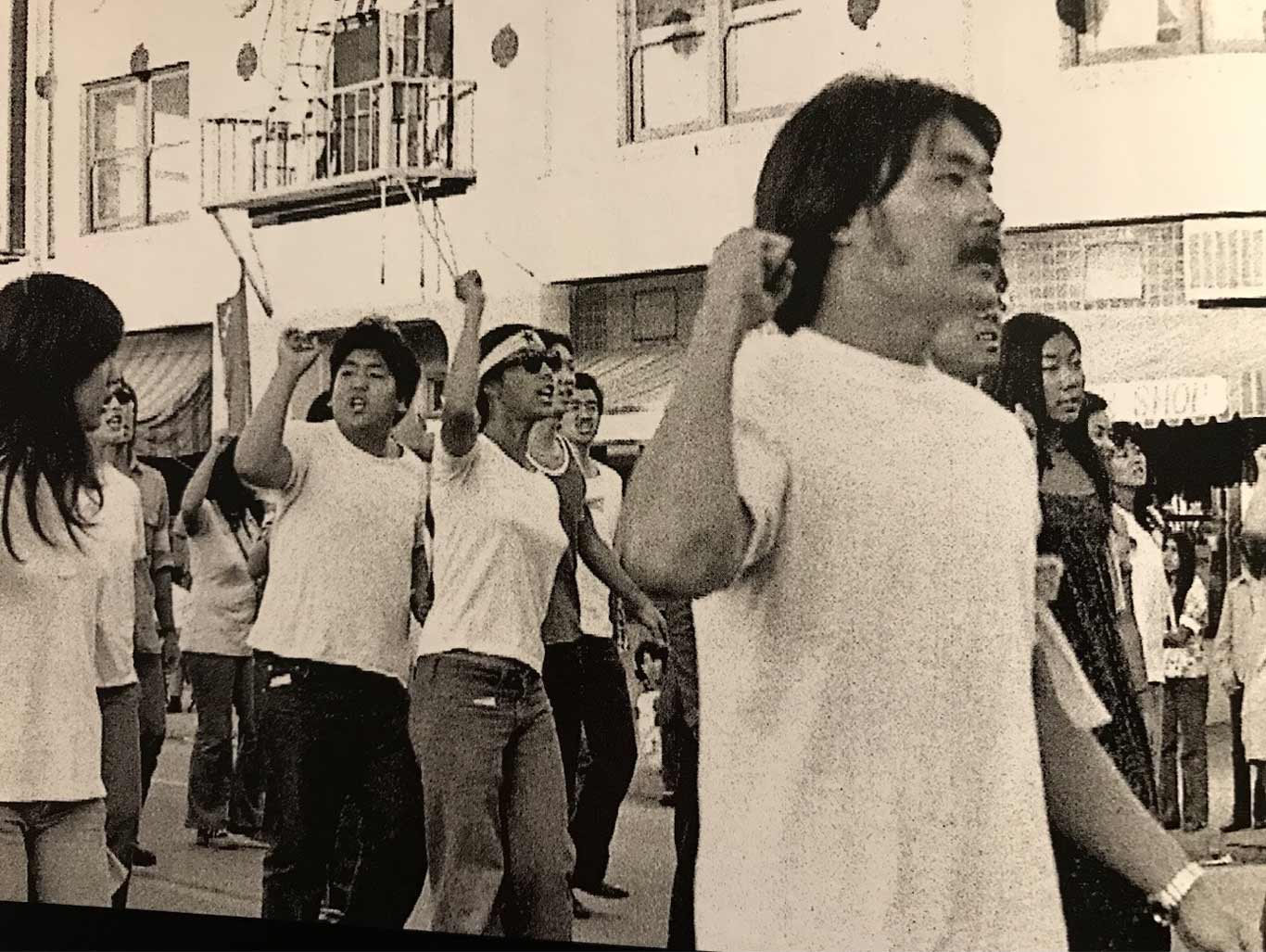

In the late 1970s, the JACL, following the advice of Japanese American members of Congress, lobbied for a federal commission to study the causes and consequences of the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, and to recommend remedies. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter approved legislation creating that body, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which held hearings in ten cities.

More to explore

Video

04:29

Giving Testimony

In 1981, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians held hearings in ten cities across the United States and heard testimony from more than 750 people. This video includes clips of nine Japanese Americans who testified at the Los Angeles hearings. They describe family separation, the poor conditions of the camps, female sterilization without consent, killing by camp guards, and the long-term trauma experienced by Japanese Americans who were incarcerated.

A grassroots group of activists formed the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR) and ensured that former inmates, not just those considered community leaders, would testify before the commission. It was challenging to convince people to testify, because most Nisei and Issei found it too painful to speak, even privately, about the war years. But many did testify, and their testimonies were cathartic—for those who shared their memories and emotions, as well as for the larger Japanese American community.

In 1982, the federal commission issued a report titled Personal Justice Denied, concluding that the wartime incarceration was the result not of “military necessity,” as the government argued at the time, but of racism, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership. The commission recommended monetary reparations and a formal government apology to all Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated.

The commission’s recommendations had to be translated into law to take effect. Over nearly a decade, hundreds of Japanese Americans and their allies of all races educated members of Congress about the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans and advocated with federal legislators to support redress. Min Yasui quit his job with the Denver Commission on Human Relations and devoted himself to speaking around the country about the redress campaign.

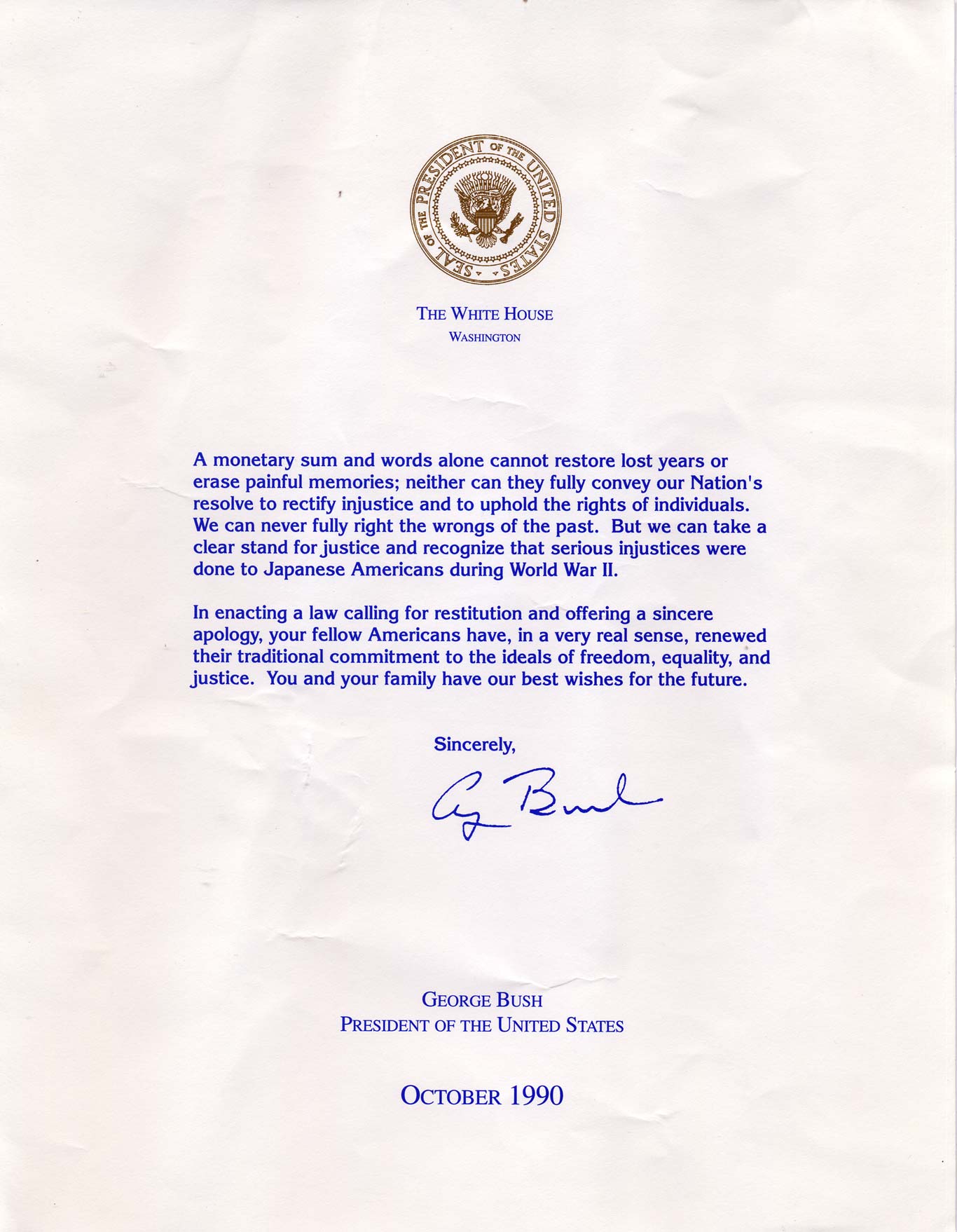

Finally on August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan approved the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, authorizing a formal government apology to Japanese Americans who had been wrongfully incarcerated during World War II, and payments of twenty thousand dollars to each survivor.

Image 45.06.04 — Japanese Americans who had been wrongfully imprisoned during World War II received this formal apology from the US government.

Courtesy of Densho. Metadata ↗

At the same time that JACL, NCRR, and others sought a legislative route to redress, another group, the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), pursued a judicial remedy by filing a class action lawsuit on behalf of Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated during World War II. A federal court dismissed the lawsuit, and the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal, ending the case. NCJAR’s efforts nevertheless raised awareness among the general public about the constitutional violations and property losses that Japanese Americans suffered during the war.

Reopening Cases

As the redress movement was gaining momentum, Min Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Fred Korematsu challenged their wartime criminal convictions. Their original convictions took place nearly forty years earlier, for violating curfew and mass exclusion orders imposed on Japanese Americans. They based their lawsuits on recently discovered official documents proving that, during World War II, government attorneys had intentionally suppressed evidence of Japanese American loyalty to the US. They also misled the Supreme Court into believing there was a military need to impose a curfew on Japanese Americans and to force them from their West Coast homes.

In the 1980s, federal judges overturned the criminal convictions of all three men.

Image 45.06.05 — Forty years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Gordon Hirabayashi, Min Yasui, and Fred Korematsu, pictured here, federal judges in the 1980s overturned their criminal convictions. All three men subsequently received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor for civilians in the United States.

Image courtesy of the family of Fred T. Korematsu. Metadata ↗

More to explore

Image

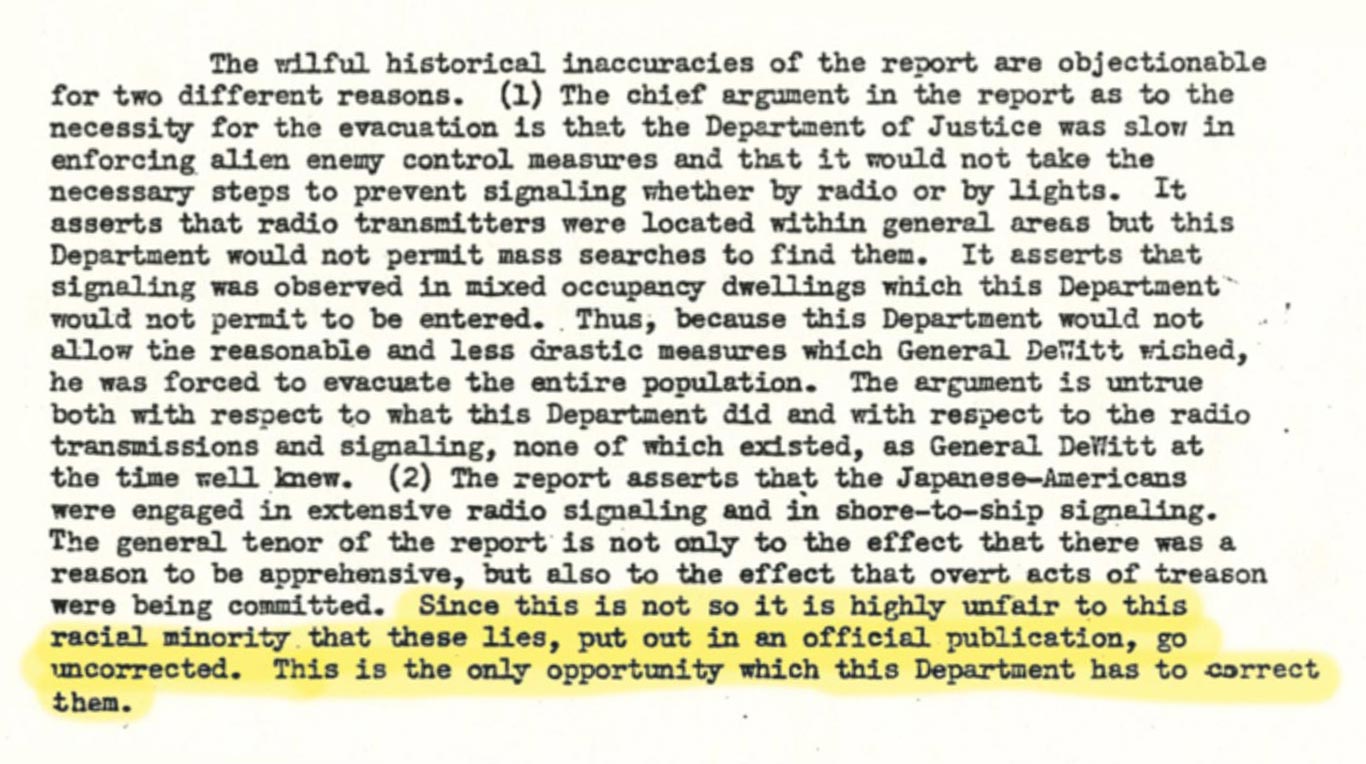

Evidence of Governmental Lies

In this 1944 memo, a Justice Department attorney complains that the government is lying to the US Supreme Court by perpetuating false claims from the general who ordered the mass removal of Japanese Americans. This and other documents proving government wrongdoing enabled Min Yasui, Fred Korematsu, and Gordon Hirabayashi to challenge their criminal convictions.

Redress for Japanese Latin Americans

As part of a coordinated strategy under the guise of Western Hemisphere security, thirteen Latin American countries deported more than two thousand Japanese Latin Americans during World War II and sent them to the United States, where the government incarcerated them in WRA camps. The US government then exchanged some of these Japanese Latin Americans for Americans held captive in Asia by the Japanese.

After the war, US officials deported more than nine hundred Japanese Latin Americans remaining in the United States to a war-devastated Japan. Several hundred stayed and eventually obtained US citizenship. They were largely excluded from the government apology and monetary payments authorized by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

Japanese Latin Americans filed a lawsuit in 1996 to obtain reparations. To resolve the litigation, the US government agreed to apologize to Japanese Latin American incarcerees and provide them five thousand dollars each. Most Japanese Latin Americans accepted the settlement. But a handful did not. They filed four lawsuits and pursued federal legislation to obtain redress equivalent to the twenty thousand dollars that Japanese Americans received. All of those efforts were unsuccessful, but advocacy groups today continue to call for the government to recognize and compensate the detained Japanese Latin Americans.

Image 45.06.06 — Members of Campaign for Justice, a group formed in 1996 to advocate for redress for Japanese Latin Americans who were deported from their countries during World War II and interned in the United States.

Courtesy of Desnho, B. Shibayama Family Collection. Metadata ↗

Remembering Incarceration Spurs Solidarity

Many Japanese Americans today educate people about the importance of civil liberties, especially for groups targeted during times of crisis.

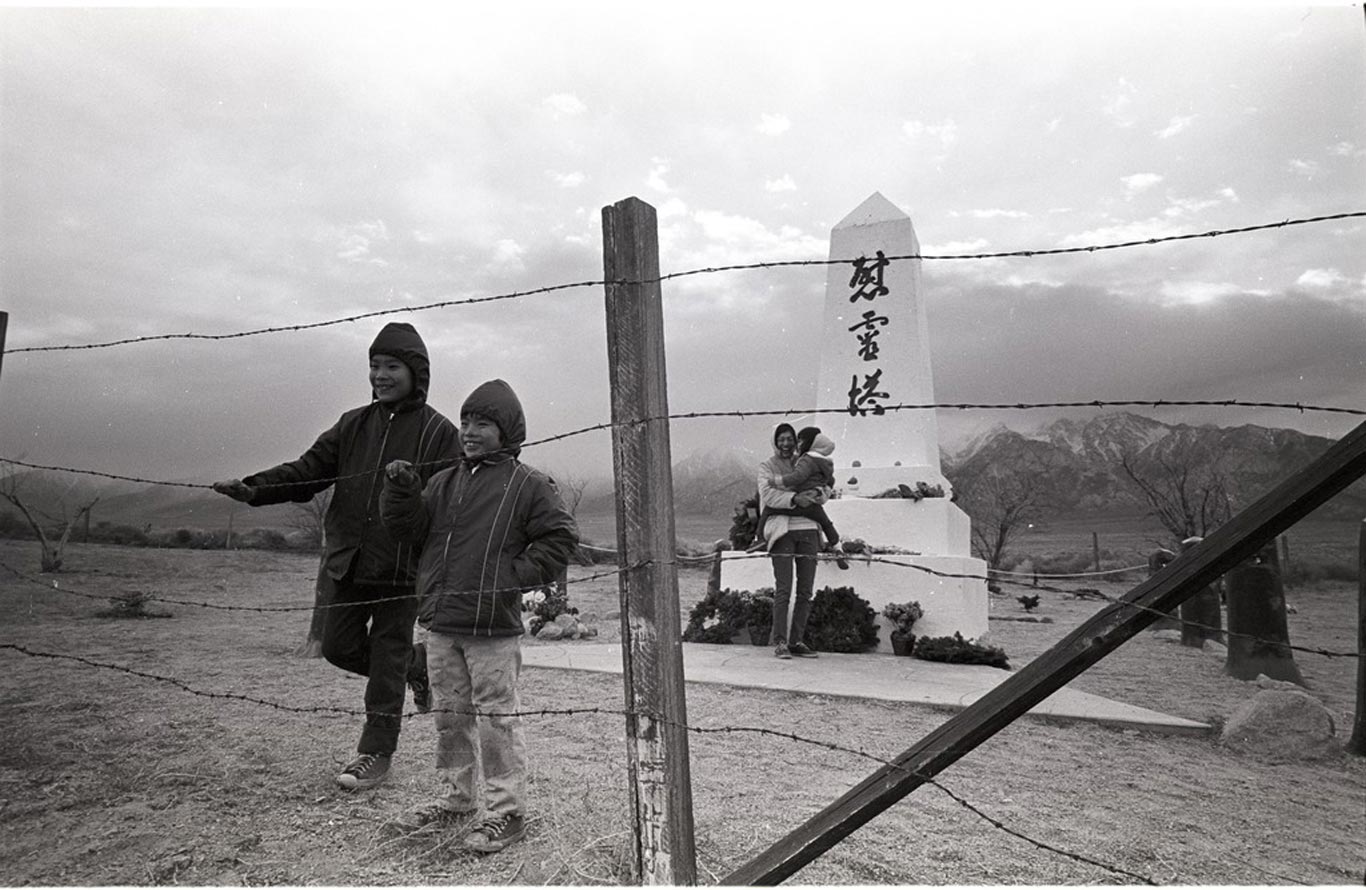

Image 45.06.07 — To ensure that the history of World War II incarceration is not forgotten, Japanese Americans have organized pilgrimages to several of the former camps sites, and they have advocated for preservation of some of the sites as educational centers. Pictured here are participants in the first pilgrimage, in 1969, to the site of the Manzanar camp.

Courtesy of Manzanar National Historic Site and Evan Johnson Collection. Metadata ↗

Image 45.06.08 — In 2017, after President Trump issued an executive order banning the arrival in the United States of people from several Muslim-majority countries, Karen Korematsu, the daughter of Fred Korematsu; Holly Yasui, the daughter of Min Yasui; and Jay Hirabayashi, the son of Gordon Hirabayashi, submitted a legal brief to the US Supreme Court in a lawsuit challenging the ban.

Courtesy of NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY, Discover Nikkei. Metadata ↗

Remembering the discrimination that they and their families experienced—and the allyship that contributed to the success of the redress movement—many Japanese Americans have connected their community’s history with the prejudice and hatred directed at other groups, including Muslims, immigrants, and asylum seekers.

Japanese Americans were some of the first to speak out in support of Muslim, Arab, and South Asian communities confronting violence, hatred, and government scrutiny after terrorists attacked the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Virginia on September 11, 2001. The JACL issued a press release on September 12, 2001, warning the government not to forfeit civil liberties and denouncing discrimination against Arab Americans and Muslims.

In 2003, Fred Korematsu submitted a “friend of the court” brief to the Supreme Court on behalf of hundreds of Muslim, Arab, and South Asian men whom the government was detaining indefinitely without charges, fair hearings, and access to lawyers.

Cross-community coalitions developed among Muslim and Japanese American organizations. Their intercommunity activities include Muslims participating in the annual pilgrimage to the site of the Manzanar concentration camp and Japanese Americans participating in community iftars, the meal Muslims eat to break the daily fast during the holy month of Ramadan.

In 2019, the Trump administration detained at a facility in Dilley, Texas, hundreds of Central American mothers and children seeking asylum. That detention center was forty miles from Crystal City, the site of a camp where the government had imprisoned Japanese and German immigrants and their families during World War II. The Crystal City camp also housed Japanese Latin Americans who had been deported from their home countries.

In response, Japanese Americans organized a protest at the Dilley detention center. Many of the protesters had been incarcerated as children at the Crystal City camp or were their descendants. They issued a nation-wide call among Japanese American civil rights and community groups to fold ten thousand origami cranes to be hung on the fences surrounding the Dilley facility. By the time of the protest, they received thirty thousand origami cranes from around the country. The individuals who organized the protest called their group Tsuru for Solidarity, as “tsuru” means “crane” in Japanese.

More to explore

Video

05:57

Protesting Contemporary Detention Centers

Soon after the Dilley protest, the Trump administration announced plans to indefinitely imprison hundreds of immigrant children at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. That locale had a bitter history for Japanese Americans, because the United States imprisoned seven hundred Issei men there during World War II. A guard shot one of them dead. Tsuru for Solidarity organized a protest at Fort Sill featuring five Japanese American elders who had been incarcerated in US concentration camps during World War II. One week after the protest, the Trump administration announced that it would not detain migrant children at Fort Sill. This video documents the protest.

Many Japanese Americans acknowledge that the redress movement would not have been successful without the support of Black political leaders and the civil rights groundwork laid, at great sacrifice, by Black activists. Since Japanese Americans are the only ethnic group to receive an apology and reparations from the federal government, some Japanese Americans believe they have a moral imperative to support reparations to Black people for slavery. Japanese Americans have been at the forefront of supporting House Resolution 40 (H.R. 40) to establish a federal commission, like the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, to study slavery and discrimination against African Americans, and to make recommendations for remedies.

Informed by knowledge of their families’ and community’s history, Japanese Americans continue to speak out for the rights of people that the US government targets because of their religious beliefs, ethnic backgrounds, or immigration status. In doing so, they are demonstrating the kind of support they wished their families had received during World War II. From within the Japanese American community and beyond, a multiracial coalition of Americans is carrying on the legacy of activism in the fight for justice, redress, and reparations.

Glossary terms in this module

Civil Liberties Act of 1988 Where it’s used

A federal law that granted all surviving Japanese American citizens and legal residents who were wrongfully incarcerated during World War II twenty thousand dollars each and a formal presidential apology. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed as a result of the findings in the federal report Personal Justice Denied and the activism of Japanese American groups, including NCJAR and NCRR.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians Where it’s used

A nine-member bipartisan group appointed by Congress to study the effects of Executive Order 9066 and World War II incarceration.

National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR) Where it’s used

A group formed in 1980 by Japanese American community activists. Influenced by the 1960s civil rights movements, the NCRR called for financial reparations and support to those suffering as a result of wartime incarceration. They also ensured that former incarcerees of all backgrounds testified before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), not just community elites and leaders.

National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR) Where it’s used

A group that formed in 1979 to gain financial reparations for Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II. They advocated for a redress bill in Congress, and after it did not pass, the NCJAR filed a $27 billion class action lawsuit in 1983 against the US government, for injuries suffered as a result of Japanese American incarceration.

Personal Justice Denied Where it’s used

The title of the 467-page report issued by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The report concluded that the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans was not a military necessity, but instead resulted from racism, wartime hysteria, and failed political leadership.

redress movement Where it’s used

The term “redress” means to right a wrong or injustice, often through compensation. During the redress movement, many activist groups fought to gain reparations for Japanese Americans who were wrongfully incarcerated during World War II. These activists sought the restoration of Japanese Americans’ civil rights, compensation for lost property, and a formal national apology.

reparations Where it’s used

The actions that a government or individuals take to offer an apology or give satisfaction for a wrong or injury.