Module 5: Politics and Remembrance in the Vietnamese American Community

Has leaving Vietnam as refugees impacted what it means to be Vietnamese American?

Vietnamese American politics is a complex and multilayered engagement with United States politics, Cold War history, and ongoing transnational relationships with the homeland. For half a century, anti-Communism has been the dominant community politics for many Vietnamese Americans of the first and second generation, particularly those whose lives were impacted by war and displacement. This political ideology has often erupted in censorship, protest, and violence across many Vietnamese diaspora communities in the United States and around the world.

Vietnamese American anti-Communism can be understood through the frame of Cold War anti-Communism pervading much of American politics in the 1950s until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. However, this should not be our only frame of reference, as this community’s politics has been shaped by a particular refugee discourse fraught with tension and irresolution.

In this module, we explore how remembering and commemorating the past can be a complicated political process; we also discuss the different strategies used by Vietnamese Americans to navigate this complexity.

How do we commemorate the war, South Vietnam, and the dead without reproducing narratives of victimization, refugee debt, and gratefulness?

How do we respect our ancestors and pay tribute to their lives when we do not have access to their stories?

How have Vietnamese Americans supported and resisted dominant historical narratives about the Vietnam-American War?

Vietnamese American Politics

More than an ideological opposition to socialism, Vietnamese American anti-Communism must be further placed within historical context. We must understand it as a political discourse emerging from the civil war between North Vietnam and South Vietnam; the evacuation of the South’s urban elites in 1975; the exodus of refugees from the late 1970s to the late 1980s; and the reeducation camp experiences of men and women from the former Republic of Vietnam. These particular historical events frame and help to reinvigorate anti-Communism as a political and cultural movement in and outside the United States.

Historically, many Vietnamese Americans are united through an “imagined community” defined by shared anti-Communist beliefs and expressions, despite their heterogeneity in class, education, region, and religion. This conservatism and pervasive anti-Communism shows up quite visibly today in places like Orange County’s Little Saigon, home to many officers of the former Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), and immigrants sponsored via the Orderly Departure Program from 1979 to 1994, including former political prisoners who served a minimum of three years in Communist reeducation camps.

Their experiences of persecution and imprisonment during wartime by the Việt Cộng and in the postwar years by the new Socialist Republic of Vietnam, have influenced the diasporic community’s politics and its attitude towards mainstream America and Vietnam. A significant percentage of Vietnamese American voters have favored the Republican party, evidenced by the long tradition of support for GOP candidates in local and national races.

The Heritage and Freedom Flag

On January 6, 2021, ultraconservative groups took siege of the United States Capitol in Washington, DC. The Capitol insurrection was a violent and unprecedented attack on the government, occurring during a joint session of Congress to certify the Electoral College results of the 2020 presidential election declaring Joe Biden the winner. Supporters of Donald Trump, who had refused to accept the election results and baselessly claimed voter fraud, stormed the Capitol and interrupted the congressional proceedings, temporarily halting the certification process. During the chaos, several individuals, including rioters and law enforcement officers, were killed or injured. The insurrection exposed the deep political divisions and raised serious questions about the state of democracy and the consequences of political leaders’ inflammatory rhetoric and rampant disinformation.

Image 19.05.01 — Ultraconservative groups take siege of the United States Capitol in Washington, DC, on January 6, 2021. A person prominently carries the flag of South Vietnam (center right).

Courtesy of Pacific Press, Getty Images. Metadata ↗

Among the flags raised at the Capitol alongside the Confederate flag and other symbols of white supremacy was the flag of South Vietnam. Yellow with three horizontal red stripes, this flag is a symbol recognized by some city and state governments as the “Heritage and Freedom” flag of Vietnamese American communities. Some witnesses were surprised by its appearance at the Capitol insurrection. Others, particularly second-generation Vietnamese Americans who have experienced the political expressions of their parents or grandparents, were upset at the appropriation of this symbol of their identity.

Why would a symbol of Vietnamese American freedom and heritage appear alongside symbols of hate in recent history? How do we approach the history of Vietnamese Americans with nuance and respect in the face of conflict and tension? As much as this moment revealed the political polarization of America, it also demonstrated the complexity of Vietnamese American politics.

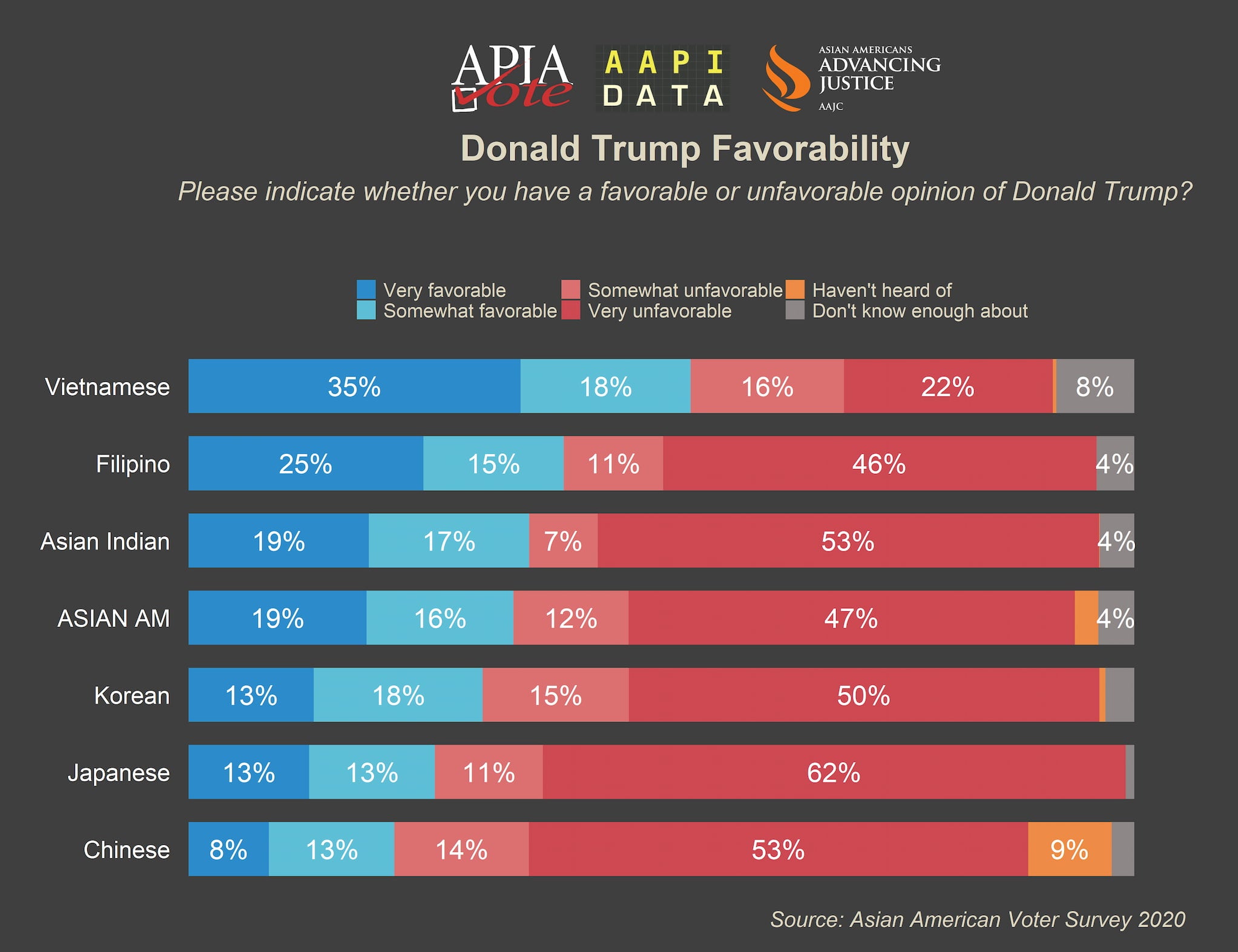

Image 19.05.02 — Infographic showing Asian American voters’ favorability of Donald Trump in 2020. This survey shows that compared to other Asian American groups, Vietnamese voters respond with a higher favorability to Donald Trump.

Courtesy of APIA Vote, AAPI Data, Asian Americans Advancing Justice. Metadata ↗

The South Vietnam flag, also called Cờ Vàng Ba Sọc Đỏ, has a bold yellow background with three horizontal red stripes across the center. These stripes represent the three distinct regions of Vietnam, connecting the geographically separated “yellow- skinned” Vietnamese by the same red blood.

The yellow flag originated in 1890 during the rule of Emperor Thành Thái of the Nguyễn dynasty, who is credited with abolishing the former flag with Chinese characters and designing this one for a new national identity. Over the years, the flag has gone through several design changes to suit the different political regimes. However, it resumed the original form from 1948 until the fall of South Vietnam in 1975, and continues to be deployed by overseas Vietnamese to this day to represent their cultural legacy, their commitment to the ideals of freedom, and the history of a nation no longer there.

Once Vietnam was reunified under the Socialist Republic after the war, the entire country adopted the red flag with yellow star, the symbol of North Vietnam since 1955. This flag, however, has been rejected by Vietnamese refugees, who argue that it symbolizes Vietnamese people’s suffering under Communism since 1975 and the new regime’s agenda of wiping out South Vietnamese history.

Among the diaspora, the yellow flag is burdened with moral, sentimental, and political meanings. It is the symbol over which debates about the meanings of the past are waged in service of present and future cultural and political goals. For Vietnamese refugee communities, the yellow flag has been at the forefront of public struggles over the writing of history, as well as over the terms of identity and belonging.

While the creation of the yellow flag under Emperor Thành Thái at the end of the nineteenth century signaled Vietnamese liberation from Chinese imperial rule, the yellow flag in diaspora has come to signal multiple objectives. These include preserving Vietnamese cultural identity, remembering the past, claiming both symbolic and geographical space, and opposition to the Communist regime based on their continued human rights infringements, and other values.

The new form of cultural nationalism among Vietnamese Americans often dismisses the yellow flag’s early history as a nationalist symbol uniting Vietnam against foreign rule and its northern colonizers. As much as proponents of the yellow flag wish to remember it as a symbol for freedom—in opposition to the red flag of the Communist government—the red flag has also unified the Vietnamese people against foreign rule just as the yellow flag did long ago.

Protest and Reckoning with the Past

Image 19.05.03 — Vietnamese American “Heritage and Freedom” Flag, flown at the city of Westminster Vietnam War Memorial.

Courtesy of Scarlet Sappho. Metadata ↗

Image 19.05.04 — Image of Hi-Tek protest by Ly Kien Truc.

Courtesy of UC Irvine Libraries, Southeast Asian Archive. Metadata ↗

A large-scale protest against Trần Trường, owner of Hi-Tek Video in Westminster, California began in January 1999, after he displayed a poster featuring the late Communist leader Hồ Chí Minh and the red flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in his shop window. Westminster is the seat of the largest Little Saigon in the world, and the incident took place around Tết, when the area was inundated with visitors celebrating the new year from near and far.

The two symbols sparked outrage among many members of the local Vietnamese American community, particularly those who had fled their homeland due to political persecution. They saw the display of Hồ Chí Minh and the red flag as an offensive and insensitive act, considering the painful history of the Vietnam-American War and its aftermath.

Protesters, consisting of community members and veterans, gathered outside Hi-Tek Video to express their anger and demand the removal of the controversial poster and flag. Demonstrations lasted nearly two months, gained media attention, and ignited heated debates about free speech and Vietnamese American history. The Hi-Tek protest raised important questions about the delicate balance between freedom of expression and the responsibility of community members to consider the impact of their actions on communities with traumatic refugee histories.

This event became a public stage for Vietnamese Americans of different religious, regional, generational, class, and even political backgrounds to engage in large-scale dialogue with each other and with public history. It also served as a space for negotiating community identity and belonging in the US. What occurred in the ephemeral space of the protest was an assertion of belonging by the Vietnamese community on a scale that had never been seen before in their “unofficial capital,” their stronghold in Orange County.

Remembrance and Moving Forward

As much as protests, demonstrations, and rallies open up public space for the negotiation of a group’s history, public art also helps preserve and reckon with collective memory and cultural heritage. A powerful way to represent a nation’s past and hopes for its futures, public art plays a crucial role for community members to engage with questions about identity. It allows us to remember and honor our past, acts as visual reminders of shared experiences and collective heritage, and fosters a sense of identity and continuity.

The perspectives communicated through public art might also challenge established, dominant narratives, and provoke critical thinking. By presenting alternative perspectives of historical events, public art encourages people to question the “official” accounts of history and engage in deeper discussions about the past.

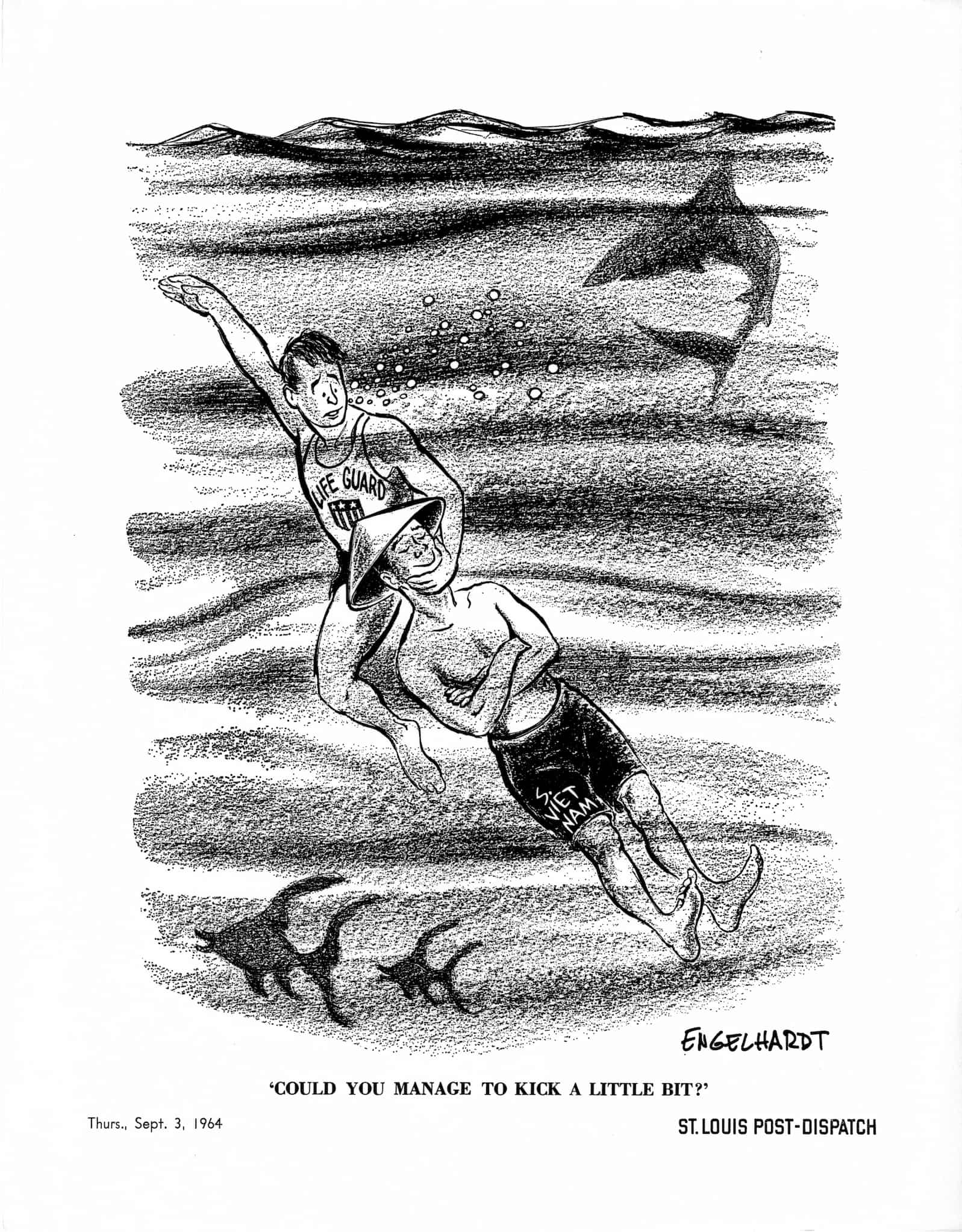

Scholars like Yến Lê Espiritu show how government and media narratives reduce Vietnamese refugees to just victims of war and objects of humanitarian rescue. For example, the cartoon below of a US lifeguard pulling a Vietnamese person from the ocean demonstrates this simplistic view of refugees. According to the cartoon, refugees do not contribute to their own rescue—this idea is part of a concept called “white saviorism.”

Image 19.05.06 — This political cartoon from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (c. 1964) demonstrates a simplistic view of Vietnamese refugees. The problematic depiction echoes government and media narratives from this time that perpetuate stereotypes of Vietnamese refugees as a burden to American society.

Courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri. Metadata ↗

In response to these narratives, scholars created a new academic field called critical refugee studies in order to paint a fuller picture of members of the Vietnamese diaspora. This field is interdisciplinary, combining traditional studies like literature, history, and sociology to help learners understand the complex processes of colonization, war, and displacement. Rather than seeing refugees as people who must always and only be grateful, critical refugee studies scholars like Espiritu recognize the context that brought Vietnamese Americans to the US in the first place. How we tell stories about the past matters for our identities today.

Nowadays, mainstream media tends to depict Vietnamese American communities as thriving, cohesive, and economically successful. These representations, however, often reinforce the “American Dream” and “model minority” narratives. Learning more about the nuances and complexities of Vietnamese American identity can help us push back on these simplified and harmful tropes.

For example, some Vietnamese Americans remain invested in being “good refugees,” a trope that insists they must be thankful for being rescued by the United States. Shortly after refugees arrived at Camp Pendleton in spring 1975, Vietnamese refugee Nguyen Luu Dat designed a public art monument that upholds this trope. Called Hand of Hope, the sculpture is of a giant white hand holding up two childlike figures. The monument sits on the Camp Pendleton Marine Corps base, and has been interpreted as an apt symbol for the concept of “white saviorism” by depicting an actual white hand saving Vietnamese people.

Because public art can powerfully and critically engage with history, Vietnamese American artists have often taken matters into their own hands to create representations by themselves, and for themselves. One contemporary example is a large sculpture entitled Of Two Lineages, designed by artist James Dinh. Standing in front of the iconic Asian Garden Mall in Westminster, California, the sculpture is a tall lantern-like structure that lights up Little Saigon at night like a beacon.

The lantern is surrounded by concrete benches with backrests made up of one hundred photographs of Vietnamese American faces. A reference to Vietnam’s mythical origin story of Âu Cơ, Lạc Long Quân, and their one hundred children, the sculpture incorporates the contemporary people of the diaspora. Of Two Lineages invites viewers to literally sit with community members and reflect on how the past intersects with our collective identity today.

Glossary terms in this module

Cold War Where it’s used

The decades (1950s-1980s) after World War II when the United States and its allies struggled against the Soviet Union and their allies for global power.

cultural nationalism Where it’s used

Ideas and practices related to a group’s efforts at cultural revival for a community that identifies with a national identity.

diaspora Where it’s used

The dispersal, movement, migration, or scattering of a people from their established or ancestral homeland.

reeducation camp (trại cải tạo) Where it’s used

Prison or hard labor camps under the Communist government of Vietnam where approximately 200,000 to 300,000 former South Vietnam military officers, government workers, and affiliates were sent for months to years following the Vietnam-American War.

refugee Where it’s used

A person who has been forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster.