Module 4: Building Community in “Little Saigon”

Has leaving Vietnam as refugees impacted what it means to be Vietnamese American?

Vietnamese American communities today are diverse, consisting of immigrants, refugees, as well as second and third generations born after the Vietnam-American War. Their times and contexts of arrival in the United States are important factors for understanding Vietnamese American experiences. Additional factors such as the regional, religious, gender, and class backgrounds of individuals, also shape their experiences and approaches to building community.

This module explores the development of Vietnamese American communities, many of which are known as “Little Saigon” districts, across the United States in California, Texas, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and the Virginia-Maryland-DC area. The largest population of overseas Vietnamese is in Orange County, California, with a population of over two hundred thousand.

We will take a closer look at these diasporic communities in order to understand how a group of relative newcomers to America were able to make great economic, cultural, and political impacts on a region in less than half a century. We will gain insight into the reasons for Vietnamese resettlement in Orange County, the discrimination faced by early refugees rebuilding their lives, and the opportunities they carved out through entrepreneurship and intra-ethnic networks.

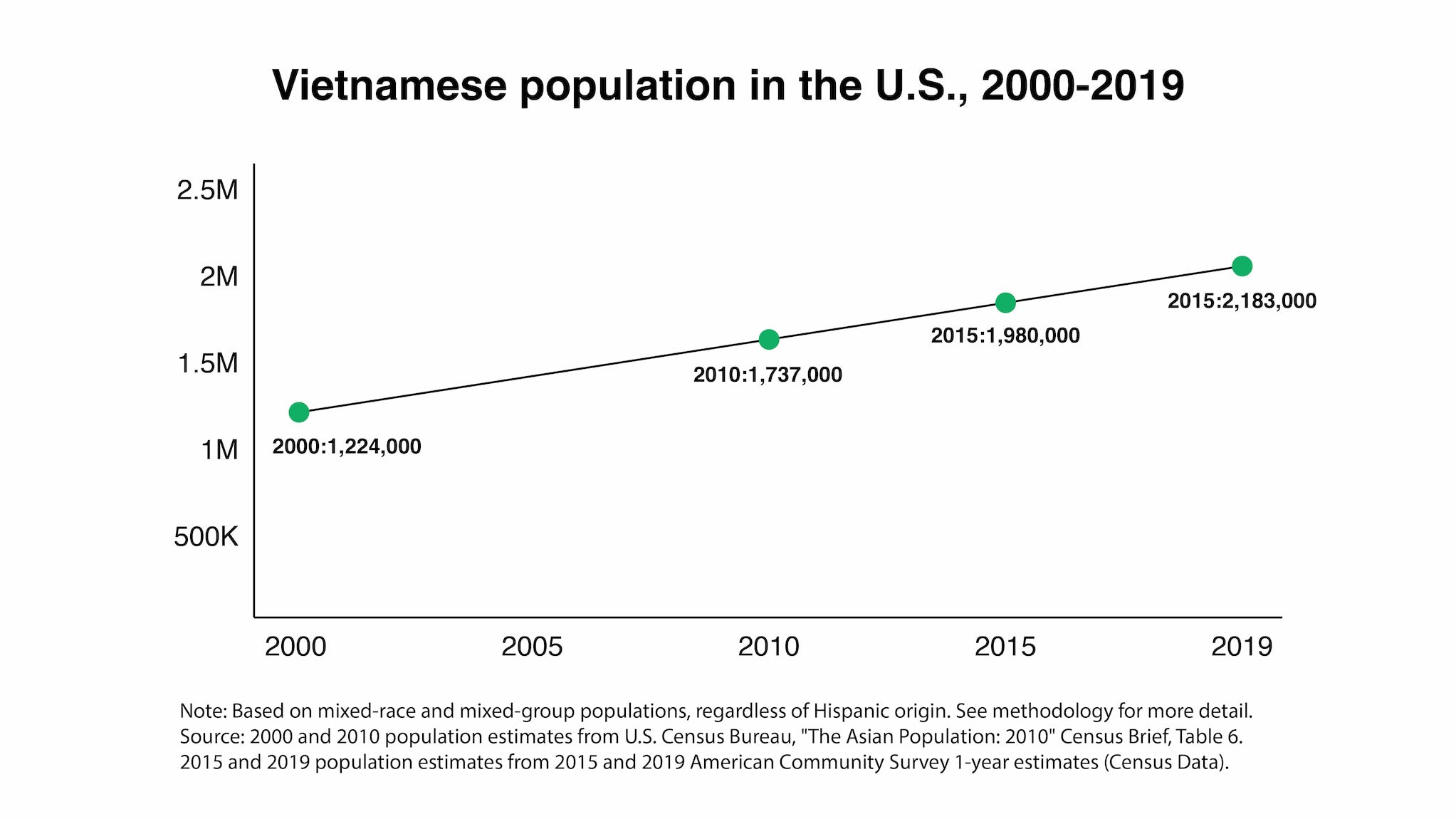

Image 19.04.01 — Vietnamese population in the US, 2000–2019 by the Pew Research Center.

Courtesy of Pew Research Center. Metadata ↗

What are the prevalent social issues facing Vietnamese American communities?

What does an ethnic community need to thrive in America?

How did Vietnamese Americans come together to form Little Saigons?

From Sài Gon to Little Saigon

Vietnamese communities have formed all across the United States since the end of the Vietnam-American War in 1975. Vietnamese people are now the fourth largest Asian American and Pacific Islander group in the United States, after Chinese, Indian, and Filipino. The largest concentration of Vietnamese Americans can be found in and around the Little Saigon district in suburban Orange County, California, in the cities of Westminster and Garden Grove. Situated in unceded ancestral lands of the Juaneño/Acjachemen and Gabrielino/Tongva Nations, the region later became Spanish and then Mexican land before white settlers claimed ownership. While Vietnamese Americans are relative newcomers to this area, they are part of Asian American history there, connected to the Chinese and Japanese Americans who built the infrastructure for Orange County through their labor on the railroads and farm fields.

The now “not-so-little” Little Saigon has helped bolster the region’s economy with tourism and business. According to 2020 Census figures, the Vietnamese American population in Southern California is close to four hundred thousand, by far the largest concentration outside of Vietnam.

Although the American government attempted to disperse refugees all over the United States, many Vietnamese people exerted agency over their lives by migrating from their first resettlement areas to be among others that shared similar histories, cultural backgrounds, and language. This process, called secondary migration, led to the formation of Little Saigon districts throughout the country.

Orange County’s Little Saigon is situated about sixty miles north of the Marine Corps base Camp Pendleton, the first of four emergency processing centers set up to receive evacuees from South Vietnam and Cambodia in April 1975. About fifty thousand Vietnamese people were processed through the makeshift “tent cities” of Camp Pendleton, and from there, many resettled in the Orange County area to work in the nearby defense and high-tech industries and in small entrepreneurial enterprises.

Southern California’s warm climate and, then-affordable housing and real estate, provided additional incentives for secondary migrations into the region. Faith-based organizations led the effort in meeting the needs of the newly arrived refugees.

Outside of Orange County, the second largest concentration of Vietnamese Americans can be found in San Jose and surrounding cities in Northern California. Like other Asian American workers, Vietnamese Americans were drawn to the area by the ascension of Silicon Valley in the latter half of the twentieth century, which provided ample job opportunities in the high-tech sector and assembly lines.

The third largest concentration of Vietnamese Americans can be found in Houston, Texas, represented by the four-mile stretch of Bellaire Boulevard. After the war, many Vietnamese settled in the Gulf Coast, with some eventually relocating to nearby Houston, drawn to the fishing industry and the warm climate. As this community grew in the late 1970s, white fisherfolk saw Vietnamese people as a threat to their businesses.

The Ku Klux Klan threatened them, but they persisted. In the early 2000s, Houston’s Vietnamese American population increase has been attributed to outmigration from California due to high home prices and cost of living. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 also displaced many Vietnamese Americans in the Louisiana region to seek out new livelihoods in Texas.

More to explore

Image + Audio

Vietnamese Resettlement and the Ku Klux Klan

As Vietnamese refugees resettled along the Gulf Coast of Texas in the 1970s and formed fishing communities, tensions escalated between Vietnamese fishermen and white fishermen. The Ku Klux Klan got involved and threatened Vietnamese people using intimidation tactics such as setting houses and boats on fire. These experiences of Vietnamese resettlement in Texas demonstrate the discrimination faced by early refugees rebuilding their lives.

In New Orleans, Louisiana, Vietnamese Americans are concentrated in the area of Versailles, where they are primarily united through their membership in the Catholic community. Vietnamese people were drawn to the region because of active recruitment by Catholic parishes, the availability of jobs in the service sector, and the fishing and shrimping industry. When Hurricane Katrina toppled communities in New Orleans East, Vietnamese Americans became much more politicized and actively reconstructed their communities through church- and youth-led efforts.

The media sometimes considers this Vietnamese community to be triply-displaced, from Vietnam to America and then by this natural disaster, yet somehow remaining fiercely resilient. However, this praise is a double-edged sword as it is often juxtaposed with comparisons to African Americans’ slower rates of rebuilding in New Orleans.

This narrative reinforces model minority stereotypes, which fuel anti-Black racism by misdirecting blame towards Black communities rather than systemic causes. In reality, natural disasters disproportionately impact communities of color more because of these systemic outcomes. Despite these divisive narratives, there have been examples of joint organizing between Vietnamese and Black communities in the wake of Katrina. These efforts provide a roadmap to learning from racial solidarity.

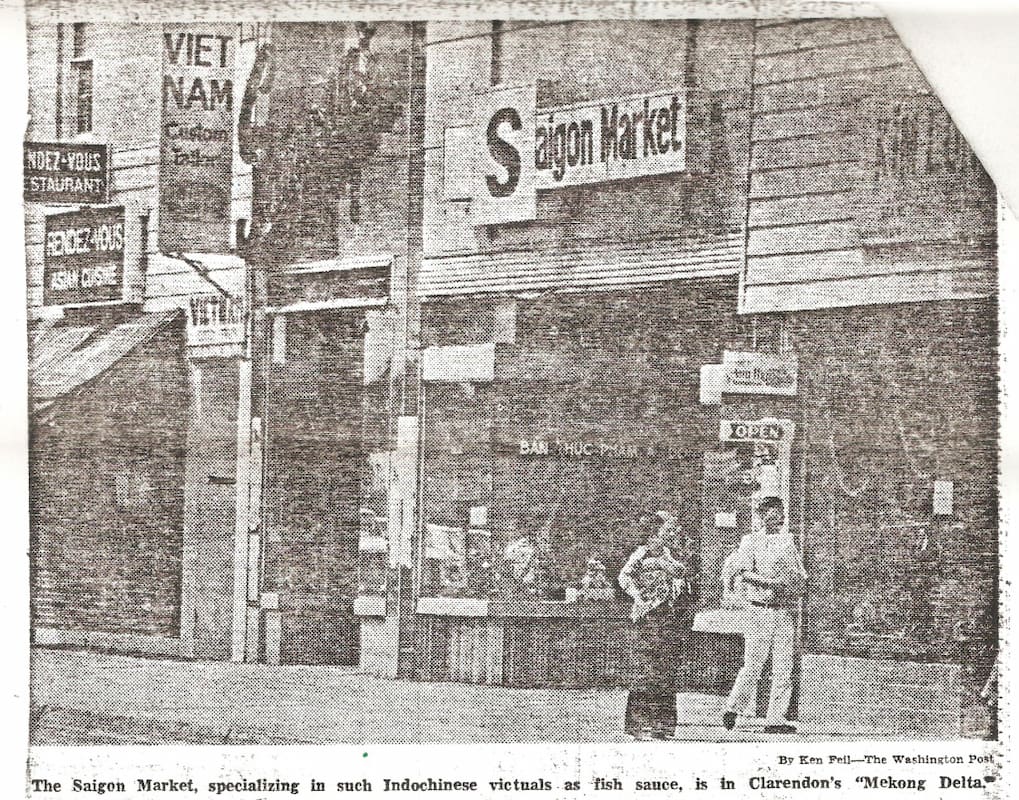

On the East Coast, Vietnamese Americans gather in areas such as Fields Corner in Boston, Massachusetts, and Eden Center in Falls Church, Virginia. When Vietnamese Americans do not lay geographical claim to a particular neighborhood or section of a city, they often integrate into other established, or pan-Asian, business districts.

This is the case for Honolulu Chinatown in Hawaiʻi, which houses many Vietnamese-owned businesses. California’s Los Angeles Chinatown has seen a transition towards a predominant Chinese-Vietnamese population in the latter half of the twentieth century, with physical evidence found in the multilingual business signs and languages spoken among residents and patrons there.

Today, Little Saigon districts offer what scholars have called “institutional completeness” for Vietnamese Americans. This means that the economic, social, linguistic, and cultural needs of the community can be met within its geographical boundaries.

Cultural and Social Hubs

As a hub for the Vietnamese diaspora, Orange County’s Little Saigon has been featured in a number of films, documentaries, fiction, and cookbooks. In 2007, Little Saigon and Vietnamese Americans were the topic of a Smithsonian traveling exhibition called “Exit Saigon, Enter Little Saigon,” which featured stories of Vietnamese Americans since 1975 through photographs and educational materials. Marking the significance of Vietnamese American placemaking efforts, a number of academic studies and popular cultural productions have raised awareness about Little Saigon to the mainstream public. Two recent novels by second-generation Vietnamese American writers are set primarily in Little Saigon: Carolyn Huynh’s The Fortunes of Jaded Women (2022) and Loan Le’s A Pho Love Story (2021).

Every year for Tết, also known as Lunar New Year, Vietnamese people from all over the country and the world come to Orange County’s Little Saigon to celebrate the most important Vietnamese holiday. Tết is a time of renewal and family connectedness, when rituals such as tending to family altars or preparing specific new year dishes help Vietnamese people who live oceans apart from their ancestral lands, renew their sense of identity.

Even when Vietnamese people were temporarily in the “first asylum” camps in Southeast Asia, they observed Tết rituals or organized collective celebrations. In Orange County’s Little Saigon district, the annual Tết Festival has been organized by Vietnamese Americans since the very beginning of the community’s formation, starting modestly among church groups in the late 1970s. In 1982, the Union of Vietnamese Student Associations (UVSA) consolidated the Tết Festival into a large event that continues to this day, attracting over one hundred thousand attendees per year.

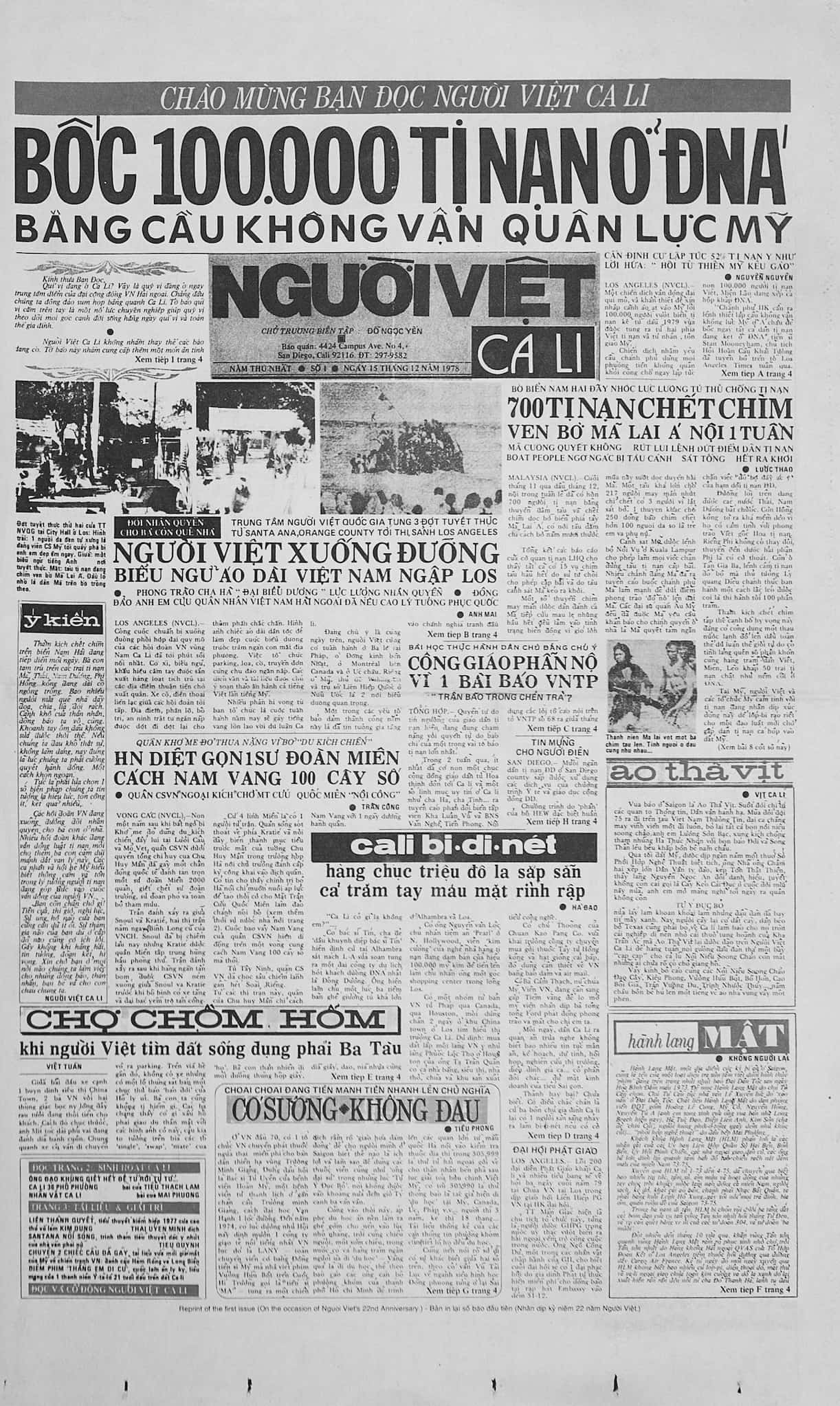

Besides providing a place for celebrations of Tết and other Vietnamese holidays and historical events, Little Saigon also serves the function of anchoring Vietnamese identity and “imagined community” through cultural representation. This happens through its extensive media networks that include the largest Vietnamese-language daily newspaper in the country, Người Việt Daily News. In 1978, Yến Ngọc Đỗ started Người Việt from his home in Garden Grove, California. The newspaper now includes multimedia outlets for sharing information in Vietnamese and reaches a global diaspora.

Radio and television are also important sites through which Vietnamese people across the United States receive their news to maintain ties and connectedness to their culture. Popular television channels include Little Saigon TV, Saigon Broadcasting Television Network (SBTN), and VietFace TV, to name a few. Radio stations include Viet Nam California Radio (VNCR), Little Saigon Radio, Radio Free Vietnam, and others.

Along with the news and information industry, Vietnamese Americans are connected through popular entertainment such as the music variety show Paris by Night from Thúy Nga Productions and programs by Asia Entertainment. These music variety shows, featuring singers of popular Vietnamese music and dance, are performed live and taped for wide circulation in the US and abroad. While the shows travel and tour widely, both companies are headquartered in Orange County’s Little Saigon.

Having cultural food, goods, and services in one area for the community is another way Little Saigon districts meet the needs of Vietnamese Americans. Restaurants are among the most popular attractions for those living in Orange County’s Little Saigon and those who visit. Language schools and tutoring centers also meet the demands of a community with a vibrant third generation that straddles identities and histories.

In the community’s early stages of development, many organizations in Little Saigon focused on social services. Now, more organizations aim to preserve and disseminate Vietnamese heritage and culture. For example, journalists and artists founded the Vietnamese American Arts and Letters Association (VAALA) in 1991 to promote art by and for the community. VAALA produces a variety of programs today, including an annual international film festival, established in 2003, to showcase films about Vietnam and the diaspora.

Entrepreneurship and Nail Work

Many new immigrants in the United States establish their own businesses to serve the specific needs of their community members while building economic opportunities for themselves. In the twenty-first century, Vietnamese Americans have come to dominate the nail salon industry and make up about 50 percent of the nail technician population in the country, and 80 percent in California.

The origin story of how Vietnamese Americans came to dominate the nail salon industry has been traced numerous times in media to the first wave of refugees who entered the US in 1975 via Camp Pendleton and then temporarily sheltered at Weimar Hope Village, a former tuberculosis quarantine center. Actress Tippi Hedren, who was doing humanitarian work at the time, was influential in providing job training resources to a group of twenty Vietnamese women at Hope Village, who then went on to open nail salons of their own. The owners of Advance Beauty College, a Vietnamese American cosmetology school, have made multiple public appearances with Hedren to acknowledge her part in this history.

By increasing access to and lowering the cost of professional nail care, Vietnamese Americans have led the way in democratizing nail services. However, related to the spread of these “bargain” nail salons are labor issues and health hazards. In the last decade, social justice activists have lobbied for legislation that would address the toxic chemicals used in nail care products and the unsafe labor conditions pervasive in nail salons.

Additionally, the story of “successful” Vietnamese Americans in nail work is further called into question when we consider the former tuberculous quarantine center that was used to temporarily house, socialize, and resettle approximately eight hundred Southeast Asian refugees from June to July of 1975.

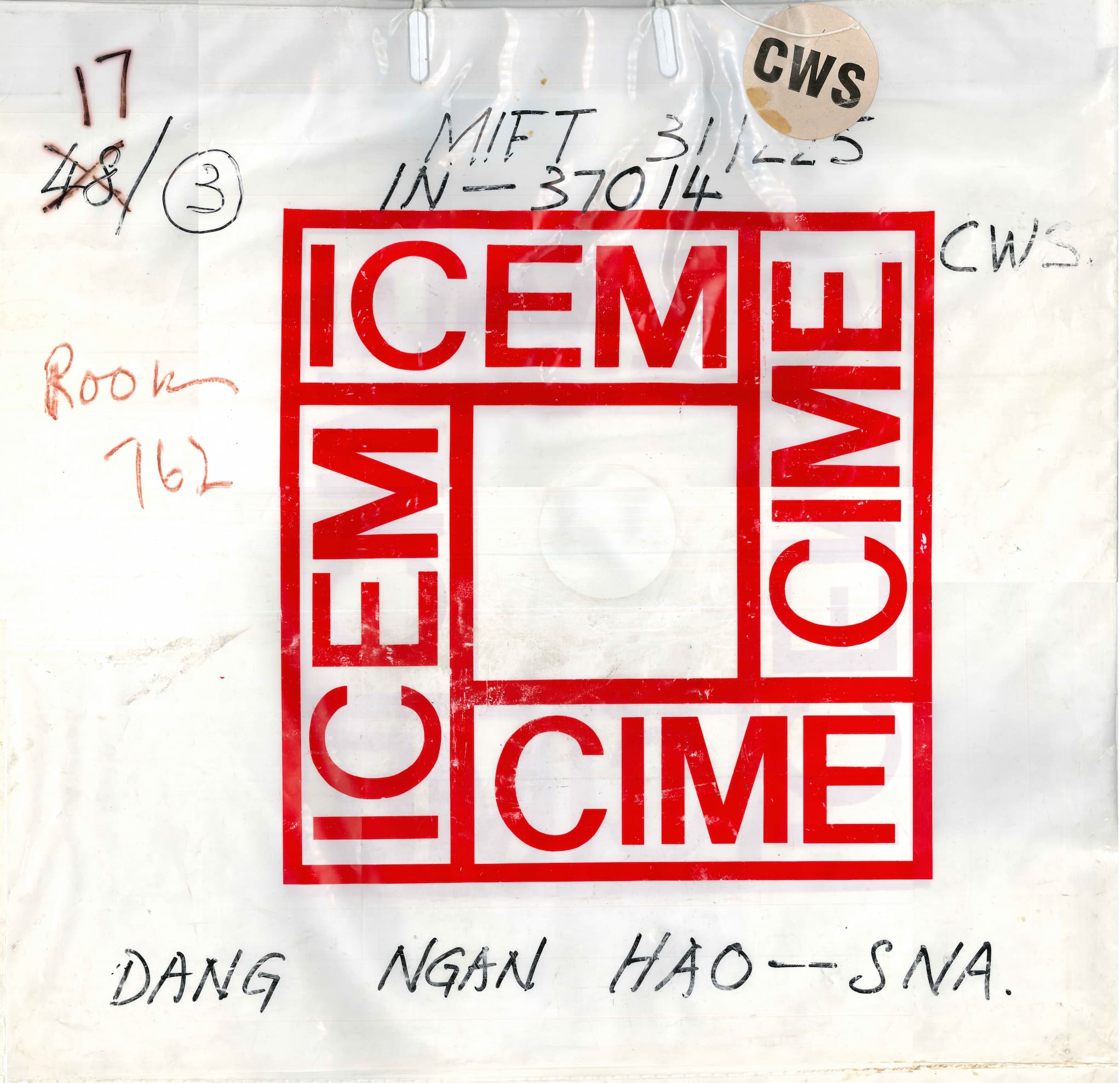

A required protocol for refugee screening involved chest X-rays and other invasive exams to rule out tuberculosis and other infectious illnesses. Refugees arriving in the US often carried along white plastic bags large enough to transport the X-rays issued by the International Committee on Migration or other similar agencies. These bags contained proof that they were medically-cleared for resettlement. From their initial medical clearance to the longer exposure to toxic chemicals and unsafe work conditions, the story of Vietnamese American nail salons must be understood as a complex history in the so-called “land of opportunity.”

Today, organizations such as the California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative (CHNSC) work to promote awareness and lobby for healthy and fair conditions for workers, who are primarily women.

In an oral history interview, Tran Wills, founder of Base Coat Nails in Denver, Colorado, observes that:

It is a beautiful industry, of people of all races, backgrounds, economic backgrounds, and everything. I think, too, people think of the beauty industry that it’s like a hobby. No—all of us have chosen this as our livelihoods and our careers … you pay money and you have professional training …The industry has been so stigmatized with this almost subservient attitude … But, the funny thing about it is, people get their nails done more than their hair or their makeup done.1

– Tran Wills

Glossary terms in this module

diaspora Where it’s used

The dispersal, movement, migration, or scattering of a people from their established or ancestral homeland.

Endnotes

1 Tran Wills, interview by Kelsey Kim, Chemical Entanglements: Oral Histories of Environmental Illness, UCLA Center for Oral History and Research, September 11, 2020, https://oralhistory.library.ucla.edu/catalog/21198-zz002kpkh2.