Module 3: The Vietnamese Refugee Exodus

Has leaving Vietnam as refugees impacted what it means to be Vietnamese American?

Vietnamese arrivals in the United States occurred much later than that of other Asian communities in the timeline of Asian immigration history. Its causes can be tied to the notion that “we are here because you were there.” 1 This idea foregrounds how US militarism in Southeast Asia led to the large-scale exodus of Vietnamese refugees from the 1970s and onward. This module provides an overview of the experiences of Vietnamese refugees, from the first group of evacuees in 1975 to subsequent major groups of refugees from 1978 through the 1990s.

We will read firsthand accounts of Vietnamese refugees who left at different time periods and by a variety of means, including as land refugees and boat refugees. This also includes refugees who were ethnically Chinese and discriminated against by the government in Vietnam. We will learn from refugee camp experiences, drawing on examples in the United States, as well as other “first asylum” nations in Southeast Asia, where refugees typically first landed.

Additionally, the module will provide some context for the resettlement process, including the US dispersal policy that attempted to spread Vietnamese refugees across America—the United States Refugee Act of 1980, and the Orderly Departure Program. Among those who should not be overlooked are Amerasians, children born to Vietnamese mothers and American fathers, who faced discrimination under the Vietnamese government post-reunification of North and South Vietnam. The module will provide insight into Amerasian experiences, and encourage learners to think about the embodied experiences of war.

What were the conditions that led Vietnamese to flee their country?

What was life like for Vietnamese in refugee camps?

How did the United States and other asylum countries receive Vietnamese refugees?

The Second Wave: Boat People and Life in Refugee Camps

The late 1970s saw another surge of departures of Vietnamese out of their homeland. Much of these departures resulted from the new Communist regime’s policies to govern the economic, political, and agricultural life of the reunified country. Among those policies were the forced reeducation, torture, or killings of former South Vietnamese military personnel and US affiliates; seizure of land and property; and closure of businesses owned by ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs. The Communist regime also implemented new economic zones that forced citizens from urban regions to uncultivated or devastated rural areas.

The reeducation camps are often described by survivors as hard labor camps or prisons where they were sent for an indefinite time period. Some were released in a few months, while others were imprisoned for years or decades. Others perished in these camps due to their harsh conditions and food scarcity. Families of reeducation camp prisoners often found themselves closely monitored by the new regime, and the children of former South Vietnamese government officials faced discrimination in schools, with their opportunities for advancement in the new society greatly diminished.

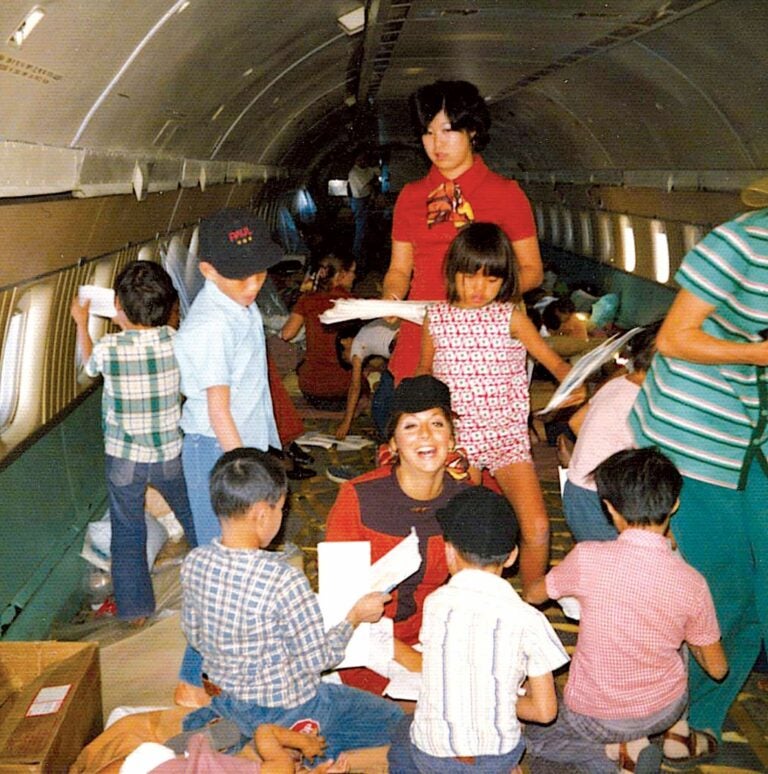

Image 19.03.04 — In the years following the Fall of Saigon, many refugees left Vietnam secretly in unseaworthy and overcrowded boats. This second wave of refugees became known as the “boat people.”

Courtesy of UC Irvine Libraries, Southeast Asian Archive. Metadata ↗

These dire political and economic conditions pushed more than two million Vietnamese people out of the country after 1975. In the years following the Fall of Saigon, many refugees left Vietnam secretly in unseaworthy and overcrowded boats. This group of refugees became known as the boat people. Most refugees fled to asylum camps in Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, or Hong Kong and awaited approval by foreign countries, namely the United States, Australia, France, and Canada. The journeys from Vietnam were often risky and dangerous, with an estimated two hundred thousand to four hundred thousand deaths at sea. Refugees who fled the country were committing what the Vietnam government considered illegal acts, and if caught, were jailed and interrogated. An underground industry of boat builders, escape organizers, and identification forgers emerged under these circumstances.

In 1978, Vietnam battled its two neighbors, Cambodia and China. These conflicts resulted in the displacement of more refugees. Further contributing to the factors in a region devastated by decades of war, the Communist regime discriminated against the largest ethnic minority population, the Chinese Vietnamese.

Many had already begun repatriating back to China after 1975, but in 1978, they were allowed to depart Vietnam aboard large vessels that could accommodate thousands at a time. Many Chinese Vietnamese left during that time under the supervision of the Vietnam government, and the mass exodus fueled negative international media coverage of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam—the new official name of the country.

More to explore

Slideshow

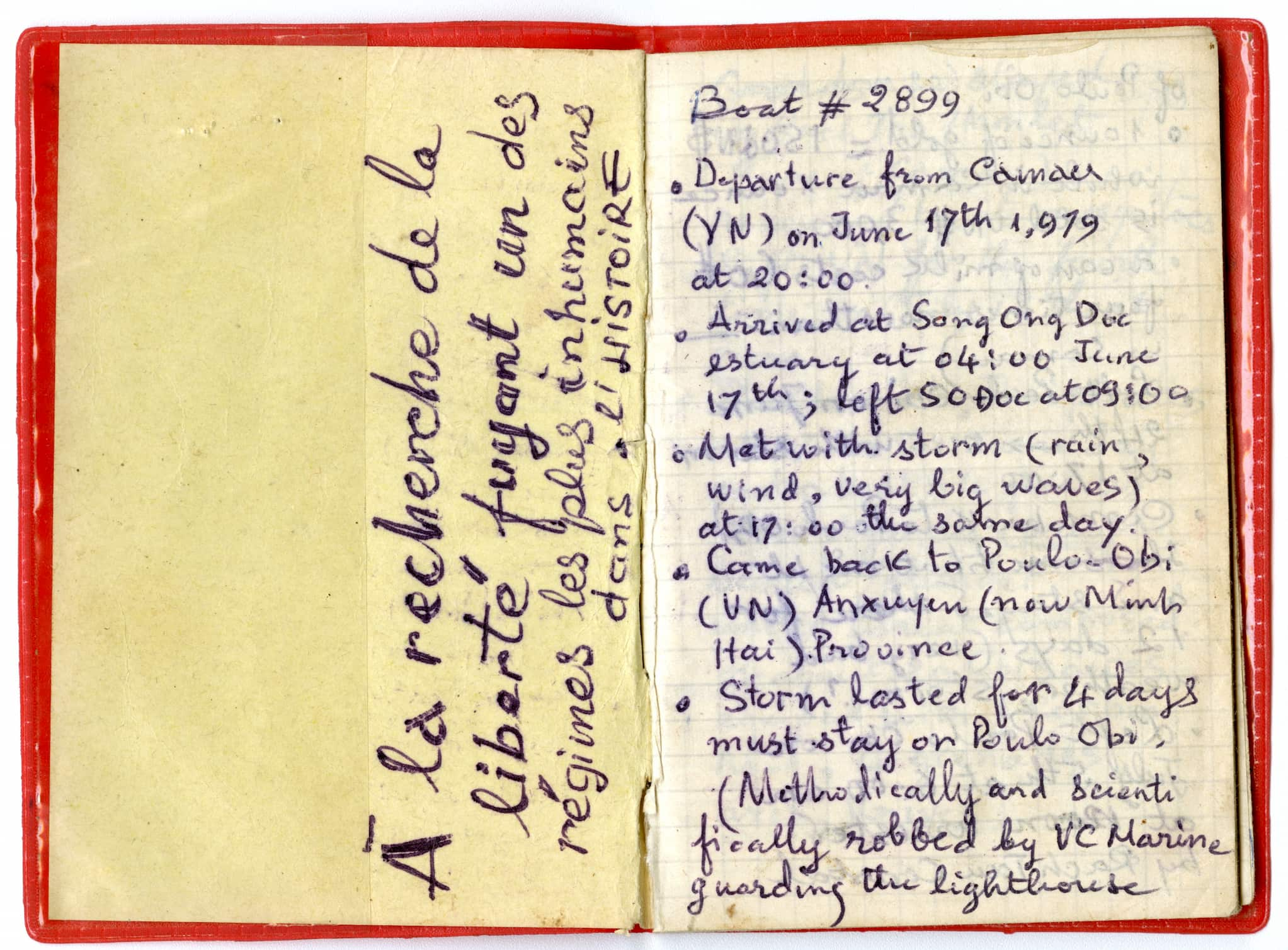

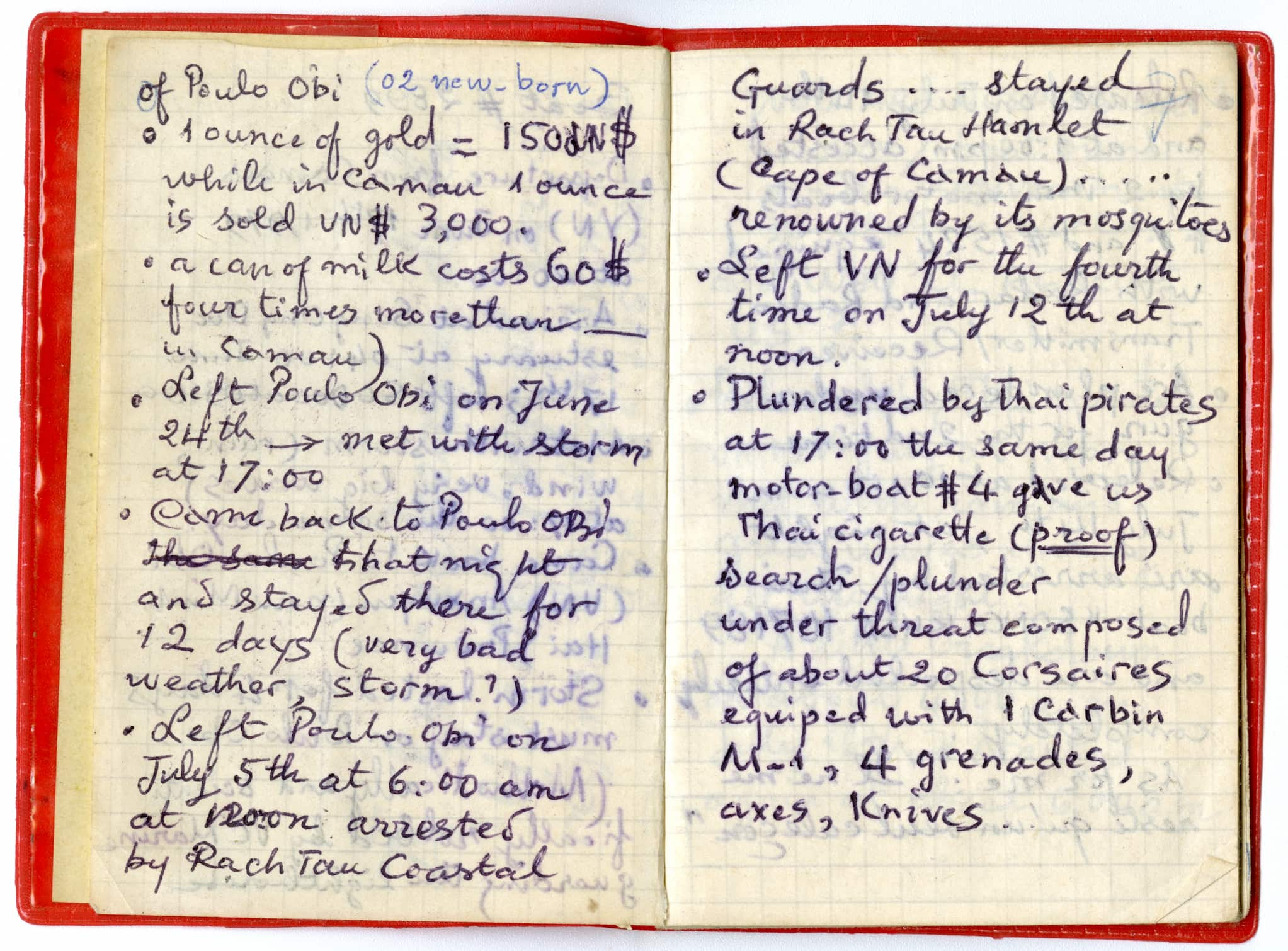

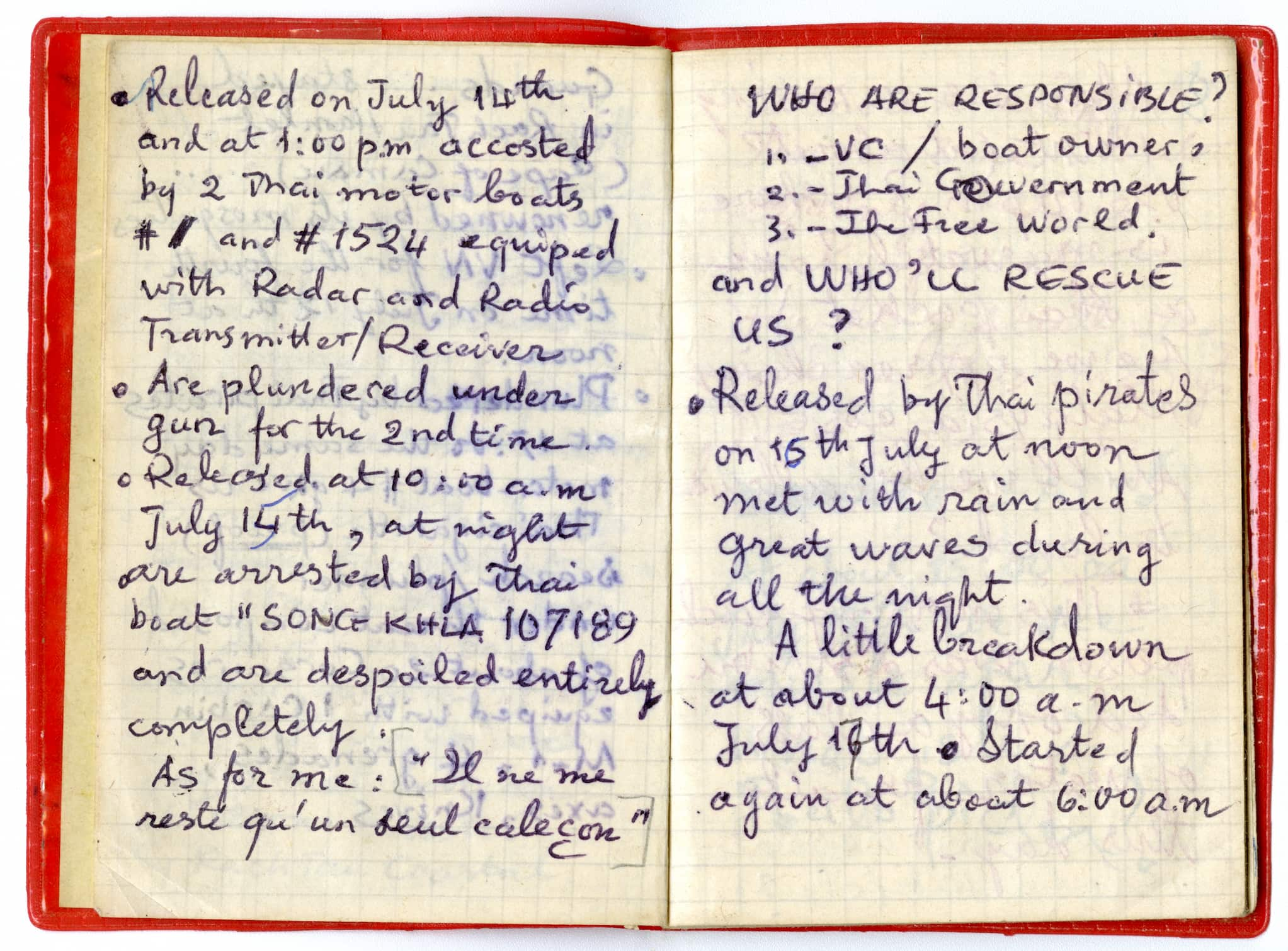

A Firsthand Account of the Boat Journey

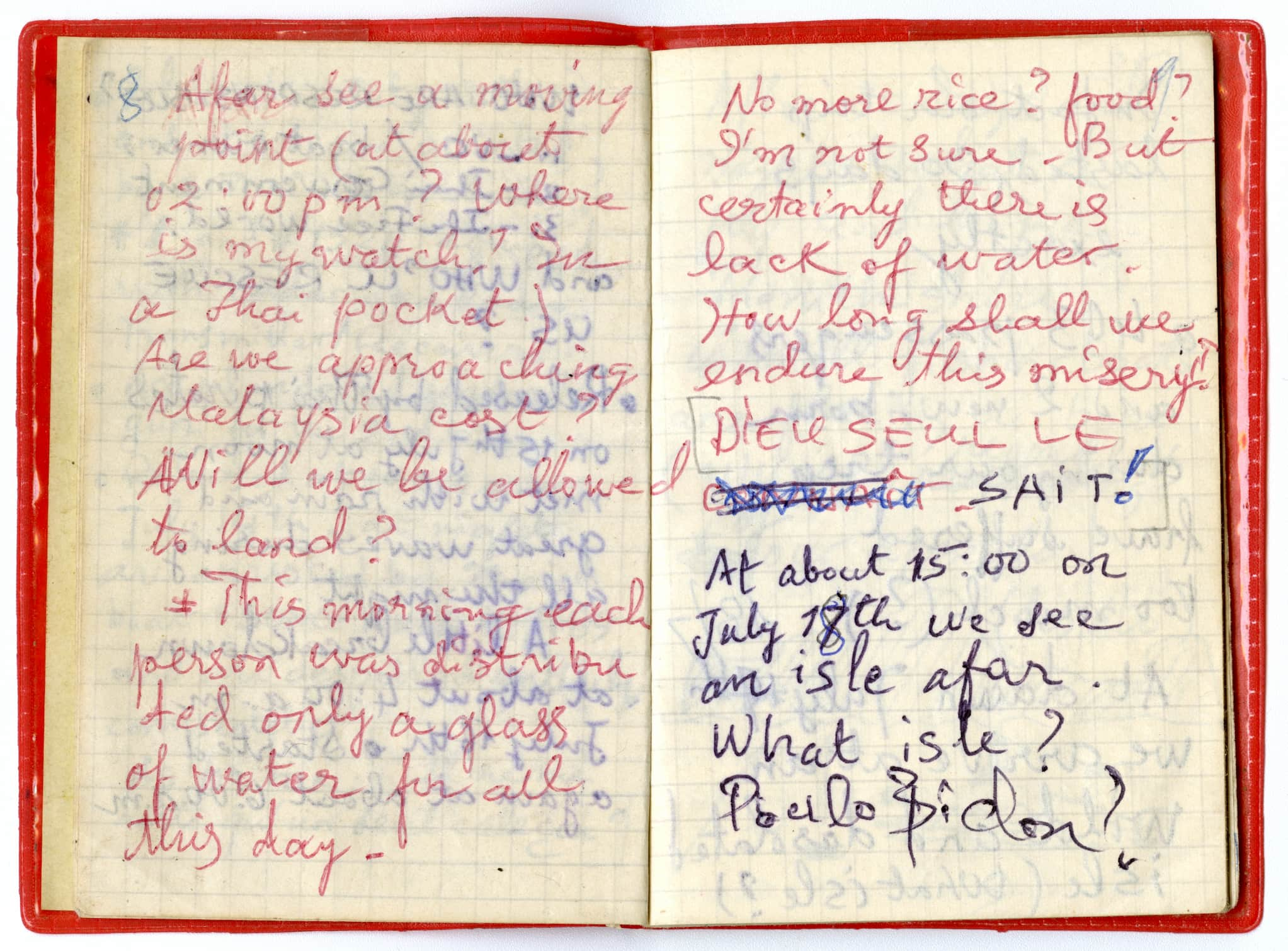

These dairy pages are excerpts from Pocket Diary of a Vietnamese Boat Person Refugee, housed at the University of California Irvine Libraries Southeast Asian Archive. The diary details an anonymous refugee’s boat journey beginning at 8:00 p.m. on June 17, 1979 from Cà Mau. This rare primary source object captures the experiences and feelings of an individual, but also sheds light on some of the first asylum countries’ roles in the refugee exodus.

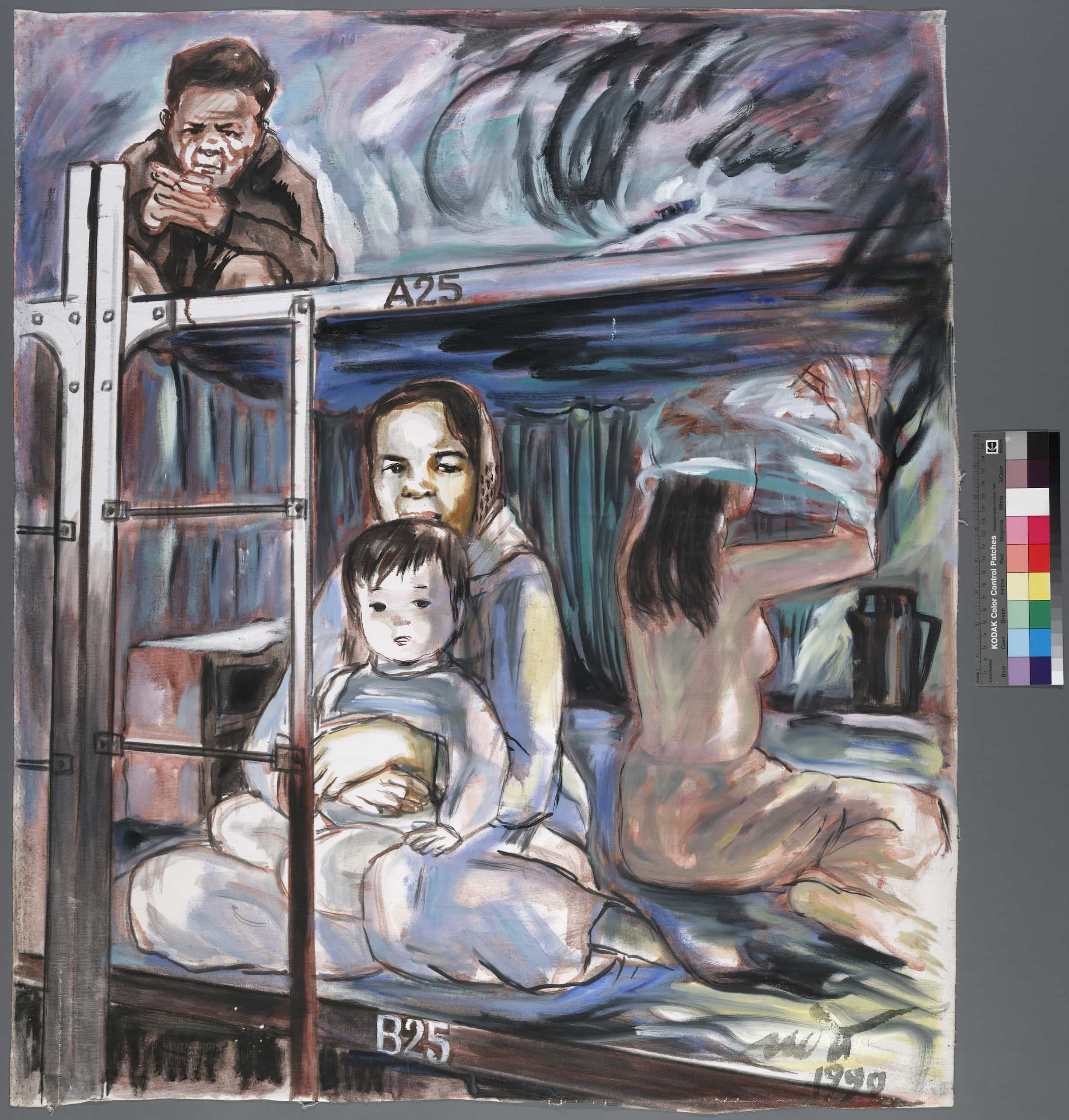

Refugees leaving in this second period spent anywhere from months to years in asylum camps awaiting admittance to a resettlement country. The camps in Southeast Asia varied between moderately comfortable quarters to enclosed, barbed-wired camps resembling prisons. Living conditions deteriorated as camps became increasingly crowded in the 1980s. Life in refugee camps was spent in line for food rations and preparing for a new life in the United States or elsewhere. Aid workers assisted refugees by facilitating socialization courses, teaching English, or helping fill out paperwork. Refugees also underwent medical examinations and rigorous interviews as part of the asylum process to determine eligibility for family reunification, sponsorship, or status as a political refugee.

Image 19.03.06 — Life in the Camp (1990) by Nguyen Dai Giang. The artwork depicts the living quarters of a refugee family.

Courtesy of UC Irvine Libraries, Southeast Asian Archive. Metadata ↗

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Việt Thanh Nguyễn explained why it is important to make the distinction between refugees’ experiences and immigrant ones:

Even at this moment in history, where the xenophobic attitudes that have always been present are reaching another peak, even people who don’t like immigrants nevertheless believe in that immigrant idea. But refugees are different. Refugees are unwanted where they come from. They’re unwanted where they go to. They’re a different legal category. They’re a different category of feeling in terms of how the refugees experience themselves. 4

The “category of feeling” may include despair, grief, debt, gratitude, resentment, hope, and persistence, among other contradictions that refugees experience. What work still remains for us to create a more inclusive world where refugees might find recognition, support, and belonging?

More to explore

Glossary terms in this module

asylum Where it’s used

The protection granted by a nation to someone who has left their established or ancestral homeland as a political refugee.

boat people (thuyền nhân Việt Nam) Where it’s used

Refugees who fled Vietnam by boat after the end of the Vietnam-American War in 1975.

diaspora Where it’s used

The dispersal, movement, migration, or scattering of a people from their established or ancestral homeland.

ethnic enclave Where it’s used

A geographical area where an ethnic group is clustered and formed into a community that is socially and economically distinct from the majority group.

Fall of Saigon Where it’s used

Refers to the collapse of the South Vietnamese capital on April 30, 1975, marking the end of the Vietnam-American War. For Vietnamese people who remained after the war, this date is often referred to as “Liberation Day.”

militarism Where it’s used

The belief in and use of force, including full-scale war, to assert power, authority, and control over a nation or people.

reeducation camp (trại cải tạo) Where it’s used

Prison or hard labor camps under the Communist government of Vietnam where approximately 200,000 to 300,000 former South Vietnam military officers, government workers, and affiliates were sent for months to years following the Vietnam-American War.

refugee Where it’s used

A person who has been forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster.

xenophobic Where it’s used

Having or showing a fear or hatred of foreigners, strangers, or people who are perceived as strange or foreign.

Endnotes

1 This aphorism is attributed to the late antiracist scholar, Ambalavaner Sivanandan (known as Siva). He was referring to postcolonial migration and used this phrase to critique imperialism.

2 Anh Do, “Vietnamese refugees began new lives in Camp Pendleton’s 1975 ‘tent city’,” Los Angeles Times, April 30, 2015, https://graphics.latimes.com/tent-city/.

3 Quynh-Trang Nguyen, interviewed by Brandon Nguyen, February 21, 2012, Viet Stories; Vietnamese American Oral History Project, University of California, Irvine Southeast Asian Archive, https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/81235/d84g2r/.

4 Viet Thanh Nguyen, “‘Call Me a Refugee, Not an Immigrant’: Viet Thanh Nguyen,” interview by Jon Wiener, The Nation, June 11, 2018, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/call-refugee-not-immigrant-viet-thanh-nguyen/.